Interview by Laura Cabiscol

Patricia Dominguez is an artist, educator and activist from Chile whose work merges socio-political and economic matters with mysticism and ancient botanical knowledge. She is also the founder of Studio Vegetalista, which has existed for more than 10 years serving as a platform for producing experimental ethnobotanical knowledge and research through interdisciplinary practice that combines art, ethnobotany, and healing cosmologies.

Studio Vegetalista is the crystallisation of the artist´s individual journey; after studying for a certificate in botanical and scientific illustration at the Botanical Garden in New York and working in the palaeontology department of the Museum of Natural History, she reached a point where the scientific approach to studying and understanding plants was falling short for her.

It leaves little room for imagination and experimentation, and it has a complicated colonial base as it originated to document knowledge about plants to be renamed, classified, and exploited for their possibilities of generating profit from a Western point of view, disregarding and undermining previously existing indigenous knowledge. Together with collaborators and peers, Dominguez has developed a school, publications, interviews and experimental essays around the current relationship between humans and plants.

She approaches art as a field of possibility, understanding how it can disrupt predominating narratives, challenging established interpretations and imagining new ways of approaching the issues we face as a society. Her work is very much connected to her activism. It takes on different manifestations, from print publications to video works, sculptures and workshops that try to analyze, understand and represent the complexity of these relationships in the 21st century.

Rich in symbolism, her work invokes the ideas she explores through totem-like figures, connecting to a practice human beings have done since immemorial times (think, for example, about Paleolithic paintings like the bison of Altamira). Symbols can also be used by one culture to dominate or overpower other cultures, as it happens in our globalized world where the mainstream imaginary is completely Westernized. Dominguez’s work is infused with indigenous symbolism while incorporating elements of global culture and new digital aesthetics.

For example, the interactive publication GaiaGuardianxs (2020) is the culmination of three years of research and the artist’s personal journey through water-related conflicts in Latin America. Much like most of her works, it’s very sensitive to the post-colonial extractivist policies affecting the land and seeks to reflect the existing frictions between the oppressor and the oppressed.

She is currently conducting research at CERN, taking part in the second edition of the Simetria residency. This program promotes exchange and collaboration between artists and scientists from Chile and Switzerland. As well as CERN and as part of the Simetria program, she will also stay at two astronomical observatories in Chile, together with Swiss artist Chloé Delarue: ALMA (Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array) and the Paranal Observatory. In this interview, she delves into the motivations and meanings behind one of her latest projects, Madre Drone (2020).

Tell us a bit about Ethnobotany as a discipline, how you have incorporated experimental research in ethnobotany in your practice, and what role it plays in your way of seeing the world.

Ethnobotany is interesting to me as a discipline, but it has its limitations and its colonial origins since its focus is often placed on economic relations or on analyzing the gaze of an “other” or an appropriation of ancestral knowledge, identifying resources to extract.

In addition to being a visual artist, I have a background as a botanical and natural science illustrator. I studied at the New York Botanical Garden and worked in the department of the American Museum of Natural History. There I reached a rational wall and was able to see the limitations of the scientific gaze. I still respect it immensely, I even teach scientific illustration at the university, but I am very aware of its limitations. So this updating of the representation of plants that I propose in my work comes from a critical twist within the scientific language.

For me, plants are a source of knowledge rather than subjects to be studied. They are powerful terrestrial technologies with the capacity to be allies of humans in the processes of change we are going through. Plants can give us vision, reset us, cleanse us, heal us, guide us, challenge us, and accompany us in our contemporary rites of passage. That is why I approach ethnobotany in a sacred, emotional, experiential way.

What interests me are the current or futurable relationships between humans and plants. I am interested in finding new ways to represent and speculate with the plant world in this technological age and in the context of the cyborg qualities we are incorporating into our holograms.

These days I consider myself a student of the language of plants. As Eduardo Kohn says, forests speak through images, like dreams. They have a complex non-verbal language with multiple layers and temporalities. This is why I think we have to let go of science and jump into the void of the perception of the Vegetal Matrix.

Tell us how Madre Drone came to be, as it seems like it was a very organic process and ongoing for a while. How did it start and evolve through time? Did you have a clear concept, idea and storyline from the beginning, or was it taking shape as you went, etc.?

Madre Drone examines the complex flows of water as a function of the possibilities of crying, environmental and social crisis, healing and spirituality in the digital age. Waters, vapours, terrible thirsts, tears.

