Interview by Silvia Iacovcich

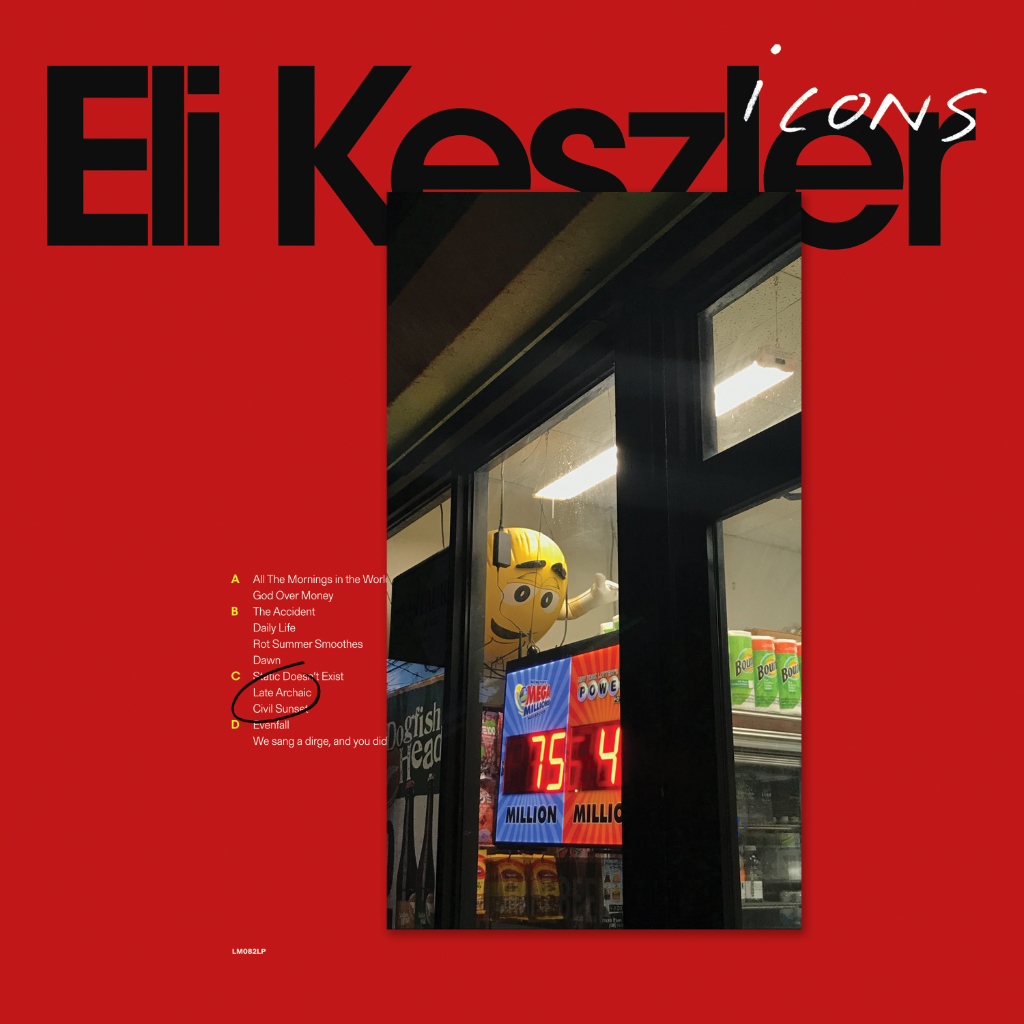

Experimental percussionist, composer and visual artist Eli Keszler challenges the reminiscence of the past two years through his latest project, Icons, out now via Lucky Me. As we quickly try to come back to what once was, Keszler’s album explores the varicoloured scenery we have been navigating during the pandemic and the anatomy of lockdowns, inspecting and dissecting each fragile microcosm and hours that have been shaping 2020.

Cradling the listener into a familiar world made of slightly altered sounds, mixed feelings and soundscapes, the tracks spiral into a picturesque, dystopian, political day in a life. We are presented with an unstable reality made of silence, protests, ambulances and children’s chants, held into a distorted collage nourished by NYC Jazz, electro-acoustic, ambient landscapes and ancient scales that keep it thick.

The album’s atmosphere is deflated and lonely: Keszler’s wandering around the Big Apple records abstract and delicate layers of sound that prompt a deep listening into the stillness of the inaction – intrinsically peaceful, addictive, and sublime.

Icons don’t reconcile with the sophisticated drumming Keszler is well known for or the combination of punk rock, free jazz and improvisation his previous albums recreated. Stadium, his 2018 work that awarded him the Bookmat’s Album Of The Year, navigated the same Manhattan in an opposite latitude by exploring its plasticity and resilience of ordinary life. Keszler’s approach to the world is perceived through sound but always integrates distant, inner adventures as they shape around the conjunction of the five senses.

