Interview by Giulia Ottavia Frattini

An attentive interlinking of research, activism and art is what draws Caroline Sinders‘ eye and practice to the discussion and exposure of social dynamics whose contours are hard to discern but whose magnitude is widely tangible. Sinders adopts a journalistic approach aimed not merely at static documentation but rather at a willingness to disrupt the flux of facts and uncover them with an aesthetic choice that the public can give credibility to.

Her work may be regarded as an ongoing inquiry that does not sacrifice sensitivity and poetic intents while simultaneously critically confronting the audiences with the discomforting side of the events lingering and lurking in our lives.

The emphasis of her investigation hinges on the effect that technologies have on collectivity, how they infiltrate the processes on which it is founded and, more specifically, on the threats and harmful implications these convey.

The marginalisation of specific communities or sections of them, the concern for human rights, systemic abuse, right-wing extremism, digital harassment, surveillance, racism, misinformation and disinformation shaping Internet structures are the main areas discussed in Sinders’ latest project Architectures of Violence.

The intervention is an extended documentary exhibition – complemented by panels and writings – that urges the spectator to gain an increased understanding of how the online world we virtually inhabit is as actual as the physical one we walk through our bodies.

The viewer is prompted by a firm but not prescriptive hand to glimpse the latent entanglements between supposedly unrelated events. Architectures of Violence aspires to illustrate that the pernicious power of the Internet does not nestle in the shadowy corners of a remote cyber universe ruled by ungraspable mechanisms but in the very structures of its search engines and social media environments.

A foretaste of such an exploration can also be spotted in Sinders’ 2019 project entitled Higher Resolution. The show displayed interactive and collaborative artwork, talks by international experts and workshops to address power and privacy online – from the controversial theme of control to how AI is sculpting culture and human behaviour, touching upon the endangered challenges emerging technology can raise.

Intending to engage with different target strata and encourage the knowledge of a seemingly inaccessible world, Sinders, acting as designer, has also recently realised the exhibition Between systems and selves. Inside the venue were plexiglass sculptures that rendered malware and algorithms in plastic to make them more readable and palpable to human perception.

Therefore, from the researcher’s practice, it appears worth taking a stand towards an increasingly global and broad-scale perspective within the platforms we are constantly immersed in by placing diverse content moderators. The online space has the potential to transmit care, fluidity, and integration not as fictitious features but as a founding value of its unfolding. Wires can therefore become vectors of inclusion and move away from being weapons of subjugation.