Madre Drone was made along the way. At the end of 2019, I was caught by the apocalypse with a camera in hand. I navigated a series of events that began with the Bolivian Amazon fire in 2019, followed by the civic strike in Bolivia because of the electoral fraud of Evo Morales, and then I jumped to the Social Outbreak in Chile. During the same month, the fires symbolically jumped from Chiquitanía to Ecuador and Santiago, leaving animals and blind people in their wake. In this journey through the deep social, environmental, human and multi-species crises, my way of digesting them was through this video and publication.

As I was in Bolivia doing a residency at that time, I changed my plans and ended up taking care of animals affected by the fires. One day, I had to take care of a toucan that was partially blind. While I was at the shelter taking care of him, I wrote the following:

“Quiet, the blind toucan felt me with his right side. It also looked at me from time to time with its left side. It is a mystical mask, a mythological animal that has emerged from the fire of the Chiquitanía and the Amazon. He has two faces; they have burned his right side, the masculine side, the side that capitalism requires of all of us. By losing his eye, he has been transformed into one of the seeing machines, into monsters that see beyond the visible”.

After the residency and being caught in the civil strike with no food, cash or mobility, I returned to Chile and jumped into the social outbreak where more than 407 people suffered eye injuries from police repression. This blindness narrative started emerging, where the eyes of a toucan blinded by the fires were the witnesses of a bastard reality crossed by a thousand stories, and the eyes of a blinded human were the brutal consequences of the social protests in Chile in 2019.

In the video, the eyes of the toucan and the human eyes cry together in a South American cosmic cry. A myth in which drones weep, where blinded toucans can no longer see fire and where young humans protesting for dignity are forced to transcend the visible for the invisible, for a new vision, in every sense. They become a kind of amulets that try to capture the spirit of the contemporary.

You also feature images that not only you shot but other people (such as those from the revolts in Chile). How did those collaborations come to be?

I have been working for some years with Pamela Cañoles and Emilia Martin, artists working in film, audiovisual and experimental sound production. Throughout the videos we have made together, we have developed a creative relationship of trust, friendship and a deep understanding of our artistic endeavours, visions and ideas behind our respective works.

When the social revolt exploded in Chile, I was locked in the Kiosko residence because of the civic strike due to the crisis caused by the fraud in the elections of Evo Morales in Bolivia. I had just finished a month of filming Madre Drone. On the last night of filming, we had to finish earlier because the civic blockade began, and we could not continue working.

That same week, in the images coming from Chile, many laser pointers appeared in the protests, influenced by the recent protests in Hong Kong. Lasers were being used as community ‘light weapons’ against police repression. Many lasers together, focused on a tank or drone, are capable of momentarily blinding us and giving them time to escape. Using the blinding potential of laser pointers, they spontaneously brought all their light beams together, and all aiming at a spy drone at the same time, they shot it down. The social struggle was transferred to the air, using the transparency of light as a weapon.

Emilia and Pama live very close to Ground Zero, the epicentre of the protests. They started documenting the revolt from the beginning. So, I asked them if they could shoot a few days of footage for my video, with a focus on the laser lights; some abstract images of the green laser pointers, so I could connect them with the lasers I had used in Bolivia in the video I was shooting. These green lights were the visual way I found to weave together and choreograph the deep social and environmental crises we were living through during those months (and that continue to happen until this date).

Part of the communal energy of the social outburst has been based on collaboration, so it is significant that this video was shot among several hands. On the other hand, at that time, I had a production budget that I had been given from CentroCentro in Madrid for the exhibition I was preparing, so it was nice to share it with my friends who collaborated on the video in times when work was scarce, and everything was half paralyzed.

Madre Drone is full of symbolism. Take us through some of the most important symbols in it and what they mean to you. (The boy, the fox, the toucan, the drones, the robotic figure at the end…)

Yes, I see the symbols in the video as technologies for encoding information and experiences that reach the viewer through emotion. A symbol is when an event has given a second meaning to an object. It is an element of the tangible world that has been trans-signified by an event or person. The expression of the mystery or the immeasurable must be through the symbol since it is something analytically immeasurable. Let´s go on a journey through each one.

The carer in charge of the toucan was Darwin, a 17-year-old youth who worked at the sanctuary. He was the one who received the last links in the Darwinian chain, where the strongest survived. He received the burned, dead, dehydrated animals.

