Interview by Meritxell Rosell

Human beings have an extreme curiosity and capacity to understand and dissect what pushes our limits of perception, both on the micro and macro scale. But more importantly, to create something of taking beauty in the process.

In microsound electronic music, a form of extreme minimalism, the music is taken to molecular levels where sound particles are able to be manipulated to last less than one-tenth of a second. Recent technological advancements have allowed deepening in the exploration and manipulation of these particle sounds, but composers have used theories of microsound in computer music since the 1950s, including legendaries musicians Karlheinz Stockhausen and Iannis Xenakis.

Heir of these pioneers, American sound and installation artist Richard Chartier is one of the current biggest exponents of microsound. Even though he doesn’t consider himself a musician or a composer in the classical sense – he’s not musically trained and doesn’t take into play musical theories when creating sound pieces- his compositions are brutal minimalistic poetic musical statements. In our conversation, he shares his early love for machine sound, particularly that of a buzzing refrigerator in the house he grew up; one cannot escape the poetic minimalism of domestic concrete sounds.

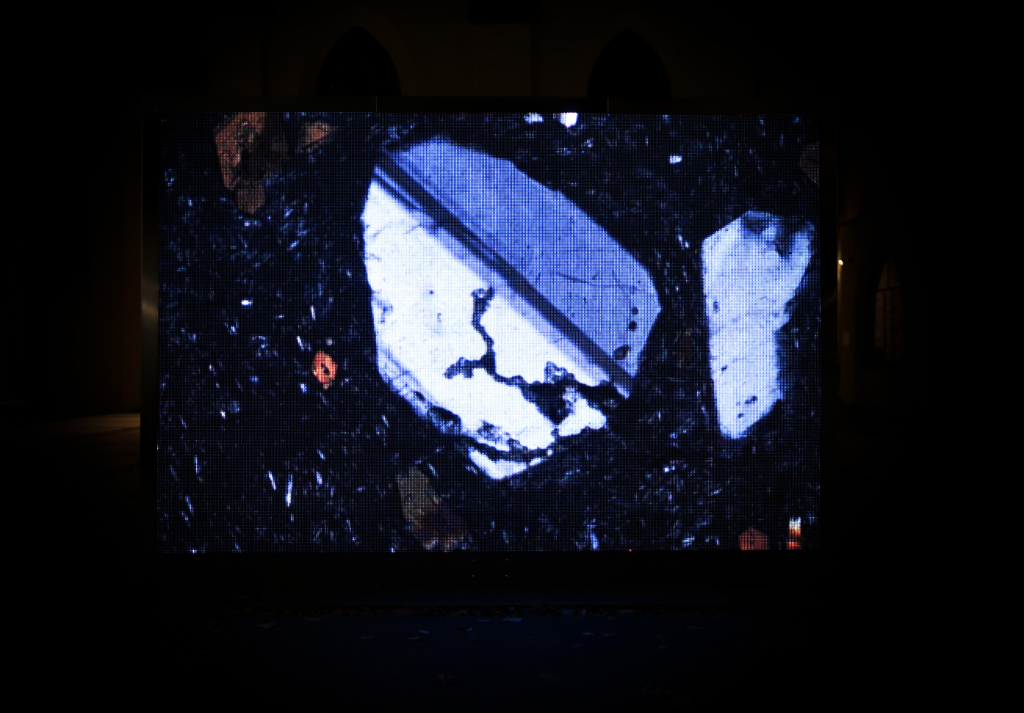

Chartier’s body of work is beyond prolific in all manner of configurations. Only to start with his solo work, which has seen him published in labels including Lawrence English’s Room40, Touch, Editions Mego, Raster-Noton and his own label LINE, to prolific collaborations with fellow musicians and artists such as Lawrence English, William Basinski, Yann Novak, Evelina Domnitch and France Jobin -among a myriad more- is with the latest with whom he’s released his most recent album, DUO (mAtter, 2018). A pulsating journey into deeply reflective mental and vibratory physical spaces. Jobin and Chartier will premiere an AV show of DUO, with visuals by Markus Heckman, at Mutek Montreal this August 2019.

