Interview by Ana Prendes

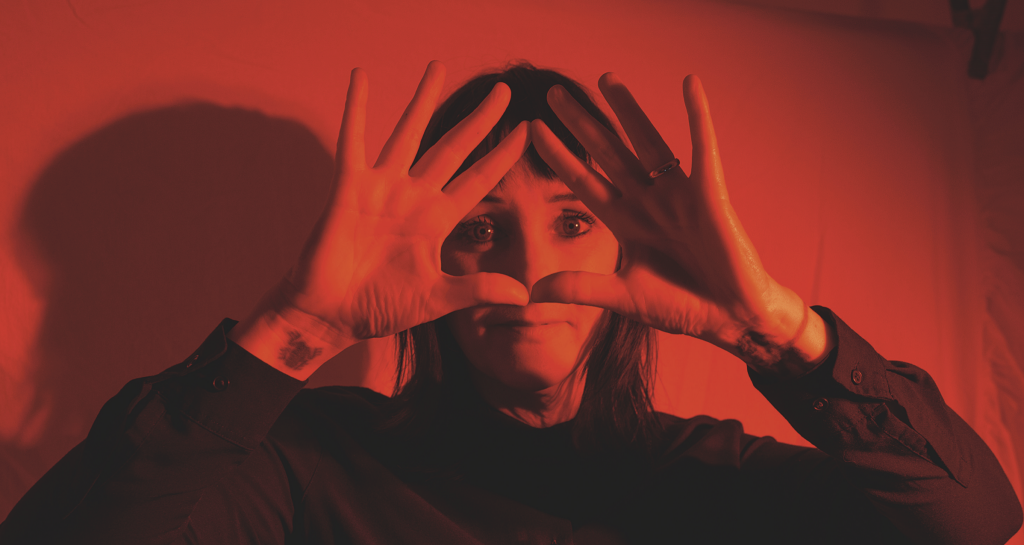

For over thirty years, British artist Vicki Bennett – aka People Like Us – has been radically approaching audiovisual collage. Self-described as a redirector and decomposer, Bennett samples, edits, and merges audio and video footage from popular culture, constructing unexpected interconnectedness between characters, landscapes, and sounds.

With repeated viewing and twisted humour, her films are a sensory overload that unfolds into unbounded and non-linear narratives. This approach creates an individual journey for each viewer in the audience, subject to their particular reactions to the pieces of video and music they recognise and their built-in memories. Bennet goes beyond recontextualising pop culture or bringing back nostalgia, but she aims, in her own words, to ‘make experiences psychedelic, to create and reflect magic and wonderment.’

Starting when access to computers was nowhere widely available, Bennet’s process shifted gradually parallel to technological development. From collecting local and physical footage materials in the 90s, the change of the century allowed her to make use of affordable high-speed computing, file-sharing platforms, and editing software as they became accessible. On top of this development of her methodological approach, the transition from limited to the abundance of resources challenged her creative process, learning ‘how to adjust one’s focus not to be overwhelmed.’

Bennet is speaking after the premiere of her latest feature film, Gone Gone Beyond, at the Barbican Centre (London, UK), her first work that exceeds the one or multiple-screen cinematic display from previous projects. It uses Naut Humon’s structure CineChamber – a ten-screen, eight-speaker space that creates a 360-degree audiovisual experience for an audience located at the centre of the room, dispersing perspectives and possible points of view.

Without intending to reveal many details for those who have not experienced it yet, Gone Gone Beyond’s opening – a surrounding landscape of dozens of candles in a darkened room – feels like entering into a meditative state before being immersed into a cosmic journey through the history of cinematic culture.

With total freedom to sit, walk, or stand anywhere in the room, the interaction with the rest of the audience’s facial expressions and turning heads merges with your experience. Together with a narrative conducted by alternating episodes of tension and release, it makes it all remarkably open-ended. As described by Hito Steyerl, it feels like ‘the viewer is no longer unified by a [linear] gaze, but is rather dissociated and overwhelmed’. Gone, Gone Beyond calls for ‘a multiple spectator’, who is created and recreated by ever-new articulations of the crowd1.

After Bennet’s five-year journey creating Gone Gone Beyond, she wants to continue working ‘beyond the frame’ and looking to innovate in audiovisual production in different spaces. For those who have missed it, Gone Gone Beyond continues its UK tour in 2022.

As a pioneer in audiovisual collage, how have you seen your making process evolve over the past 30 years? As more technologies were being developed parallel to your practice, how have they influenced your approach?

It’s changed gradually, and a lot, but the emphasis that may be worth noting is the shift between restriction to abundance and how to adjust one’s focus not to be overwhelmed. The main shift was at the turn of the century with the advent of (more) affordable high-speed computing and the Internet.

