Words by Lula Criado & Meritxell Rosell

In his seminal 1964 work Understanding Media, philosopher and media theorist Marshall McLuhan claimed that the medium through which a message was transmitted was so meaningful that it represented the message itself. Some years later in Simulacrum and Simulation (1981), Jean Baudrillard, a pioneer theorist in electronic and digital arts, imagined that the hyper-real digital context was “a gigantic simulacrum – not unreal, but a simulacrum.” For Baudrillard, the fact that simulacra had replaced representation in contemporary society was a presage at the time.

Fast forward five decades, and even though our media forms have profoundly changed, the symbiotic relationship between the content (message) and the channel of communication (medium) still stands stronger than ever before. Furthermore, in our so-called Post-Internet and Post-Digital era, the “digital” (or the simulacra in Baudrillard’s words) is ubiquitous; it has permeated our everyday existence to become one with human life in a way that this statement seems understated; The simulacra have been more than a presage, it has turned into reality. The digital has become an intrinsic part of us.

During the 90s, the English computer scientist Tim Berners-Lee invented the World Wide Web, and Nicholas Negroponte (founder of the MIT media lab) predicted the massive impact of digital technologies: ‘Being digital is a way of living and is going to impact absolutely everything [1].

Now, this prediction seems to be coming to fruition as digital art is enjoying a momentum of mainstream acceptance like never before at major institutions across the globe like the exhibitions Electronic Superhighway (2016) at Whitechapel Gallery in London, Open Codes. Living in Digital Worlds (2017) at ZKM in Karlsruhe, Artistes et Robots (2018) at Grand Palais in Paris, Programmed: Rules, Codes, and Choreographies in Art, 1965–2018 (2018) at Whitney Museum in New York, Regionale 20 – Avatars, Doppelgangers and Allegorical Landscapes (2019) at HeK in Basel.

However, computers (and the internet posteriorly) have influenced artists since the mid-1960s. This became even more obvious after the 1990s when artists began to explore the creative potential of digital technologies and the Internet, demonstrated by the rise in cybernetics -defined by the MIT mathematician Norbert Wiener in 1948 as the scientific study of control and communication in the animal and the machine.

Take, for example, pioneer video artist Nam June Paik, who is considered to be the founder of video art (credited for coining the term “electronic superhighway” in 1974, foreseeing the potential of global connections through technology) and many of his Fluxus pioneering artist colleagues and collaborators; these artists took the visionary work of Wiener and the electric prophecies of McLuhan and created art that posited potent possibilities for cybernetic consciousness and ecological human-machine systems. In short, these artists explored and prompted the prospect of an egalitarian, democratic society through electronic media.

In the last few years, the impact of these digital technologies on society and the aggressive increase of everything post-digital and post-capitalist has given artists a reason to examine further the role of technology (with its pros and cons) on our [media] environment. Thinker, writer, and philosopher Paul B. Preciado in his book Testo Junkie (2008), portrays a brutal techno-capitalism as a dominating force that controls our sexuality, reproduction, gender, and identity through lab-engineered synthetically produced hormones and the wide digital spread of pornography.

In Technocapitalism: A Critical Perspective on Technological Innovation and Corporatism and Globalization (2012), Prof. Luis Suarez-Villa explores the emergence of a new version of capitalism grounded in technology and science and the political economy of corporate power and its influence. Prof.Luis Suarez-Villa’s work involves the concept of techno-capitalism, a new version of capitalism with major potential systemic implications for human existence, life, and nature, as well as the economy and society, painting this techno-capitalism as a pathological entity.

Another theory examining capitalist behaviour is contemporary accelerationism [3], which advocates the acceleration of capitalism to free ourselves from it. Accelerationism is defined as a radical socio-political theory that states that the idea that capitalism -or particular processes that have historically characterised capitalism-should be expedited rather than overcome to generate radical social change. Modern accelerationism saw the light in Nick Land and The Cybernetic Culture Research Unit (CCRU), an unofficial research unit at the University of Warwick that was most active from 1995 to 2003, with social theorists Sadie Plant and the late Mark Fisher also contributing as key progenitors.

