Text by Juliette Wallace

Art Laboratory Berlin, one of the city’s first dedicated art/science spaces, never fails to produce fascinating, stimulating and often rather special exhibitions. Fermenting Textiles is no exception. An intimate portrait of an action both gestural and practical, the act of mud-dyeing fabrics opens a dialogue across continents and ages – from West Africa to Japan, from the distant past to the near future.

A small, airy space just off Prinzenallee, the cross-disciplinary gem of Art Laboratory Berlin has been around for just under twenty years. It’s run by Christian de Lutz and Regine Rapp, both of whom are tangibly passionate about their work which is invariably reflected in the exhibitions themselves which tend to bubble – sometimes literally – with excitement and ideas. And none more so than this one.

Fermenting Textiles: Weaving Together Traditional Craft, Anthropology, Microbiology, and Art is, like its subject, both delicate and earthy, drawing from the ground whilst accessing the lofty world of vision. It uses history, science and art to bring to a general public dyeing but relevant traditions in the field of fabric colouring which could suggest an antidote to fast-fashion. The result is an elegant show that demonstrates a considered respect for cultures and their historic methods and hope for what could come on a global scale. And it must be said that the rare luxury of hope is not to be taken for granted in this day and age…

What is immediately apparent upon entering the space is that something different is being displayed. Not just a method and product but a well of tradition, culture, mentorship and cross-cultural – even cross species – inspiration. Living matter is at the project’s core – that which gives the mud its colouring (and other) power. As microbiologist Regine Hengge, one of Living Matter’s protagonists, states: mud means soil and soil means a certain microbiome. This is a unique inter- and trans-disciplinary research and exhibition project that puts active matter at the centre.

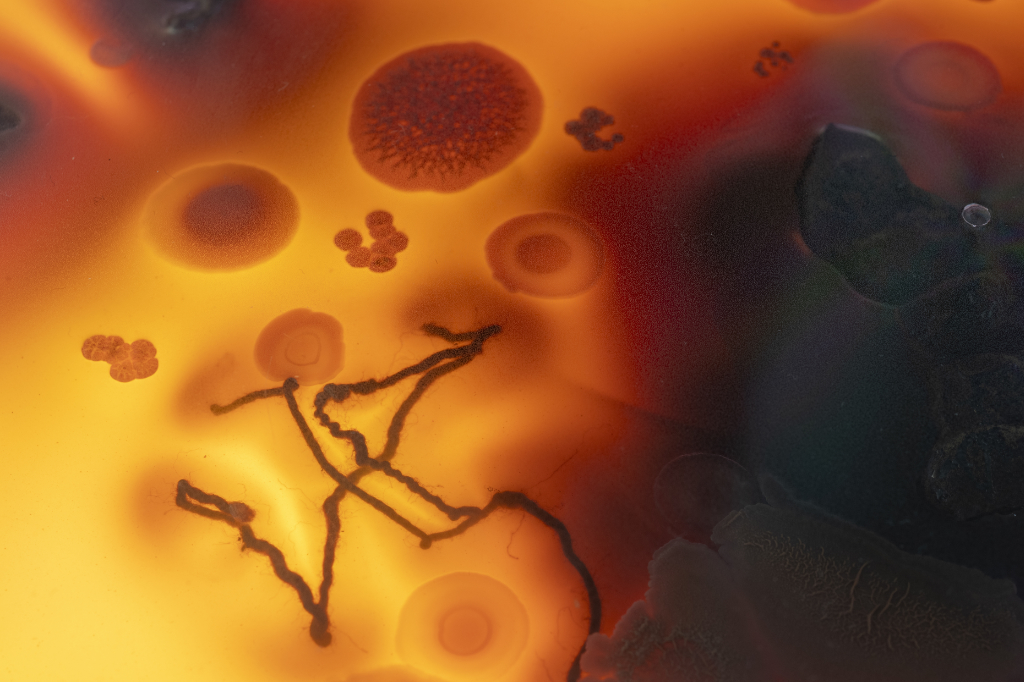

Through the shop-front style windows of Art Laboratory Berlin, the viewer catches a glimpse of various articles, all various shades of brown/black. The homogeneity of the colours is contrasted by the variety of objects which range from t-shirts and scarfs to clay pots to petri dishes and microscope photographs to video display screens to a large spinning fabric sculpture shaped like the billowing skirt of a Whirling Dervish. From the outside it’s not altogether clear what the subject matter is but there’s something about the fabrics that give a little bit away.