Gone, Gone Beyond is your first project housed in the CineChamber structure. How did you approach, both conceptually and technically, this screening design where the audience is at the centre of the experience?

Slowly! It took a long time to adjust to the idea of sculptural, physical media, something in an actual space. I would have the concept in my mind that since I already make collages, and that composition is collage (it’s a sum of the parts, more than the parts sometimes), I could perhaps pull it apart like a big deck of cards or an accordion. But then I’d actually try, and my mind would get in the way.

This went on for quite a while, and gradually I made some breakthroughs, which is in the way you think, almost going beyond thinking and analysis, and creating from a stillness within, just being still and seeing what is allowed to present itself. Something like that.

This was the point where I started dreaming scenes that I then wrote down, and we tried to recreate. The CineChamber concept is “VR mindset without the headset”, to quote Naut Humon, who conceptualised the CineChamber structure. It’s a shared space where the audience is actually a part of the piece because of the infectious interaction and pointing and turning; it’s a naturally social artform without the need for any social theme.

The opening of Gone, Gone Beyond – a surrounding landscape of dozens of candles in a darkened room – felt like entering into a meditative state before being immersed into a cosmic journey through the history of cinematic culture. Could you tell us more about the process for structuring and sequencing the piece?

Without wanting to give it away too much for those who haven’t seen it yet, it was designed to calm down the audience as they entered, moving them on from either chattering with each other or just within themselves. It’s trying to help people fine-tune their listening and seeing by starting with something lengthy and very quiet that doesn’t appear to change (although the candles really are burning and the sound continues to change). I think it sets people up well for whatever will follow in that hour-long experience.

Some of the source material in Gone, Gone Beyond were some of the best-known musical and cinematic works of the late 20th century. What attracts you to particular sources? How do you think it influences the audience, being familiar with the appearing films and audio?

I’ve always been a collage artist for over 30 years now. I use footage as my raw material and as my palette – but having said that, everything has a previous and later source; it’s all non-linear when out of the present. I’m more like a director and editor, but I call myself a redirector and decomposer because I cut and converse things into one another, exposing the skeleton beneath, taking things out of time by having them talk to each other in ways not possible in “real-time” life. Some of the footage is short or animated or photoshopped ourselves, and some are well-known preexisting footage.

I like to show how things are all connected and how things want to speak to each other and make that happen. Everything is connected, and time and collective experience are non-linear. Each person’s exposure is through their particular context, which means you might not find out about things in “official” chronological order; it’s just about what you have or hasn’t been exposed to before or after that point.

That said, children and even babies all respond well to this; they do not necessarily know or care about what I’m saying before. So this isn’t about “recontextualisation”, nor is it about nostalgia or other buzzwords. I am not trying to make things cute or cuddly; I like to make things psychedelic, to create and reflect magic and wonderment.

While experiencing Gone, Gone Beyond, my brain was constantly interconnecting thoughts, and several narratives were unfolding, creating a very individual journey for each viewer. How do these ‘unbounded’ narratives connect with the action of going beyond the frame in a 360º experience? What role do you think the audience plays in creating the meaning of the work?

That was my intention, so I am glad it worked for you. I suppose it’s the aim to go beyond or bypass the medium where possible since the word “medium” means a middle way or gateway between one thing and another… for cinema, it’s the screen or the projector; for sound, it’s the speakers. I think we are so used to speakers that we don’t really think about those, and sound permeates the air. But all the better when it’s around you. With moving images, it’s more unusual for an audience not to be on one side and the image facing them like a mirror or a frame on a wall.

The aim is to get beyond the novelty aspect; it is not enough to just present a showcase for surround A/V. I want people to forget the screens, and if they are interacting, it’s with each other and what’s beyond the screen. The audience is important because they help create the atmosphere, and we have the rare opportunity to face other people and watch their eyes and gestures, hands pointing, and heads turning. I think it works pretty well.

After this five-year journey creating Gone, Gone Beyond, what directions do you see taking your work into?

It’s a slow and long journey that I want to continue doing, working beyond the frame. But I am also about to make a 22-hour radio piece, have a solo exhibition in Walla Walla, USA, and make a video for The The. I would like to make some more radio shows on WFMU. Also would like to make some other immersive AV for different spaces, maybe using video mapping. I am looking for help, looking for support! Oh, and I want to make another album. So more of all of that. And have a rest too and go to the allotment and do meditation and the most important things to me.

What is your chief enemy of creativity?

Stress, fear and noise.

You couldn’t live without…

Quiet time.