Text by Robert Barry

The city of Culiacán in north-western Mexico known for its hot summers, the beauty of its natural surroundings and a boisterous sinaloense culture. But it’s rare to find the place rhapsodised in the pages of the Lonely Planet. Unlike Guanajuato or sun-baked Cancun, Culiacán has a gun problem. When Mexican law enforcement arrested drug lord Ovidio Guzmán López, son of the notorious Joaquín “Chapo” Guzmán Loera, in 2019, hundreds of sicarios blockaded the streets for over four hours, setting off numerous gun battles throughout the city, resulting in multiple fatalities.

Cartel foot soldiers were seen loaded with AK and AR15 rifles, M2-type heavy machine guns, belt-fed machine guns, at least one M72-series shoulder-fired rocket launcher, and multiple smaller handguns. This was not the first time the city had exploded in violence. In 2008, a raid on a home believed to be sheltering weapons and drugs resulted in the death of seven police officers and injuries for four more. Seven AK-47 rifles were found and confiscated, along with dozens of ammunition clips. When artist Pedro Reyes was invited to do a project in the city in 2007, he wanted to do something that would make a difference – and he wanted that difference to be measurable.

It’s unusual to think of works of art in terms of clearly quantifiable results. Something about the idea feels like antithetical to the kind of free play of the imagination we tend to associate with genres like painting and sculpture. But Reyes was inspired by conversations he had with Harvard humanities professor Doris Sommer. Throughout the Americas, creative culture is a vehicle for agency, Sommer wrote in a paper from 2005.

The appropriate question about agency is not if we exercise it, but how self-consciously we do so; that is, to what end and what effect. Reyes began to ask himself, is it possible to make art accountable? as he told me over a long Zoom call in July. When we are used to thinking of aesthetic impact as something purely symbolic, the question of how to measure that impact becomes vexed. But what if it wasn’t?

Sommer introduced Reyes to Antanas Mockus, former mayor of Bogotá. Twice elected to the Colombian capital’s mayoralty, Mockus had already led a storied political career and, a few years later, he would come within a whisker of becoming the world’s first green party president. But Antanas Mockus is no ordinary politician.

A former maths professor and philosopher who once mooned his students to stop them from rioting and used to teach civics classes in a superhero cape, his two terms in office were characterised by a series of spectacular experiments in social organisation. He once hired a troupe of 420 mimes to stand on street corners lampooning any traffic violators, reasoning that Colombians were more scared of ridicule than a few points on their licence. It worked. He also cut homicide rates by 70%.

Reyes worked with local authorities in Culiacán to organise a weapons amnesty. Residents were offered coupons, exchangeable for household appliances, in exchange for their guns. In the end, some 1,527 firearms were collected, piled up, and destroyed. The crushing of the weapons was a performance in itself. People gathered to watch as this massive pile of steel and chrome was crushed flat by steamrollers in a public ceremony. But Reyes knew that couldn’t be the end of the story. It wasn’t enough simply to destroy the weapons; he wanted to make something of them. To find the next piece of the puzzle, he turned to the filmmaker Alejandro Jodorowsky.

Alongside his storied career as the director of such cult films as El Topo, The Holy Mountain, and Santa Sangre, the Chilean avant-gardist had long pursued a sideline in more esoteric pursuits. In 1995, he published a book detailing a form of therapy of his own devising, Psicomagia: La Trampa Sagrada (‘Psychomagic: The Sacred Trap’).

In Psychomagic, Reyes explained to me, you enact a ritual – often you go through an intentional traumatic process where you face your fears. If you’re afraid of not being a good filmmaker, he would tell you to make a film that is badly written, badly acted, badly lit, and then invite your friends, do a screening and everyone will laugh at your bad movie. Then you will be cured. You have to stage your fear and overcome them. But the ritual doesn’t end there. Having made you confront your fear, Jodorowsky offered one further prescription: to plant a tree.

I asked him, Reyes continued, why there is this idea of planting in psychomagic, and he told me that, after a traumatic process, you have closure, but it’s good to open something new. That way, your mind’s at ease. It’s not dwelling too much in the trauma but in the new cycle that you’re opening.

Reyes’ 1,527 steamrollered guns became 1,527 metal shovels which would be used to plant 1,527 trees all over the world. Any time the work is shown at a gallery, Reyes insists on a commitment from the institution to do a tree-planting. In this way, the shovels become catalysts – for an activity that local families can get involved in and enjoy participating in, but also for a small but positive tangible change to the global environment. The destruction of the weapons reminds you of all the trauma and all the suffering, Reyes says, but with the act of planting, the tree becomes like a living monument that you will see grow. Reyes likens the process to a form of alchemy: the transformation of something base and corrupted into gold.

The project was so successful that soon other municipalities around Mexico got in touch, asking Reyes to repeat the trick. When the local government in Ciudad Juárez called, Reyes still hadn’t used all the shovels made in Culiacán, so I did not want to commit to planting more trees without having finished the first mission. Keen to maintain the participatory element of the first project, he turned to music.