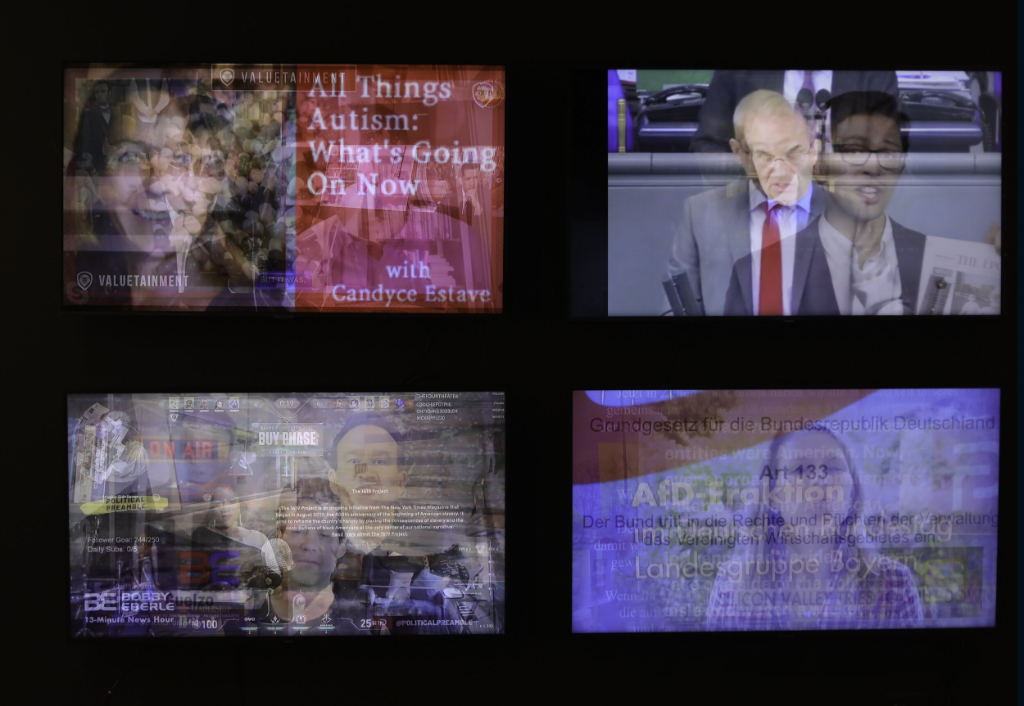

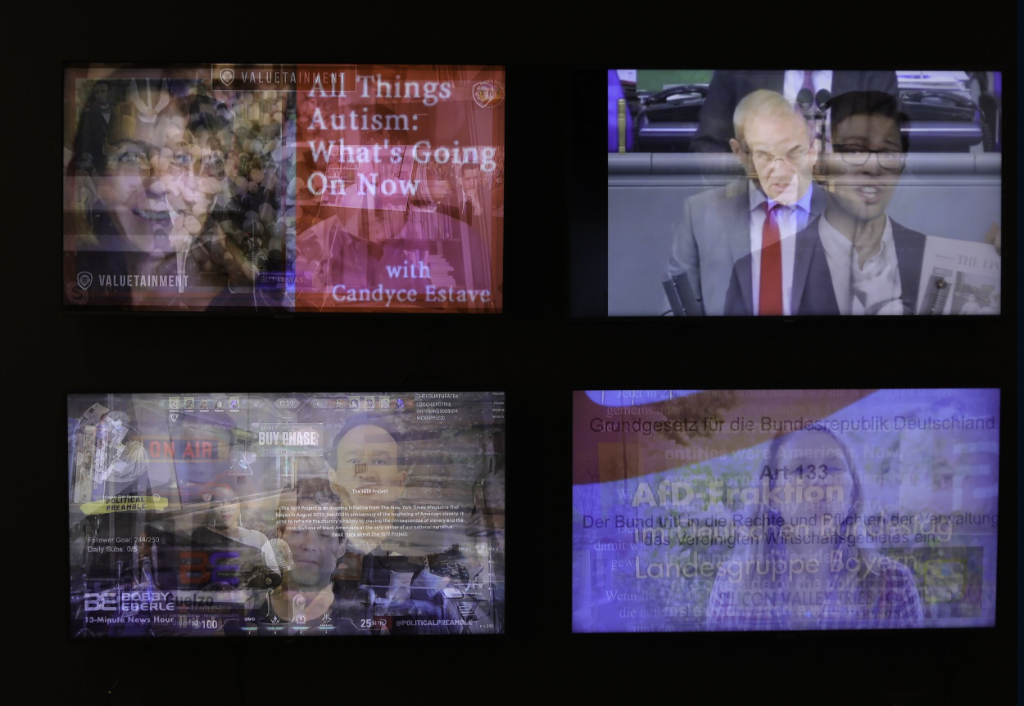

Right: Monument. Video still (2021)

I’ve read that your background has provided you with journalistic training. Do you think this approach is impartial, or does it somehow imply subjective vision is objective enough to trigger proactive awareness within a reality imbued with micro-stories and micro-personal truths?

Such a beautiful and profound question. I’m using photojournalism and my training as a former photojournalist as an aesthetic choice within image-making. And it implies personal visioning, in a way, but for me, it’s more, again, of this specific kind of aesthetic storytelling we see like photography has a truthiness to it. For example, photography for such a long time was considered more of a science. It had to fight to establish an artistic stance because image-making was seen as pure visual mimicry and as this objective medium.

So, I always find it interesting with photography the expectations or ideas we, the audience, have of photographs themselves, even though we know that they can be doctored. We are still sort of imbuing pictures with a kind of truthiness. I find that even more fascinating when we think of documentation and things like photojournalism when we think of news stories.

So this project is inspired by the construct of tabloid stories of news media of photojournalism, but in digital spaces and how that can be weaponised and how the certain visual hallmarks we have of truth and verification can be misused. In some of the videos in the show, when I was doing my research, a thing that came out was seeing how many YouTube videos use a newscaster-style aesthetic and set-up. For example, the kind of news show host on MSNBC, the BBC, or Al Jazeera.