One day, we received a dead fox. He died of dehydration on the way to the animal shelter. Its body was a scapegoat, a sacrificial. And who deals with the body? Darwin. Who buried him? Who returned it to the earth? Darwin. What to do with his grief? Does he offer it to the earth, to the coca leaf, to his motorcycle, to his smartphone? You’re a silent hero, Darwin! Armed with a cellphone that thumps out reggaeton and your perfume of fire.

Although the word “guardian of the earth” is problematic because of the idealization and romanticization of the people that defend and take care of the land, I wanted to portray him as a guardian who exudes green. A true guardian of that forest. A servant of that forest.

I took a photo of him next to ‘Maléfico’, (‘the Evil One’), a green parrot. The green exuded by their bodies remained captured in the image. Green, the colour that keeps us sane. Darwin and the Evil One. What a couple! They make me think about the theory of species and the survival of the fittest. These burnt animals are the last links in the chain of creatures affected by fires. Darwin’s fucking theory. There’s nothing left now but their burnt skins.

Those charred skins cover wild spirits expelled from their forest by the fire. Sick and burnt in their new cages, they are still beings with free spirits. After the fire, they are in the first phase of domestication. There is no turning back, and they can no longer survive without humans. Witnessing their indomitable and feral impulses inside their cages was an experience I am still unable to put into words.

And the next day, we received several toucans. Some had burned wings or legs. One had lost its sight and was very disoriented. At noon it was time to move the toucans to their provisional new cages. I was asked to hold the blind toucan and put a cap over it so that it would not escape. I placed my hands on it carefully and felt it quiver through and through with fright. Its whole body was shuddering under my protective grip.

Toucoutoum toucoutoum toucoutoum.

Toucoutoum toucoutoum toucoutoum.

Toucoutoum toucoutoum toucoutoum.

I closed my eyes and connected with it. Toucoutoum toucoutoum toucoutoum. We palpitated together, the bird in its terror and me in my attempt to contain it. We were synchronised for a few seconds. I could feel the beating of everything alive through that bird, the palpitation of the earth.

Looking after the blind toucan was my way of touching the spirit of the forest. I felt scanned by the bird. When I brushed one of its feathers, I was vertiginously connected with the immensity of the vegetation.

One month after that experience, In the context of the protests in Chile, I heard the buzzing of police drones spying on activists. Dzzzdzzzzdzzzz, dzzzdzzzzdzzzz. I’ve seen those unmanned crafts with my own eyes flying down into the inner courtyards of buildings, looking for faces, spying on assemblies, hovering over the protests, filming and indexing guilty parties through its pixelated vision. Dzzzdzzzzdzzzz.

I define a drone as an “astral extension” of a human being that allows them to move across the world above. A flying eye. A vigilant eye. An eye suspended in the air. They are the new power animals, representing this new era of vigilance and control.

I raise my eyes towards the sky full of green lights pointing at the drone. I feel the presence of the toucan flying around it in circles as it falls. I ask these blind birds to activate my vision of the invisible. An era of police astral flights is dawning. Their visions, enhanced. The drone, the watchful eye of this era, is destined to be brought down by the collective.

Laser bird, do a scan on us.

Activate our weapons of light.

I wrap myself in green to exude forest, to palpitate with living.

I endure.

Our suns fall in a scroll down,

Updating the fire holograms.

The robotic figure at the end brings an outdated image of the future. One of the main questions I ask myself nowadays is what kind of technology we ultimately connect with and what is the true meaning of connection these days. In Madre Drone, the outdated image of the robot symbolizes the idea of blindly follow to the future and gets replaced by the communal forces of the protest of refusal. Maybe that’s a non-mainstream vision of the future too? A vision where we learn to use our biological technologies more than depending on the flow of information coming on our technological devices.

Some people have told me that the blind toucan has visited them in their dreams. Another person told me that he cried with his male eye (the right one) when seeing the video. These kinds of events are interesting for me, as they confirm that certain symbols transcend my personal experience and have a life of their own, being ambassadors of these multispecies resistance myths I’m portraying in the video.