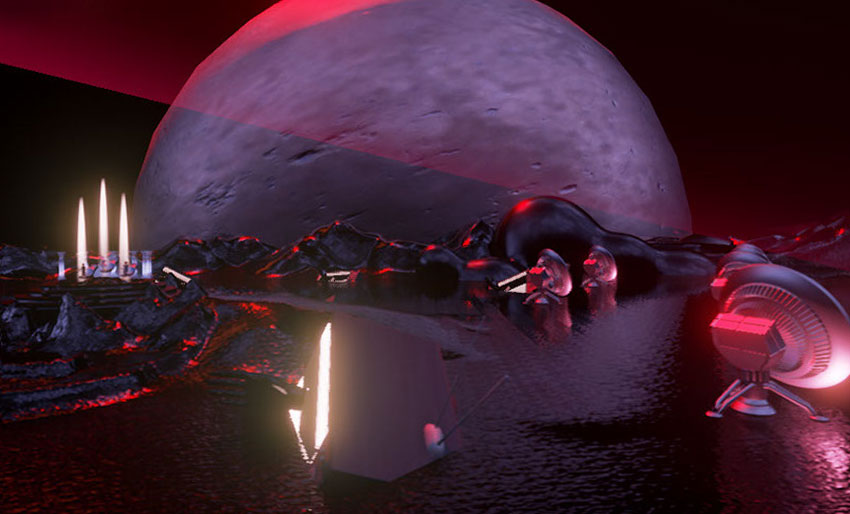

Artist and musician Kode9 was also part of CCRU. One of his recent works, The Notel, is an audiovisual collaboration between him and new media artist Lawrence Lek which imagines a futuristic techno reality filled with emptiness and void. One of Lawrence Lek’s latest solo projects, AIDOL (2019), lies at the heart of these techno “irrealities.”

AIDOL is an alternative digital reality, a computer-generated fantasy that revolves around the long and complex struggle between humanity and Artificial Intelligence. It defines the concept of genre, engendering a fictional space as in previous works. Lek’s imaginary world is inspired by techno-orientalism. It operates within the dichotomy of the real world versus the simulated, the shimmering utopia versus the automated dystopia, and the ‘human’ versus the artificial intelligence.

In 2019, it certainly felt as though we were immersed in accelerating economies and societies. But does this acceleration mean we are any closer to destroying capitalism? And at what cost is this happening? Every day new research indicates that we are on the verge of destroying most of the living species on Earth. Some artists, such as Jakob Kudsk Steensen reimagine new ecological realities as a symptom of the exhaustion of our current ones.

In Re-animated (2018), the artist re-animates an extinct bird from the island of Kauai. Performing the role of a digital gardener, Kudsk Steensen digitally reconstructs the landscape of the Hawaiian island of Kaua’i. The piece is a product of extensive fieldwork conducted to collect and 3D-scan flora and fauna, as well as collaborations with museums, interviews with ornithologists, and inspiration was taken from paintings of the now-extinct bird. Some of Jakob’s landscapes may appear dystopian, but the notion of re-animating life is inherently optimistic. By means of digital recreation, we can imagine new ecological futures.

And what is happening at a more personal human level, with the ever-increasing number of social media platforms, newly created identities, personalities and digital avatars? Rapid progress in Artificial Intelligence, Machine Learning and the advancement of digital tools have changed how human beings relate to their environment and have raised concerns about these technologies’ societal impact and potential risks. We live in a world where the digital is suffusing all material existence, with AI and artificially engineered realities at the epicentre; deep fakes, social network opinion manipulation, mass surveillance…

There has been a lot of criticism against popular social media platforms like Twitter, Facebook, and Google related to issues of surveillance and privacy, harassment and abuse, mental health, fake news, and racist and sexist algorithms. Artist Benjamin Grosser, for example, in his Twitter/Facebook Demetricator (2012-2014), creates an alternative digital reality in which he removes all metrics from Twitter and Facebook. What happens when we lose all these markings? Immediately, feelings of competition are lost.

In conversations with Grosser about his experience with these experiments, he shares that when we see how many “likes” our last post received, we can’t help but consider that when we write our next post. In other words, the metrics are guiding and changing what we say, how we say it, and who we say it to. By removing metrics entirely, Grosser’s extension allows us to focus on the content—to be free to write and post without worrying about what will get likes and to decide for ourselves if someone is worth listening to. Additionally, it allows us to push back against an unhealthy system designed to prioritise user engagement to sell ads.

Another contemporary topic involves the recent feminist and gender movements, which have prompted us to rethink one of our biggest societal struggles with technology. Something that started almost 50 years ago with the grounding work of Ursula K. Le Guin and Donna Haraway. The first wave of feminism evolved into a second wave with the likes of Judith Butler and Karen Barad into the Cyberfeminists movements of the late 90s.