And when I was doing this project, one of the things that I uncovered is seeing how the game show hosts from the 1960s have a similar aesthetic and that perhaps the newscaster aesthetic comes out of that game show host. So this aesthetic is weaponised by misinformation and disinformation channels on YouTube, almost as a way to peddle credibility to their false stories.

I’ve been researching digital harm since 2013, and I’ve read a lot of materials on how misinformation disinformation experts will coach journalists on how to talk about misinformation and disinformation content. So naming things but not linking to their same channels, or describing specific kinds of videos with a lot of detail but without connecting to the videos.

Whitney Phillips, the ethnographer of 4chan and the author of this is why we can’t have nice things, wrote in this research report for data and society called the oxygen of amplification- she noted that a few years ago on we believed that sunlight was a disinfectant that by showing these harmful things on the internet, we would help dissuade against it, and what, what ended up happening is we ended up uplifting it we ended up sort of giving oxygen to them, and even at times, increasing its popularity.

So, going back into this with the project within the terms and conditions, it’s the video pieces where all the videos are layered. I thought a lot about that. How can I sort of show and document what’s happening, but without necessarily constantly shining a light on this, so if you watch the videos at times, you can get some kind of more tell who the talking head is?

Still, you have to sit with them. You can’t immediately tell that. And one of the videos that are “within the terms and conditions” is a video from valuetainment. Valuetainment has this kind of high production talk show, MSNBC, cable news-style feel to it, you know, has intro music and these high fidelity high-resolution graphics, and it looks expensive.

One of the videos that I’ve included in the project. It’s this two-hour-long interview with Robert Kennedy Jr, Really espousing anti-vaccine rhetoric, with no pushback from the host, Patrick Bet David and Bet David gives Robert Kennedy Jr all this uncritical airtime. This entire is about two hours long. And it reads and feels like a grey area of support.

So it’s neither critical of the anti-Vax movement but also not outward or obvious support. And so, I’d argue this video is still supported by the lack of criticism and the length of the interview. However, it is in this grey area that I saw so much on YouTube.

And so, this project and my art show, Architecture of Violence, is sort of playing with the ‘aesthetics’ of media, reporting and ‘truthiness’ while also trying to report or document this content.

What does it mean to be an activist? And how in your artistic practice is his business inclination agency shaped?

It’s also an excellent question for me, as so much of my work is driven by research, activism, and art. So my current workflow is I start with research, then I move to activism, then I go to art, and some of that comes out of the fact that I am both a human rights researcher and an artist, but both of these domains are equally important to me.

So much of my recent work has been trying to show that I’m coming from a few different areas, like sitting on a council with the United Nations and advising on data governance and children. I also work with a citizen journalism group called Unicorn Riot.

I also provide security and emotional support to victims of online harassment. I also am looking at the effects of surveillance in my hometown of New Orleans. And then I also do all this, like, in my own quote-unquote spare time. But I see my activism very much linked to my research and my artwork because I start with practical research, and then I build off the research I’m doing into activism because activism is helpful. And then, art is like the last step because of art.

Art is necessary to me because I want to do research that includes data, and I find it practical because it creates something that wasn’t there before. It tests a hypothesis, and sees if it works or doesn’t. Still, activism is built off practical research, and activism is helpful because it pushes society forward in the ways it needs to be pushed, and then I take actors and research.

Then, finally, I distil it into something else, which can be art or critical design, because I think that that’s a kind of poetry, that is necessary to help the world function and helps create new imaginaries, and it does it in a way, sometimes that we can’t just do with activism. Activism can provide the basis for those imaginaries, but then art can help coalesce and create that.

I think for me, what it means to be an activist sort of means also really responding to current urgencies and removing my ego from it and working with communities, so I have seen a fair amount of artwork that is in response to current speeds or takes perhaps an initial activist stance but doesn’t seem to be working with either the communities who are or who have been doing that activist work for so much longer or also the advocacy groups that are working with communities. I see them all linked.

To be an artist and activist, we have to be working with others, and frequently that means doing something like it often implies working at the group’s speed and creating what the group needs, not what we think they need. For example, I think a PDF is compelling, meaning if you go in and you’re interested in a topic. You’re working with a community.

You have to move at the speed of that community, and sometimes what they need is not a new tool. Sometimes what they need is just help phone calling people, like being a phone bank, or helping organise a PDF or sorting stuff into boxes, and I think that’s extraordinarily powerful.