Once inside the focus of the show starts itself to come into focus. It becomes clear that the pot on the centre plinth, surrounded by a scattering of petri dishes displaying the components of the vessel’s contents, is a dyeing pot and that the materials and items of clothing hung around the room are demonstrations of dye in action. Upon further exploration the dynamic of the space is revealed: the room has been split in two, with one side dedicated to Vouwo dyeing in Burkina Faso, West Africa and the other to Dorozome dyeing in Amami Oshima, Japan. In fact, the whole exhibition is the product of a two-pronged research and art project helmed by Adama Séré, Laurence Douny and Regine Hengge on the Burkina Faso side and Pauline Agustoni and Satomi Minoshima on the Amami Oshima side.

I am lucky enough to have the artists, scientists and researchers there in person alongside Christian and Regine [1]. Every involved party member is practically buzzing with passion and excitement in a way that is contagious, endearing and a little nerdy. It’s a beautiful thing to see. There’s also a clear camaraderie between them which Regine highlights in her opening speech stating: it’s always a pleasure to work with people but there are some people you just know you’re going to work with again. I’m very proud of this project!

Laurence Douny and Regine Hengge take the reigns for the Burkina Faso presentation, explaining the complex bimolecular soup that makes up the mud and describing the method of colouring. Iron, sulphates and bacteria all play their part (as they did all the way back in the Middle Ages) whilst the humans involved, such as master dyer Adama Séré, have the role of understanding and harnessing this living matter. The treatment of the soil is fundamental – it must not be agitated or introduced to foreign bodies (a dead gecko once sent the whole process awry) and so the art of mud dyeing is revered and passed from generation to generation. The same is true for the Japanese Dorozome dyeing which uses a similar mud with the equal bio-molecular properties (although this process introduces local tree bark to the lengthy process which takes eighty-three steps to achieve the unique black that they’re after!).

The mud’s almost magical qualities – health and aesthetic – mean that it is a precious (albeit not financially) mixture. As well as its dyeing capacities it can be used for everything from tummy upsets to skin rashes which makes the wearing of it beneficial. It is particular fascinating to hear that Dr Hengge, whilst witnessing a batch of disturbed mud, noted what she recognised as a bacterial membrane – an almost impenetrable bacterial state that causes great obstacles for doctors and scientists. She learned from Adama Séré the best way to manage it through his and his culture’s own experience.

The prospect of future applications of this knowledge is exciting. Not only does the research team want to find a way to bring awareness to these existing and unique dyeing techniques but they also want to apply the logic of this clothing to combat our detrimental fast-fashion. The sustainability of the material after being exposed to the dye (it’s proven to last longer as a fabric once coloured) and the positive health benefits of wearing the clothes both act as inspiration for a possible new approach to fighting the throw-away fashion culture that currently dominates the world. Regine Hengge has even made her own material with her own pattern, demonstrating this in practice with her “Multiples”(she calls this the “shirt to shirt” journey).

Thoroughly excited beyond what she expected she could be by mud, this author hopes that future generations begin to apply the special skill of mud dyeing and its properties to a larger scale whilst, of course, crediting the origins and original practitioners of the methods.

Fermenting Textiles: Weaving Together Traditional Craft, Anthropology, Microbiology, and Art is open until 6 July, and Regine Hengge and Laurence Douny will give an exhibition talk on 15 June at 3 p.m.