In 2015 a group of thinkers wondered, what if we took accelerationism with all its flaws and brought it into a feminist perspective; The Xenofeminist Manifesto was born [2]. Incepted by Laboria Cuboniks, it represents an attempt to articulate a form of feminism fit for the 21st century. A new wave of philosophical attempts to articulate a feminist view for gendered bodies to merge with the sciences and technology.

Described as a pocket colour manifesto for a new futuristic feminism, the book advocates for gender, race, class abolitionism, anti-naturalism politics, and the reappropriation and repurposing of technology. It explores “both tyrannical and emancipatory possibilities of technology, seeking to uproot forces of repression that have come to seem inevitable – from the family to the body, to the idea of gender itself.”

There is nothing that cannot be studied scientifically and manipulated technologically. It is a fact that we are already inside a giant technological accelerator, and we need to keep adjusting accordingly. The manifesto also sees that Accelerationism can be understood or deliberately reinterpreted as engaging with a process of repair. A reparative Accelerationism gives xenofeminism something to salvage.

Heir of these new feminist movements is XEN, a platform and collective based in Berlin for discussion/experimentation focusing on intersections of queer, gender, and feminist studies with digital culture & tech. Programs consist of performances, screenings, and panels that revolve around contemporary art and philosophical-theoretical themes such as posthumanism, xenofeminism, cyborgs and prosthetics, surveillance technologies, and virtual reality. There was a discussion of an article by Karen Barad as part of this project, where she talks about matter and quantum physics and speculates on the potential queerness of interactions between particles.

And how do gender studies integrate with digital realities, video gaming, and virtual reality? Micha cárdenas combines all of them for her transgender studies. Cardenas is an artist, theorist and poet working with algorithms and poetics of trans people of colour. The Sin Sol / No Sun (2018) project is an augmented reality game where a trans person of colour from the future tells the story of the trans community and how to interpret climate change. Cárdenas provides these extended realities as a safe place for the trans-Latina community.

The Hyphen-labs collective also talks about current race and gender issues. Within their practice, they question and challenge both the gender divide and the lack of representation of Black, Latina and Middle-Eastern women in the tech field. Their project NeuroSpeculative AfroFeminism (2017) is a futuristic transmedia exploration told through emerging technologies and VR of the physical world blending with the digital.

The project NeuroSpeculative AfroFeminism invites the viewer into a futuristic neuro-cosmetology lab, where it blends the local narrative of the beauty salon with science fiction. By way of the so-called “transcranial extensions” (known as Octavia Electrodes, in reference to author Octavia Butler) and an Oculus Rift VR set, the audience is invited into a digital environment, where the restrictive and reducing narratives currently set for women of colour can be explored and expanded and, hopefully, re-written.

We’ve shown while some of the aforementioned artists, such as Ben Grosser, interpret our extended digital personalities as the way we interact with social media platforms, others like Lawrence Lek and Jakob Kudsk Steensen are more focused on the ability of digital technologies to manipulate reality and create other planes of digital existence. Others like Micha cárdenas, Hyphen-Labs, and XenoEntities attempt to construct a more intimate and kind relationship with technology that reveals insights into the future from new perspectives on gender and race.

Epilogue

What can we learn from the fact that now the physical world as we know a mere technological trick can replace it? One possible answer comes from Marina Abramovic and ORLAN, who, both in their 70s, have recently created new digital artworks reinventing themselves once again.

Both artists have evolved in their practices to embrace new digital technologies, and in doing so, they answer the question in two different ways. Marina Abramovic, for a show at the Serpentine Galleries, created an alter ego using mixed reality in collaboration with Tim Drum studio. In “The Life (2019)”, The artist instead of being there performing with the audience as in previous works, interacted with them by showing up as a big hologram.

On the other hand, ORLAN’s approach to these digital technologies embraces the previous body performances that made her a key artist in the last decades. For the exhibition Artists & Robots (2019) at Le Grand Palais in Paris last year she created a humanoid (which she called the ORLANOIDE) who looks and acts somewhat like her. In this installation, the robot speaks, dances and sings with ORLAN’s voice and multiplies itself using mirrors, creating a real visual show and a deep learning theatre. The orlanoïde chats with the flesh ORLAN using two HD displays, three cameras and a presence detector.