What do you see as the most significant challenges in acknowledging that our lives are effectively experienced online as offline, and most importantly, that one directly impacts the other?

I mean, also, these are all great questions. To answer this, I’m going to have to be specific again in this particular slice of what I focus on, which is online harassment. One of the biggest challenges is getting people to realise how invasive and harmful harassment feels because I think there’s this kind of a common misnomer that online harassment is just one person saying something negative about you and that the people, the victims.

Then are just not quote-unquote like strong enough, and that’s not true, because it feels so invasive if someone comes up behind you and shouts in your face right or whispered something in your ear, and it feels that invasive online.

And that to me is one of the most significant challenges is saying, well, just because it’s said online that doesn’t mean it’s any less harmful doesn’t mean it’s any less problematic for whatever reason it seems more challenging to get people to realise that until they’ve experienced online harassment.

What use do you make of your social media channels?

I like to struggle with social media because I don’t necessarily know how to use it well Twitter is a space for me to see breaking news and engage with other researchers and artists. You know they’re not my immediate community. It’s a way for me to keep in contact with, you know, my friends who are not immediately around me and the same with Instagram.

Still, I feel like I don’t use them very well as an artist, or I’m not very good at self-promotion on them, and that’s something I, I struggle with, but I also then like the way I use social media because I’m using it just sort of for me.

Sometimes, it seems that we can totally recognise the harmful mechanisms operating beyond the screens and in the digital platforms we constantly attend. Nevertheless, it feels as if there is a tacit agreement between the users, the agendas of these structures and their troubling effects. What are your thoughts on this? And specifically, how could a project such as Architectures of Violence contribute to this disrupted dynamic?

I think we, at times, recognise the harmful mechanisms, but that doesn’t mean we have. That doesn’t mean we have agency in choosing to engage with them or not, but instead that the power that a platform holds is so much bigger than us as individuals.

But, then I will say that pushback against platforms is super significant because it causes it does cause them to change along with regulations like activism investigative journalism and regulation against platforms; all are all interlocking things, you know, it’s not just like to have the regulation, you need the investigative journalism, you need the public outcry, you need the public pushback right. Hence, it’s not like one or the other you need all of them together.

And so I feel like there is this quote-unquote tacit agreement, but I also feel like it’s an agreement that we kind of can’t opt out of. For example, years ago, when I was applying for tech jobs, every job application asked for social media handles.

But beyond that, we have to acknowledge that in some cases, to stay contact with friends or family, you have to be on a platform (including WhatsApp, Telegram, etc.). Additionally, I think we forget that Facebook has an entire program called Facebook Basics in the Western world, and that’s how people access the internet.

There are so many nuanced problems to this. I hope with architectures of violence, it more drills down for white people, in particular, that the internet, the big platforms they/we are, which is called the clear net- that there’s way more harm and violence on there than we, white people, realise because we’re not receiving it.

So one of the ways I’ve also described this project is I really want to make white people uncomfortable around digital violence, and that it’s violence, sometimes they do not receive, they don’t see it unless they think it’s not there, and it is there. It’s there on our clear net. And so this was like a whole series of projects sort of exploring that idea and thinking, well, how do I do a project that feels representative of what’s happening right now on the internet with all of this harm?

So it is partially revealing and is partially trying to talk about these structures, and I also mean even the name architectures of violence, as I want people to realise that the internet is built. It is a built thing that is as built as the building or room you’re in or the chair you’re sitting on. It’s not random. I like to say that every bug is a feature until you fix it, meaning every piece of code is written. Everything that’s happening on there, there’s a decision behind it.

What do you consider the immediate urgency in our present time that should be tackled on a political, social, and cultural level? According to which criteria did you gather the materials displayed in Architectures of Violence, and which events did you mainly dedicate attention to?

I would say to answer this question, and maybe there needs to be a follow-up question we can have about the solutions, of which there are so many current urgencies and related solutions. But, one of the most immediate urgencies is this amount of harm online. And the problem isn’t just the harm people are facing and seeing; it’s also the harm that content moderators see in trying to moderate this content.

It is so thorny and so complex and complicated, but this is a current issue. And the solutions to it are also adamant. There has to be an intersectional and global focus on these solutions to mitigate harm and then unintentional harm rendered from any potential solution.

