Interview by Meritxell Rosell

Sound design is the [maybe not too so obvious but] intricate art to create soundtracks for a variety of disciplines, from filmmaking to television production, video game development, theatre, radio and musical instrument development.

Richard Devine, a prominent figure in electronic music production, has longly been doing sound design for various industries. He’s worked with Apple, Nike and Google, and more recently with Jaguar, designing their new electric cars sounds (electric cars’ motors can barely be heard, which is a challenge for safety reasons). But apart from that, Richard Devine is also a musician, a producer and a pioneer in the development of analogue and digital synthesis technologies.

Starting his producer career in the mid-90s with releases in Warp and Schematic, the work of Richard Devine has had a profound influence in the most recent history of electronic music despite being a less media-perceivable figure than other electronic music artists such as Aphex Twin, Squarepusher or Autechre. Devine is also well known and respected for his work as a modules and synths tester, and he was the first artist to release on Tony Rolando’s Make Noise Records for the Shared System Series, a series of productions that compiles the separate recordings of different artists utilizing the Shared System, one of the popular modular systems from Make Noise.

From a more conceptual perspective, Devine’s work is strongly influenced by the research on modular synthesis, randomness and the more abstract aspects of music composition. Devine has been trying to understand the mathematics of music or sound through synthesis randomness and challenging what lies beneath, that randomness is never random. There are some intrinsic mathematic patterns which, inasmuch randomness you try to input in your system, always ends up following a pattern and sounding in a sort of coherent way. With his compositions, Richard Devine has been pushing randomness to escape from mathematical patterns to serious limits.