In the last few years, Chartier has also been focusing more on another of his projects, Pinkcourtesyphone, which allows the artist to express a more emotional side of his work, often reflecting on queerness and gender. Chartier started Pinkcourtesyphone as a demo he planned on sending to Leyland Kirby (aka The Caretaker) for his VVM label in 1997, but the project has profoundly matured and evolved over the years. Pinkcourtesyphone takes inspiration from cinema, where the music, album, and track names are infused with cinematographic melancholia and quirkiness, partly influenced by Chartier’s move to LA.

We can’t help but wonder about the pink, which, besides the more obvious queer connotations, it also refers to pink noise, the artist confirms. Pink noise is the type of noise most common in biological systems (heartbeat rhythms, neural activity and even DNA sequences), a wink to this more emotional side of the project. Chartier is, these days, also a pivotal figure in the experimental art scene in LA, where he contributes with his compositions, installations and curational work to a thriving and extremely creative and honest community. Chartier will be releasing later in the year Variations in the idea of Completion on Ash International, the imprint of Touch’s Mike Harding.

You are an artist and composer considered one of the key figures in minimalist and reductionist sound art. How and when does the interest in sound come about for our audience not familiar with your work?

I have always been very interested in sound(s)… as a child, I was a very good mimic of sounds and noises around me. I really loved the sounds of machines. I have told this story before, but, in the house, I grew up in, the kitchen table was right next to the refrigerator, and I used to put my ear against it and listen. I loved the sounds it made, sometimes intense and vibrational, sometimes tiny and distant.

After a reviewer derided an early work of mine by writing, “my fridge could have made this album,” I actually took that as a compliment.

These types of sounds just set off something in my mind.

Artists like Zoviet France, Hafler Trio, and Pan Sonic were key in how I re-approached listening at different stages in my life.

I was listening to a piece by AGF yesterday incorporating radio waves, and I was instantly transported back to our basement growing up. We had a big 1930s radio from my grandparent’s home that I loved to play with. I really enjoyed the areas between these AM and short-wave stations. I think that says a lot.

Pinkcourtesyphone is one of your projects that -you share- has become a very important part of your work over the last few years. A space for your work’s more emotional and “musical” side. You started the project in 1997; how has Pinkcourtesyphone evolved throughout the years?

Pinkcourtesyphone started as a demo I planned on sending to Leyland Kirby for his VVM label in 1997. For some reason, I didn’t, and it just sat there until I dug it back out and started reworking it (+loops, sound files from that project) as the basis for the first album, ‘Foley Folly Folio’ in 2012.

Pinkcourtesyphone deals with many of my sonic and visual obsessions growing up, which may not relate to my work under my own name.

I expected to do the one album and almost release it without acknowledging I was the artist behind it. It got positive feedback and reviews, which overwhelmed me. I really enjoyed making the first album, and then I got asked for a second album by Lawrence English for his label Room40.

It’s a very different way for me to work; it’s much more intuitive and has a sense of freedom. I have enjoyed working with other live musicians and vocalists. They have brought a different sensibility to it.

Pinkcourtesyphone is a more open pathway for me; it can shift and be anything.

Your most recent release is DUO, an album in collaboration with France Jobin. Could you tell us what the intellectual and creative process behind the album was? Is it an experimental work, or did you compose the pieces?

The initial piece began as a composition I was unsure of; it felt like a dead end. I thought it might be a good starting point to work again with Eleh. He was rather busy then, and I reached out to my friend France. I have known her since the first Mutek in Montreal. She and I wanted to do something together, and I sent it to her, asking her sheepishly if she thought it was worth continuing. She said, “Mais oui!”

We started tearing it apart and rebuilding it from the ground up. I like working in this way. Something that began as its foundation, slowing dematerialisation over the course of the collaboration.