For example, online gender-based violence frequently will call for much stricter guidelines of content and more stringent content takedowns- with which I agree. Still, we have to think about how that is enacted at scale via platforms, how platforms mess up this stricter enforcement, and that can lead to censorship, particularly of non-western audiences.

Why is that? Well, platforms often don’t have content moderators working across all different languages. You don’t necessarily have teams in every country, and they don’t tend to understand that geopolitical events are unfolding on a global scale. Platforms understand the Western world and sometimes Western harms- and so when we call for more stringent measures.

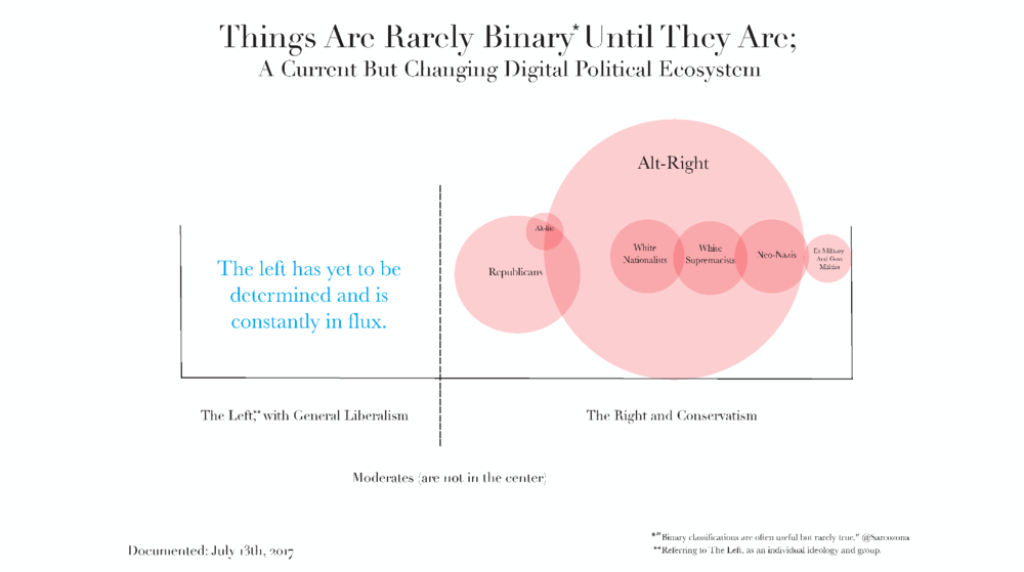

We also have to recognise their downstream effects, which is why I mean where it’s so thorny. For me, that’s why I focused a bit on white supremacy and why I did focus on Western actors within that space. These harmful actors I was researching- the people who speak English, speak German or French or speak various languages found within the EU and North America.

And there are so many people employed by these platforms across the EU and North America. Yet, we still have problems with white supremacy content online, even with human rights groups and watchdog groups. Advocacy groups monitor hate speech groups and write reports in English about these hate groups. Yet,- we still have hate groups’ videos online, and they have accounts on these platforms- why is that? That, to me, is one immediate urgency across many, many urgencies.

What are you unafraid of?

I’m not afraid of the future, even though I don’t know if that sounds like a throwaway question. On the contrary, I’m excited to see what the future holds. And I think, in a way, as a survival mechanism, I have to be hopeful for the future.

Otherwise, I don’t know how I could do the work that I do. But I think it’s also because I know so many brilliant people that are constantly working in public and private, with many people not even knowing who they are- they are working to make the world better. They do important and urgent work. And so that makes me feel hopeful. When I see my colleagues and comrades working, and so I am unafraid of the future.

What is more important: to take or not to take yourself too seriously in order to be creative?

I mean, this is such a tricky question for me because, on the one hand, I wish I could be a little more humorous and then, on the other hand, I’ve definitely seen art pieces that are trying to use humour to address inequity or violence, and then really failing to do that- and potentially becoming harmful themselves.

You need the right amount of seriousness, and I think you need the right amount of humour and levity, and I believe it is contextual. But, still, I would say in this project that I had to be super, super serious and very, very careful in this project one, not accidentally to platform or uplift these groups. And so I had to be, you know, as detailed as like a surgeon’s scalpel in a way, but I think there are other projects in which you can be unserious and have an impact and still be focusing on activism. And I think that that’s also really important.