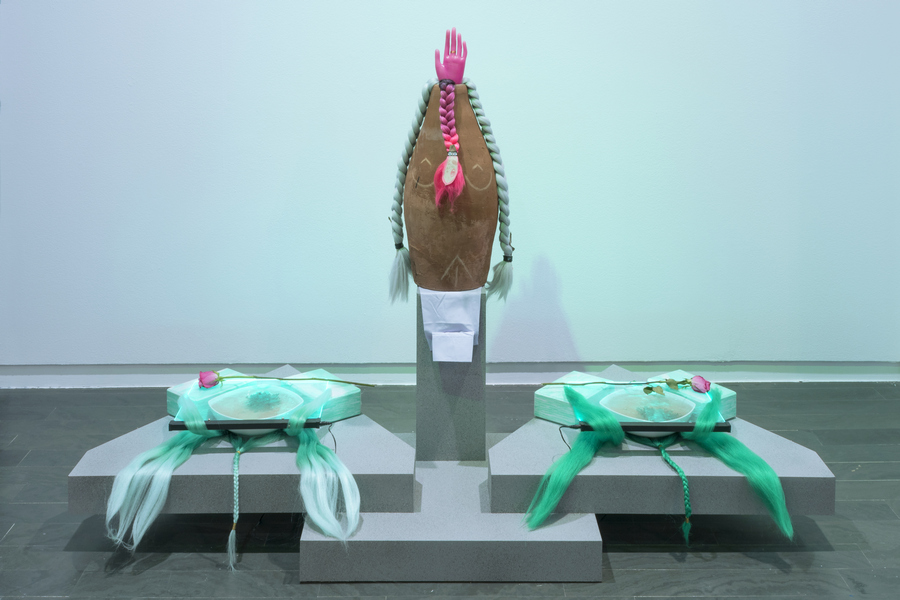

What were the two altars in the Transmediale installation representing, were they meant to be a space to pay tribute to the animals lost in the fires and to the people fighting for their rights?

What moves in the spiritual world needs its double in the physical world, so every object on the altar means something and has an internal logic. That’s how altars can be portals to connect with certain events and energies that are being invocated. We need connectors from the invisible energies to the tangible world. The configuration of the objects of the altars moves and reorganizes those invisible energies.

The altar we set up at the Transmediale was an altar to honour vision. Physical vision and metaphorical vision. That vision that we are acquiring to expand our paradigms, our cosmologies, and our outdated systems.

I decided to make a sculpture to honour the eyes wounded by police repression and another for the wounded eyes of the blinded toucan. Through these meta-eyes that cry, we can symbolically access all the other human beings or animals that have been assaulted, mutilated, abused, and burned. I see the sculptures as gateways. And these gateways had vegetal offerings of medicinal plants and also round stones presented in multispecies hands in order to symbolize the lost eyes.

These offerings appeal to our quantum existence. An intentional offering in Berlin for a person who lost his or her eyes in Chile can perhaps be felt in some invisible way by the person. The quantum field, like the spiritual, has no physical distances.

Madre Drone has a very Sci-Fi feel. Is that something you are into? What are some of your literary and visual references, both for this project in particular but also in general?

My visual references come mainly from things I see in this territory. For example, the ancestral masks of the festival of La Tirana with their LED lights, the light of our cell phones shining on our faces at night, knowing that we have the same silice as the quartz chips in the centers of our smartphones. Pre-Columbian thought, the futuristic myths of the Pachakuti by instance.

Although my work looks sci-fi, the wells from which I drink really come from the street and its markets of cheap objects that look like they were just downloaded from the internet or from the spiritual information that we investigate in the different study groups I participate in, or from dreams. And a lot of the internet as well.

Chris Marker’s Jetée is one of my great inspirations in relation to sci-fi. Also, the ancient pre-Columbian Mayan and Diaguita representations of their technologies of connection. Octavia Butler’s writing. The inquiries of Carlos Castañeda’s reveries and Marisol Hume’s Oniro Navigation techniques. Marosa di Giorgio’s shape-shifting writing in La Flor de Lis. Mount Analogue by René Daumal.

Although I don’t feel very identified with science fiction, I do believe that fiction is crucial. Fiction has to be needed, as artist Walid Raad told me one day when I had a studio visit with him in 2013. We are used to accessing information in the same ways, and the ways of access seem to be standardized. From fiction, we can imagine other possible ways of accessing reality, imagine other ways of reorganising the present and projecting what is to come.

I’m interested in multi-species science fiction, a spiritual one, not one of conquest or domination. An organic science fiction. That’s the ultimate sci-fi utopia for me. To learn how to use our organic

What is your chief enemy of creativity?

My chief enemies of creativity are 1. fear and 2. lack of epic-quantum thinking.

You couldn’t live without…

My multispecies allies and friends.