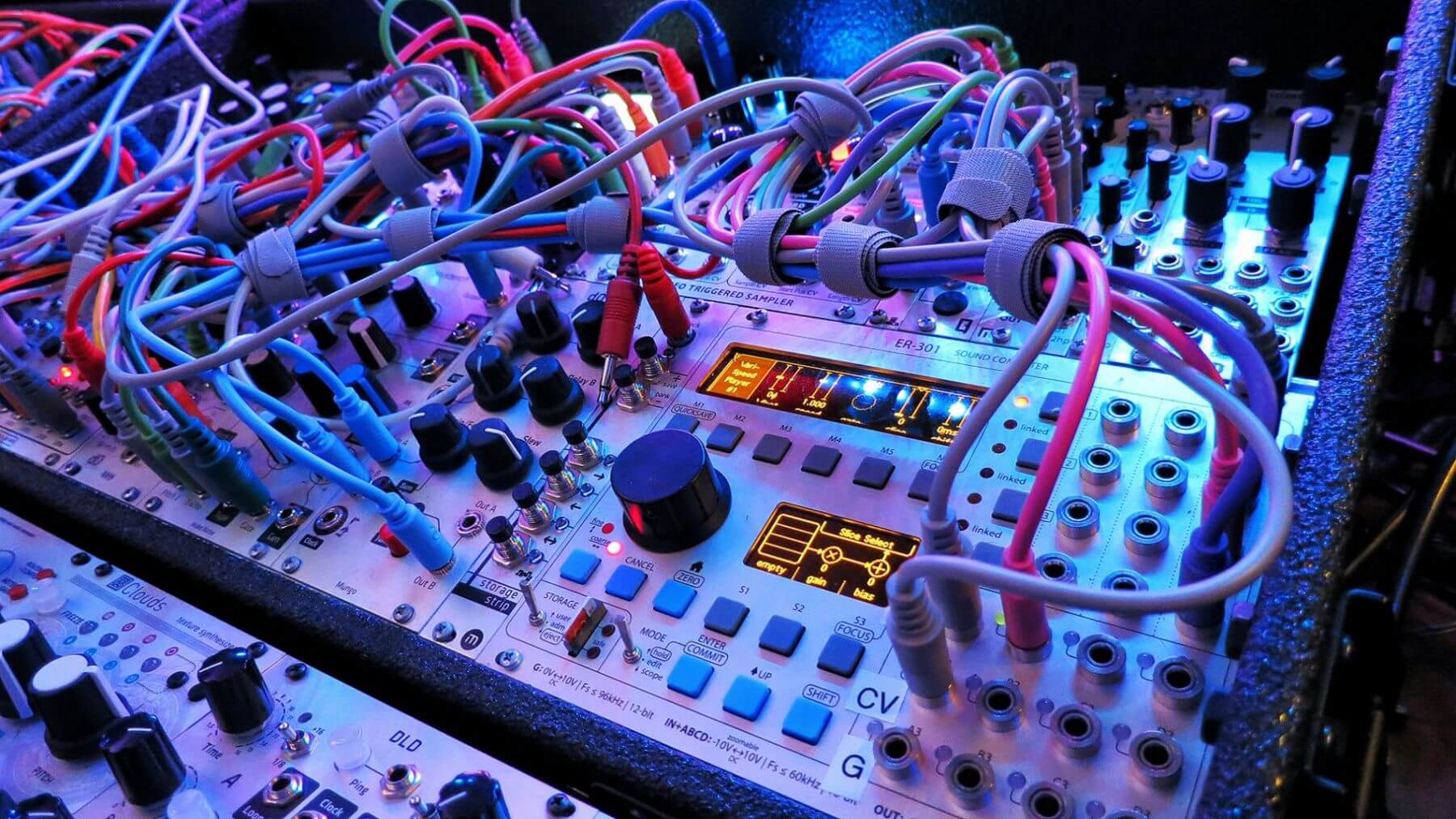

Last October, after a break of 6 years, he was back with a new album Sort\Lave published on Venetian Snares‘ Timesig imprint. For the last 5 years, Devine embarked on a long modular synthesis journey and spent about 5 years building up the Eurorack systems that he used on this album. Devine recalls using modular synthesis since an early age: I’ve been using modular synthesizers since I was 17, but have never written complete tracks using these newer systems. For Sort\Lave, he wanted to sound very different to his previous works which had been more cold, digital, clinical even and had all been made using computers.

The tracks are a raw and visceral mix of intricate abstract electronica, from abrasive percussion to a more metaphysical ambient. It feels like the artist is picking up where he had left off after all these years and developing further his creative language. With the new system and the record in mind, that became a new way of creating music, with a set up closer to a live setting: the tracks are more like captured snapshot performances where I could experiment and play around with the idea of probability-based sequencing for every patch, string multiple sequencers together that would feed other sequencers to come up with interesting rhythms and melodies.

The artist also keeps an eye on new technologies like Google Magenta. He thinks that the idea of exploring the role of machine learning in the application of creating art and music is fascinating and that he is curious to try and abuse this technology in a different way: like confusing the algorithms to come up with completely new results. A relentless researcher, we’ll hope to keep seeing Richard Devine pushing the limits of the audible to places he still may be only starting to imagine.

You are a programmer, sound designer, and composer. For those who are not that familiar with your work, how and when do the interest in music composition and sound come about?

I began writing my own music back in high school. I think it was around age 17, after DJing music for almost two years. I decided to take the leap and try creating music of my own. The reasons at the time were purely because the music I was into at the time was fairly new, and there weren’t many artists creating this type of music. For me, it was the music of Richard D. James and his Rephlex Records that influenced me early on. I only had enough records to play for about 20 minutes.

My goal at the time was to be able to play at least an hour + of music that was in a similar vein. So I decided to create my own tracks that could mix with these other records. It was from this point I became obsessed with building up my own studio and creating my own sound. Before this, my mother had gotten my brother and I into taking piano and guitar lessons. So I had around 8 years of classical piano training under my belt before jumping into composing seat.

In your new record Sort\Lave, which comes after a 6-year hiatus, you use a custom-built Eurorack modular system and two Nord G2 Modular units. What makes their sound unique?

