Text by Miguel Isaza

The avant-garde, by nature, implies more than following patterns. It is a sense of transgressing the tendencies as such, questioning them and even more: proposing new ones, sowing other questions, avoiding isms and generating an always fresh flow of intersections, mutations and novelties. It’s not just about merely staying on top of the trends, but above all, to keep generating new routes, staying away from the comfort of it and being able to invent constantly.

This is something German label raster has been doing for years, something which has led it to position itself as an unavoidable space for anyone who wants to listen to the most advanced musical avant-garde and futurist thinking of recent years. More than a label, a house of thought and a creative family, raster has made its place in the history of music due to its sonic finesse, the depth of its manifestations and careful graphic design, along with their conceptual and procedural style.

Since its inception, the label has been a perfect example of what it is to be at the forefront, not only for the innovative fact per se but also because of how diverse perspectives are integrated and continuously updated through the years in a movement that always seems to be a portal of tomorrow, a crack in space that manages to be permanently current in times to come.

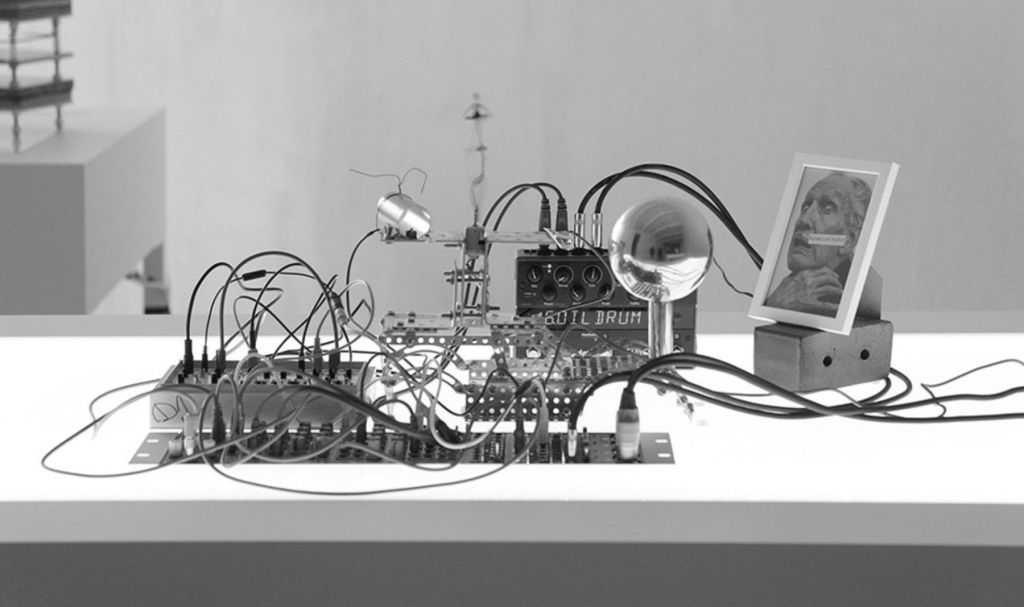

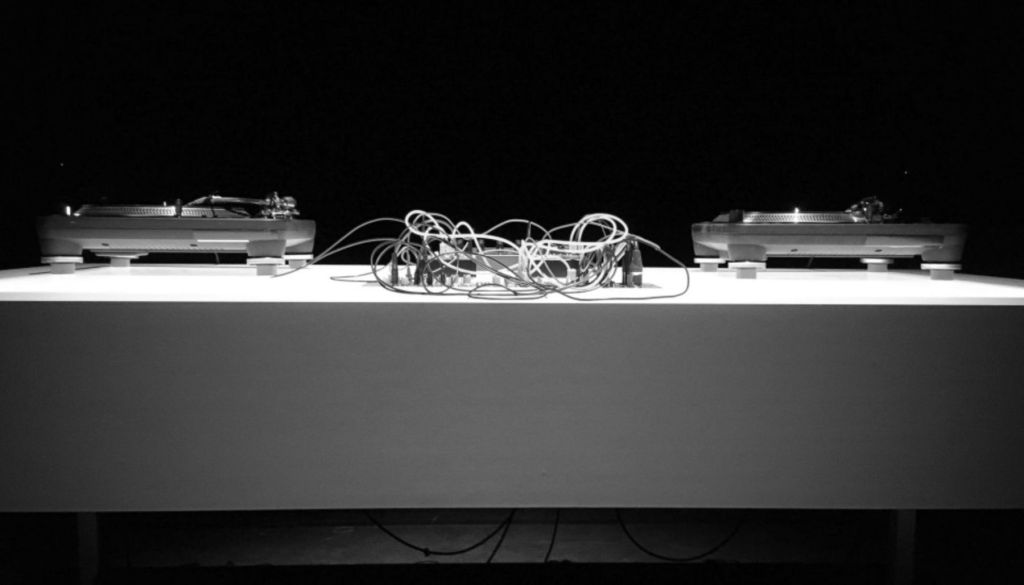

This is also materialised through the use of cutting-edge technologies by its artists or for being pioneers in post-digital sonic reflections, thus exposing an artistic diversity that usually deepens conceptually and visually parallel to the sonic element. Perhaps this is one of the most outstanding characteristics: a kind of data synesthesia in which ideas, sounds and graphics are permanently intertwined to condense a series of works. It could well be considered a universe of experimental surprise, in this case, full of silences, glitches, pulses, machines, algorithms, cuts, lines, dots, lights or letters.

It is precisely this worldview that makes raster an essential space and which allows the label to always remain in its own and ever-expanding niche, forged both by new artists who keep the house’s perspective fresh, such as Novi Sad and Island People, as well as veteran agents in the family. From the eclectic views of people such as Ryoji Ikeda, Kyoka, Dasha Rush, Richard Chartier, Mark Fell and Mika Vainio to the electronic and dance-oriented processes of other masterminds such as Aoki Takamasa, Kangding Ray, Grischa Lichtenberger and Byetone, the latter head of raster since its inception.

Byetone has also been an active artist of the label who continues to develop his immersive performances to this day, similarly to the prolific and proactive Atom TM, a philosophical and aesthetic algorithm that has launched a ton of pieces with the label from its early days to the present, including his most recent album ‘neuer mensch’. We talk with Olaf Bender, raster’s own Byetone, to discuss their career, vision and future prospects for the label.

