Text by Katherine Jemima Hamilton

While Kwon’s undertaking is grandiose, it is not naive that she would believe in the power of technology to usher in a feminist utopia—time and time again, feminists have appropriated technological advancement and its discourses. In 1985, Donna Haraway wrote “A Cyborg Manifesto,” where she argued that feminism’s path to the future required the destruction of rigid boundaries and hierarchies between humans, animals, and machines.

Like Kwon, Haraway understood the blending of technology and humans as potentially liberatory for women (who, according to Haraway, are not essentially bound to each other), as there would no longer be a category of “woman,” “man,” or even “machine.” Like Kwon or Leymusoom, the cyborg is omnipotent, using the knowledge of every brain they are made of; and every experience of their predecessors. Thinking of Leymusoom as an inherently rhizomatic project, one that is made of webs of lineages over structured, hierarchical family trees, Kwon aligns herself with the internet’s purported queerness, creating kinship through and beyond binaries [1].

Digital technology is an expansive category for Kwon. Photography and its presentation have been vessels to develop her hybrid utopia and the beings who reside there. Her lenticular lightbox prints show a series of images where Leymusoom, the serpent spirit, guides Kwon and her ancestors in one panel, vanishing in the next. Underscoring Leymusoom’s immaterial presence on Earth, she flits in and out of the images Kwon materialized of her ancestors, slipping out of sight between photons and atoms.

In Premolt 8, Grandma Kim stands at the stove in a 1990s kitchen with a beige tiled backsplash, one hand holding a white decorated plate and the other placing a lid on a pot. One of many manifestations, Leymusoom places her hand on her grandmother’s shoulder, gazing at the viewer more confidently than the woman she watches over.

Leymusoom’s presence wavers step by step, disappearing and reappearing depending on where the viewer orients themselves in front of the image; perhaps an on-the-nose metaphor for accessing a different world depending on how we orient ourselves to our beliefs. Leaning into the ephemerality of the goddess’s presence further emphasizes her cyborgian nature: appearing only through small, fleeting moments, Leymusoom and her world must be searched for and located, as she is made of many realms and belongs to none.

Bending light to interlace worlds embodied and imagined, Kwon demonstrates how Leymusoom, as a practice, transcends time or physical space, as it can be ascribed to a person, place, or time after they have passed. Leymusoom can rewrite history to remould the present and radically shape the future.

As I relay Kwon’s story, I wonder: why must women hide between realms or in bent light to experience utopia? Why must we act in shadows, surf invisible web waves, or slip between the imagined and the experienced to glimpse at the lives patriarchy refuses us?

I may be asking the question the wrong way. Is it not hiding or slipping by night to avoid the eye of an oppressor, hopeful they might gain access to these utopias, but more about the expansion of our world into realms unexplored or not yet territorialized by patriarchy?

Do we admit that we will never see these utopias in our reality, so we must imagine them (locate them) elsewhere? As I ask these questions, I think of other times, historically and more recently, when women responded to their real-world oppression by summoning other women from history and myth into an incorporeal space. The Book of the City of Ladies was written by Christine de Pizan in 1405.

Christine was born in Italy and then moved to France, where she was the first professional female letter writer in Europe—or so she says. The Book of the City of Ladies was a response to the wildly popular and profoundly misogynistic texts published at the time, which disparaged women and claimed they were inferior to men.

Pizan sought to demonstrate women’s equivalence to men by citing examples of famous women who were strong, courageous, loyal, or embodied other qualities valued by medieval society. Each woman Christine cites builds the city of ladies, as the city is, in fact, a metaphor for the structure of the book where they reside together. Leymusoom’s digital world reflects this idea of women inherent to a utopian society’s infrastructure, as Kwon chooses and 3D models sites from the physical world—often built by her ancestors—for Leymusooms to inhabit. Each ancestor is the building block; each familial tie is a drop of the ocean.

Like Kwon, Christine conjured an expanded set of ancestors into a single space, hiding the women between the pages, solidifying them as the bricks of a city held entirely within the letters of her anecdotes. In a way, it is safer to relegate utopia to a world beyond the physical realm: if it is destroyed or corrupted, we could say, “It’s not so bad; it was an imagined world, anyways.” The risk of being foiled is greater, but so is the reward.

Kwon’s latest unfinished venture merges “real” and “imagined” sites even more closely, collapsing space and time to create ghosts of the future rooted in ancestors of the past through technical manipulation of analogue family photos. Leymusoom Firefly is a series of photos Kwon runs through an artificial intelligence filter to expand the images’ settings. Though the technology typically extends the room where the photo was taken, it sometimes mistakes (or transforms) a light leak or dust spec for people who never existed.