Meshing visions from metaphysical themes in Russian filmmaking, politics, deserted metropolis, diagrams and drawings he takes himself, his projects end up being timeless through a combination of elements that harmonically fit in each of his elaborate landscapes. Through primitive instruments and raw, archaic materials like wood, metal, and water, we can get back to our foundation.

His sound installations naturally reach the public, intermixing collaborations of different shapes and forms, often involving mechanisms to transform the urban scenery into more than a view. For example, in Archway (2012), a set of piano wires were mounted up to 800 feet long off the Manhattan Bridge, making the piece of architecture the ultimate performing element, an instrument and part of a set of liberating hypnotic melodies created in synergy within the environment.

Keszler always creates a balanced field where improvisation and rehearsal combine effortlessly; the space left between composition and performance subtly softens, taking new, unexpected forms. And that’s the beauty of his stuff – sometimes you hear it, sometimes you see it, and sometimes you can even become part of it.

It’s not surprising that his installations have been travelling around. During the past few years, his ability to convey images into music found its way into score composition, contributing to The Uncut Gems Daniel Lopatin’s soundtrack and The Scary Of Sixty-First, for which the composer wrote the original score.

Working across music, film and art, how has your sound developed, and what have been the main sources of inspiration or significant data influencing your work, from R.L.K. to Icons – maybe before 2007 as well?

I’m always checking in on my friends, the world around me, politics and culture. The context I find myself in is probably my largest single point of influence. I always think about how, where and when an audience will receive something. That’s the central influence on my work, and if I follow that really closely and precisely, I feel things come together quite naturally.

The concept of Icons focuses on travelling and its loss/renewed identity during the past “hectic but very still” year: what were your main compositional and production challenges through a journey that seems to split in between your esoteric memory and the field recordings recorded in a misanthropic New York, so consistently different from the concept and the idea of the urban landscape that transpires from Stadium?

Icons is a somewhat removed, surrealistic internal world of music. I was imagining landscapes and spaces in my mind and trying to reflect on the feeling of the last year as we move forward, asking what that might mean. I wanted to create something quite beautiful and psychological, almost hazy with its internality. Stadium was a fictional world in the sense of being about an imagined New York and pairing this with the more plastic reality of contemporary metropolises.

Icons is impregnated with silvery and delicate sounds as if the listener was pushed into making an effort to reach a deeper perspective that would be inaudible or misinterpreted if shot on a higher scale – it feels pretty allegorical of an inward reflection that positively resolves to integrate hyper realities and perspectives through fresh connectivity. What was your intention when you were traversing the empty Manhattan, recording soundscapes?

That’s exactly right. Walking around the city and recording was a shocking and beautiful experience. It’s hard to describe how strange it felt, the stillness of a city that is normally in constant motion. I was thinking of Tarkovsky, Kitano and, Romero, many other directors that have worked with this type of emptiness or stillness in their films and what it could mean in music. At the same time, I wanted to make something delicate and beautiful because I didn’t feel that it was ugly or even sad exactly, just startling and shocking in its stillness.

Your sound is imbued with steady combinations of avant-garde, industrial and ancient scales – what’s the relationship between past and future to you and to your music, and how does technology fit in this expanding landscape?

I have always wanted to make music that could exist across any time in history. If the power grid collapsed, I could play nearly the same music as with it on. I don’t want to rely on or box myself in by contemporary standards or trends that are fleeting and always replaced. That’s why I like to work with raw materials and traditional instruments – wood, metal, water etc. – these materials are deeply rooted in our unconscious.

In my mind, I’m in dialogue with the whole history of music, not just my contemporaries. I always keep that in mind when making music. Having said all that, I’m interested in technology, of course, and try and use new techniques available to me.

Your interaction between sound and environment is one of a kind, equalising physical and virtual spaces in your performances, recordings, and installations. How do you work on achieving this fine line where a musician can become a piece of art? The urban environment goes beyond its structure and becomes an integrated part of a piece, very naturally but tensely; what comes first in this synergy, the eye or the ear?

I wouldn’t say musicians are necessarily art in themselves, but music can be. I have eclectic taste and don’t place one category of creative expression over another at face value. This is quite a simple idea, but it’s been incredibly liberating – all of a sudden, the whole world opens up to you. I’ve tried to work from that place. On the same note, I listen to and experience music with my whole body and view art in the same way. I’m unconvinced that we can separate our senses, and I instinctively feel over time, we will learn this to be more true than we thought.

Your collaborations are prominent and assorted: Spencer Yeh, Loren Connors, the Icelandic Symphony Orchestra, Skrillex, to name a few. How do you work on the conceptual side of your collaborative projects, particularly in relation to your experience working on the soundtrack of The Uncut Gems or The Scary Of Sixty First – film scores, ‘fabricated’ environments?

I approach it as all the same, to be honest. I look at the music, film, or space and try to take it in and then respond to it instinctively. If I stay out of the way of this process, I find things work out really well. A physical space or a film, a record etc., are just different types of locations to work from.

What’s the chief enemy of creativity?

Negativity.

You couldn’t live without…

Creative manifestation.