How do you conceive the future in terms of music and media, and how has your conception changed over the years?

In times when music is omnipresent, and nobody is able to keep track anymore, we define ourselves more as a filter for artists and their products. This is especially particular in electronic music and its intermediate zones, i.e. beyond style and trends. It is just as important to us today as it was 20 years ago to present new music and express our trust in artists who are not yet well-known.

What is your current process of selection/curation of artists? How open are you to new artists compared to those already part of your roster? Are there any particular guidelines or strategies you follow in terms of curating?

Of course, we are a label that deals with electronic music in the broadest sense. So, when we hear material that is produced in this way, I am initially only interested in whether there is an independent artistic expression. Something that fits the person in exactly this way and can only come from them. The next step is to get in touch and see if there is a connection on a human level. We don’t see ourselves as a service provider but as an artistic platform, so we always have an interest in the respective artist fitting into the entire »artist family«. Modernity is also important to me, but it’s not primarily about technology.

In recent years, your yearly releases have decreased compared to previous years. Is there a particular reason for that? What’s your position on the current way of releasing music? Also, what are the main challenges releasing music you face nowadays, especially regarding digital format and the way music is currently promoted and published…

The problem is that with the digital possibilities today, everyone is constantly shooting and, so to speak, wants to keep themselves or their products in the conversation at any time. Personally, that annoys me, so in the past few years, we have actually been trying to work towards a good balance between making ourselves rare and, at the same time, giving weight to our statements without imposing ourselves. That sounds a bit helpless, but to me, it seems to be the only way to remain credible in the long run.

What was the impact of the pandemic on your work as a label and the events/projects you developed

We were actually quite happy with the development at first and noticed a significantly increased interest in music for listening, probably due to the cancellation of festivals and live events. It also gave us an opportunity to rethink strategies and activities together. However, I am rather sceptical about the long-term consequences of the pandemic; our current reality (high inflation, lower income, uncertain planning, etc.) is having a rather negative effect. There is also a strong tendency to control artistic content through government funding. I’m rather sceptical about that, too.