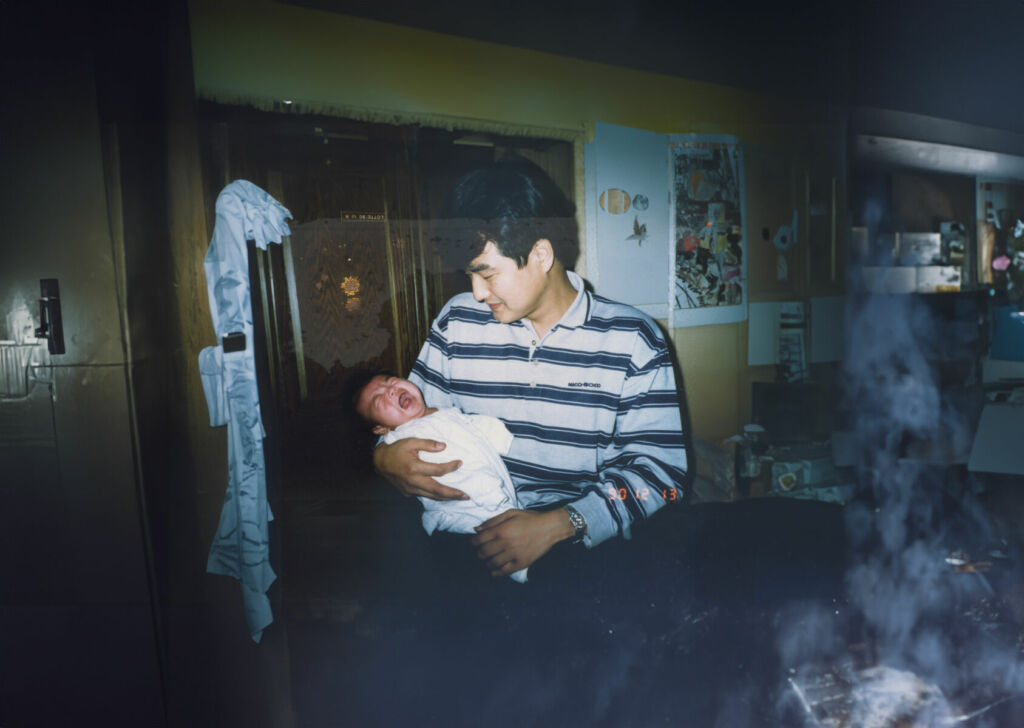

These figures are not only cyborgs of physicality but of time, existing in eras their cells could never know. In an image of Heesoo as a baby wailing in her father’s arms, a ghostly smoke rises from the bottom right of the AI-invented scenery. Kwon’s father beholds his crying newborn daughter with a hint of annoyance but general amusement for this tiny being’s reactions to its new world. No attention is paid to the heavy blue-grey smoke that rises from an unknown source into the room. Of course, to read the subjects as aware of the ghostly AI-generated presences would be anachronistic, but we can only read images as they are presented to us.

In another photo of the infant artist with her father, a spotlight opens on a family of three: Kwon, her Father, and a woman made of pink light, originally a light leak in the photo’s corner. Who is she? Where did she come from? And has she always been there? Like the spectral Leymusoom portraits, the subjects of these photos are at ease with the technological ghosts, the ancestors invented by a computer program. In the way a spirit could be stuck in purgatory on the physical plain, awaiting justice before they go on to the final afterlife, perhaps some are stuck in the machine, awaiting liberation to move on—where to, neither Kwon nor I are sure.

Of course, the use of AI brings its own set of ethical conundrums, but when we consider it as another tool for ritual—a tool to expand images or memories beyond the physical plane and into the spiritual-digital—we can more clearly see how past and present are merged as one.

This type of imagination, this location of another world through the digital, is vital to our lives as present-day women. Free of physical and poli-social constraints, we can impose our own rules on the worlds we make and can imagine the cycle of patriarchy broken; we no longer write treatises or essays asking for humanity from a group that benefits from our oppression. Kwon recounted to me that “Digital space overcomes the gaps.”

The gaps between time, between stories and experiences. I think this way too about writing, literature, and books as an early type of “technology,” in the way that Ursula K. Leguin argues the basket was the first piece of technology, not the spear [2]. In Kwon’s expanded understanding of “ancestor” as encompassing land, story, myth, and mechanics, her ancestry might extend to all women building utopian worlds “elsewhere.”

Haraway closed her discussion of cyborg theory by looking to the future with two possibilities for feminism: on the one hand, a future where the boundaries between organic and technological bodies were completely broken down, thus liberating oppressed bodies, and on the other hand, creating kinship between boundaries and accepting fluid, malleable, contradictory identities. When Haraway finished her essay with “I would rather be a cyborg than a goddess,” she favoured as Jasbir K.

Puar summarised the postmodern technologized figure of techno-human over the reclamation of a racialized, matriarchal past, thus implicitly invoking this binary between intersectionality and assemblage [3]. What binaries Haraway favoured or created is not a matter of my mind. Practices like Kwon’s don’t seem to mind these binaries or categories of bodies in the first place. Kwon’s cyborgian shamanism is contradictory; it is impossible. And yet, it is her reality. She is made of every perspective held in her lineage, even if the ancestors we witness were modelled by her own mind.

Following the night in the basement, the night I converted to Leymusoom, I fused my ancestry to Kwon’s and every other person devoted to Leymusoom’s teachings. Leymusoom is a chimeric, monstrous fusion not only of Kwon’s matriline but of anyone with ancestors who wants to believe in better lives happening everywhere all the time. She is formed of all parts, never whole or final because she is a practice, a devotion. In Leymusoom, there is no need to choose whether to be a cyborg or a goddess—the goddess is a cyborg.