I think it was a combination of different things. I have actually been using modular music systems since the beginning. My first analog synth was the Arp-2600 and one that I still use here at my studio today. I purchased it from a pawn shop here in Atlanta, I believe, around 1991. It was my introduction to the world of analogue synthesis. I learned a lot from that system in that it taught me all the basic fundamentals of sound shaping, VCOs, VCF, VCRs, AM, FM, Ring modulation, sequencing, and noise generators.

From here, I discovered other modular synthesizers by buying the EML-101 and EMS synthi AKS. I discovered many things about these instruments during that time period. These systems had an open architecture where you could explore different patching options every time. The result would almost never be the same. The temperature of the room could cause the circuits to shift or detune.

The interaction between different systems would also change the behaviour of how each system would sound. I would often patch all these systems into each other to see what would happen. It was like this alien language or conversations happening between these different instruments. To me, it was fascinating hearing and exploring all of the different patching configurations.

The most interesting aspect was the sounds I was getting, which sounded to me like it was electricity coming to life. The usage of control voltages created this web of constantly organic moving textures. Everything wasn’t exact or perfect, like producing within a digital computer environment. It was the exact opposite. Things where broken, spontaneously exploding, modulating, and happy accidents would create entirely new ideas on the fly.

You spend 5 years building up the system; what were the biggest challenges you faced in its development?

It took many years to test out different modules. I tried lots of different configurations. My goal was to design a system in which I could write music very quickly on. I also wanted to design a system that would allow me to test out different ideas and also generate rhythmic/melodic sequences on the fly. I have two cases in which I do all the testing, in “floating cases”. In these two cases, I have nothing screwed in.

The modules are just plugged into the power buss. I can just change out different modules and try new things at any point. I would spend many months trying out different combinations to see how it would improve my workflow. I eventually got to a point where I had 5 to 6 cases that would be set up to work together to record each song.

One case would be the master clock, and then everything else would slave to that case. I came up with a system to divide the composition into separate parts/movements that would only play at certain points within the piece. So, for example, the first case would only play the first two minutes of the piece, the next case would play the next 2 minutes etc.

I would have transition points when moving into different parts of the arrangement. It was designed so that I could do everything live and be controlled by hand. I wanted to be able to be able to change the direction of everything at the turn of one knob.

In a conversation with Tony Rolando, he described how using a modular synthesiser is a collaboration of human and machine and that the device is highly capable of being guided but must even be allowed some freedom. What’s your relationship with these modular systems?

I completely agree with Tony’s statement about it being a collaboration between you and the machine. It’s more like you’re having a conversation with the machine and expressing that idea to an audience. What makes these modular systems so fun to work with is that you start out with a blank canvas at first. You have to define all of the parameters and where the system will go.

You build up a little floating electrical network that is suspended in between all the wire connections. It’s a careful balance of push and pull and making something musical happen within that. It’s fascinating in that it’s like this electrical entity that is only there for one moment in time that you have to capture and record before it disappears.

I don’t know any other instrument that allows you to interact in such a way. For me, it’s inspiring, and the spontaneity of happy accidents that can occur sometimes steers you to a completely different place.

With your work as a sound designer, working for companies such as Google, what do you think of inventions like the ones produced by Magenta and new developments in AI-assisted music composition and music produced entirely by machines?

I love this idea, and I know Doug Eck, who is the main research scientist working on Magenta. I had a few meetings at Google with Doug and his team. The idea of exploring the role of machine learning in the application of creating art and music is fascinating to me. I am curious to try and abuse this technology in a different way, like confusing the algorithms to come up with completely new results.

What if you fed the algorithm strings of musical information that was mixtures of different time signatures and chaotic sequences? Or feeding edited musical compositions where you’re mixing 4 to 5 different styles of music. It would be interesting to explore the different outcomes and then apply this to different timbres and textures. I am always interested in seeing how something like this could be used in the wrong way.

What’s your chief enemy of creativity?

For me, it’s just not having enough time to create. I have so many ideas that I want to try, just not enough time to get to them all.

You couldn’t live without…

I would say, my family and my two crazy kids. They are a constant source of happiness and entertainment in my life. Having kids has let me be a kid all over again, loving every minute of it. Haha.