What’s your take on the current state of the German scene? How do you see yourselves in there?

That is a difficult question. I never really saw myself as part of the German scene or any scene at all. For a few years now, especially in Berlin, there has been a tendency for interesting things to happen in smaller formats rather than at large festivals or in established clubs. But the scene itself is more diverse than ever. Another novelty may be an improvisational attitude or an emerging improv scene.

You give huge importance to the conceptual process developed in your releases and projects. How is it approached? How do you collaborate with artists for that? Is it a back-and-forth process? Is it more something you want to trigger or suggest in the artists’ vision, an opening to their ideas or both? How do you collaborate?

The collaboration between the artist and label is, of course, two-way. As a label, we actually try to place the material in an overall context. It can be a series, but it can also be a specific format for a specific release. Otherwise, I recommend that the artists not always pack all their ideas into each track but maybe stick to one topic separately for certain releases.

What is the evolution of your idea of experimental? Has it remained the same, or have you seen a change in your approach towards what “experimental” means for you? Related to that, I wonder about the other two concepts in your definition of Raster: how would you define “groundbreaking” and “non-commercial” in terms of music? What’s the aesthetic pursuit behind those?

In its original sense, an experiment is something with an open outcome. In this respect, experimental music should somehow surprise us. But then, there have been so many experiments in recent years that the experiment in particular no longer surprises us. This is decided on a case-by-case basis and certainly also an individual impression.

I also don’t think it’s possible today, like maybe 15 years ago, to create something that’s never been heard from scratch. And yet, with a little distance, you can hear projects that sound very similar on the surface but still have big differences in the details; above all, in their own claim, which the musician defines for themselves. Some want to please, experimental or not. Others are really trying to work on structural issues.

You have a very special conception of sound and sonic matter, often related to microsound, glitch, digital and post-digital ideas and processes, etc. Would you accept the idea of sound as a kind of matter? Or what would be your idea of sound, and what interests you, particularly of it?

I really like listening to the machine the artist works with. I have always preferred the rather raw sound of these tools, whether analogue or digital, to an elaborate sound design. But I understand it when an artist declares a certain sound design as a concept. Like the current AtomTM records, for example.

From the beginning, you have been developing a strong visual aspect for the raster project, as shown in events, audiovisual performances, and the artworks of your releases. Could you tell us more about your vision regarding the visual aspect of your label and the routes it has taken since your first releases to the current days?

Instead of design catalogues and architecture books, I’ve always been inspired by not-over-designed everyday things like printed packing slips or textbooks. I’ve always tried to transfer these aesthetics to our musical products because music in itself is a highly emotional good. If you have a ballad, I don’t need the sunset to go with it. To me, things are more exciting when they’re in conflict at first sight, or the connection isn’t that obvious. At the same time, I don’t want to establish any new isms, and sometimes it’s also necessary to follow the artist’s concept and put our label claims in the background. All in all, the best design for me is a non-design or a purely functional one.

Among all the artists in your family, Atom™ has been particularly proactive in the last few years. What do you think about his process as an artist? And particularly in terms of Neuer Mensch, it seems to consolidate his reflection around artificiality and algorithmic reality, defining himself as code and developing music that is so machinic yet very unpredictable and asynchronous at times. How did you approach this particular release? And how is the process of collaboration with him, who has been on the label for so long?

I think Uwe’s concept has been consistent over the years. He always creates themes for himself, which he then works through with precision. At the moment, it’s probably a dystopian vision of the future, but I see him more as a philosopher in the guise of a pop artist.

Working with him is fantastic. Without wanting to criticize the other artists, Uwe is the only one who tells us in February that his material will be ready on date X and then will also be delivered on that day.

What’s coming for you in terms of releases and projects? Also, is Electric Campfire returning at some point?

Unfortunately, we had to postpone the Electric Campfire once during the pandemic, but we were finally able to catch up on it in spring. That’s why there will even be a 2nd Electric Campfire this year! This year’s regular edition will take place on August 20th in Fano/Italy.

As regards new releases, there will be several artists with their debut albums appearing this year, plus a long-term collaboration with the Max Planck Institute for Empirical Aesthetics that will take up the archive idea of the label again.