I am so happy that France and I got to create DUO together. The successful kind of collaboration, at least to me, is when you, as one of the artists, cannot tell who did what or how you arrived at that point. When everything meshes.

France and I are both hyper-detailed composers.

I have to say that the mastering that Stephan Mathieu did for DUO and its subsequent pressing on vinyl on mAtter, Japan, is just stunning. I was unsure how these pieces would come out on such an exceedingly temperamental medium, but WOW… it’s one of the nicest pressings.

I am so proud of the whole project. And it makes me happy that I could work with such a close friend on this. It was a long time coming.

Collaborations are at the core of your practice. How do you approach these? What challenges may you have encountered?

With collaborations, I like to know the person/artist. It’s not something that I would ever approach randomly. My process can be very slow and tedious.. but with collaborations, they can speed up and be a whirlwind (then you know the “magic” is happening).

Each collaboration is different, and I feel they only work when you approach the other half as equal. There can be no subversion or overpowering… how can these two halves become one?

The best collaborations, in my opinion, are when you (and the listener) can no longer make out who is doing or who decides what within a composition. I also find them successful if I go back and listen and cannot remember making it. The process fades away and becomes a mystery again.

You are also a graphic designer and visual artist. The Pinkcourtesyphone releases feel very cinematographic (very evocative of David Lynch, John Waters and the likes), and some of your albums with your Richard Chartier moniker are inspired by the work of visual artists and their imagery; in what way do visual art and images inform and impact your musical/sound practice?

I don’t think it has anything to do with John Waters (although I love his work)… it’s more linked to filmmakers like Rainer Werner Fassbinder and Douglas Sirk… and a lot of B movies.

I am not really a visual artist anymore. I was trained as a painter, but that process no longer makes much sense to me. It’s not a medium I can communicate through.

I am still inspired by colour, texture, and arrangement. I think very visually when composing.

Pinkcourtesyphone, in particular, is highly inspired by cinema (and dreams).

From a more technical aspect of your creative process, what is your relationship with technology nowadays?

Making something beautiful and evocative with the least means. I am not interested in the latest gear and plugins. I use only what I use because it makes sense and fits my approach.

It’s not the technology that makes an artist’s work substantive.

Your label LINE it’s dedicated to curating digital minimalism. How is the work of a curator in music selection, and how is your personal relationship with the “curator” word?

LINE has evolved over the past 18 years, and with 106 releases, I release works that I really enjoy. They can be outside of the traditional concept of what is minimal. It certainly doesn’t have to be digital.

The word curator is highly overused now. Everything is “curated”,… “a curated selection of artisanal raisins” etc. I am not sure how I feel about this term anymore. Words have meaning… but some words just become diluted and annoying in context.

And what direction do you want to keep for LINE in the future? Are there any territories you’d like to explore?

There is no specified path for LINE. There is, of course, a trajectory over time in a historical sense… but that does not mean it cannot change. It’s all about what I hear and what moves me.

Labels, in general, are facing an uphill battle.

With your work with LINE, you have frequently engaged with artists working in different disciplines, some of them using scientific concepts and methodology. Has having scientific input changed the way you approach your curational (or even sound) practice?

I don’t think it has changed my approach. I don’t think of LINE as purely academic or scientific.

Your chief enemy of creativity? (And what’s your secret to being so massively prolific?

Time, money and fear.

Creativity takes time. An artist should review, reflect, edit, and reassess.

I do not trust artists who think everything they do or have done is a masterpiece. A star mentality is not indicative of creativity or originality.

In regards to being prolific, some years are just busier than others. It all depends on where my mind is. I cannot force myself to create work. Forced creativity is a capitalist trap, and to be honest, capitalism (money) is the chief enemy of creativity. It’s now just exploitative.

The enemy of all creativity is competition. Creativity is not a war. Creativity is collaboration.

You could not live without…

music, beauty, love, and honesty.