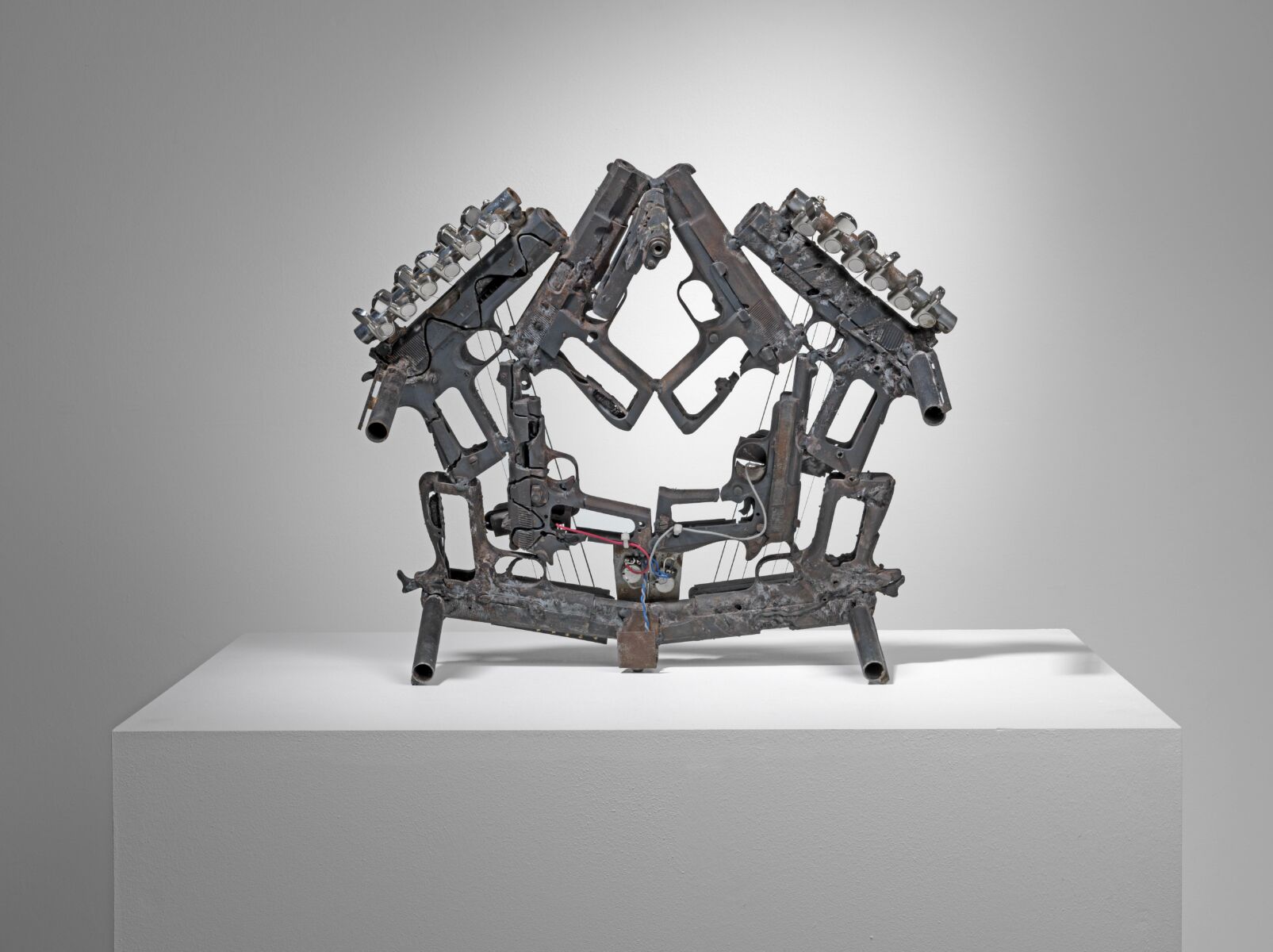

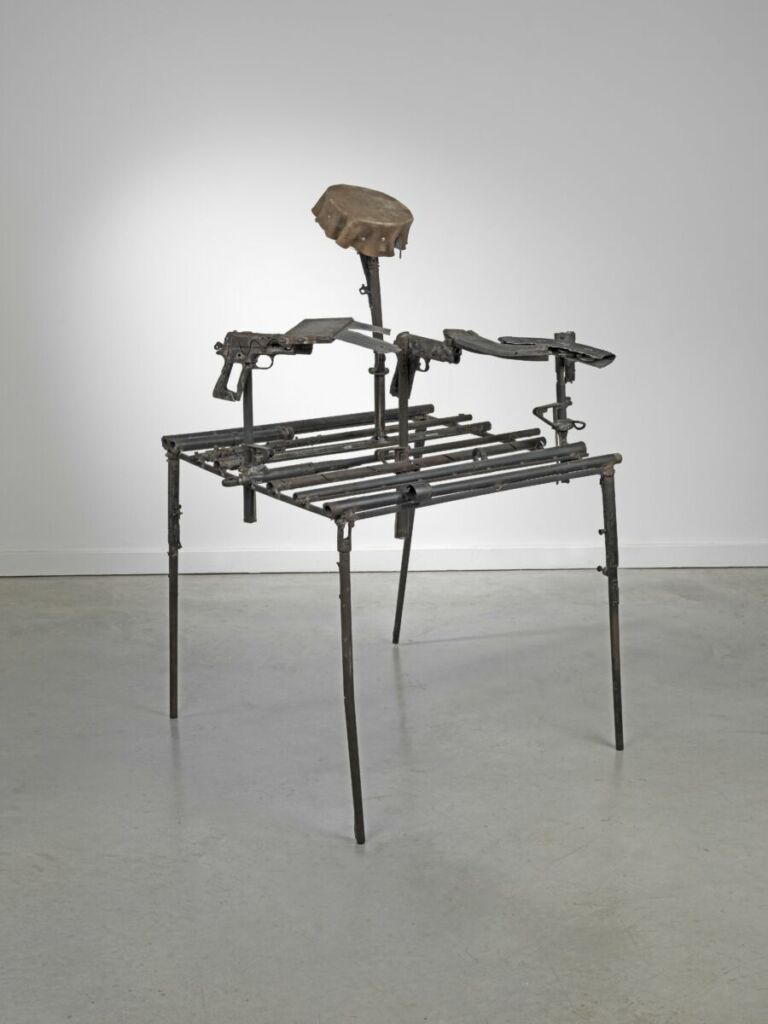

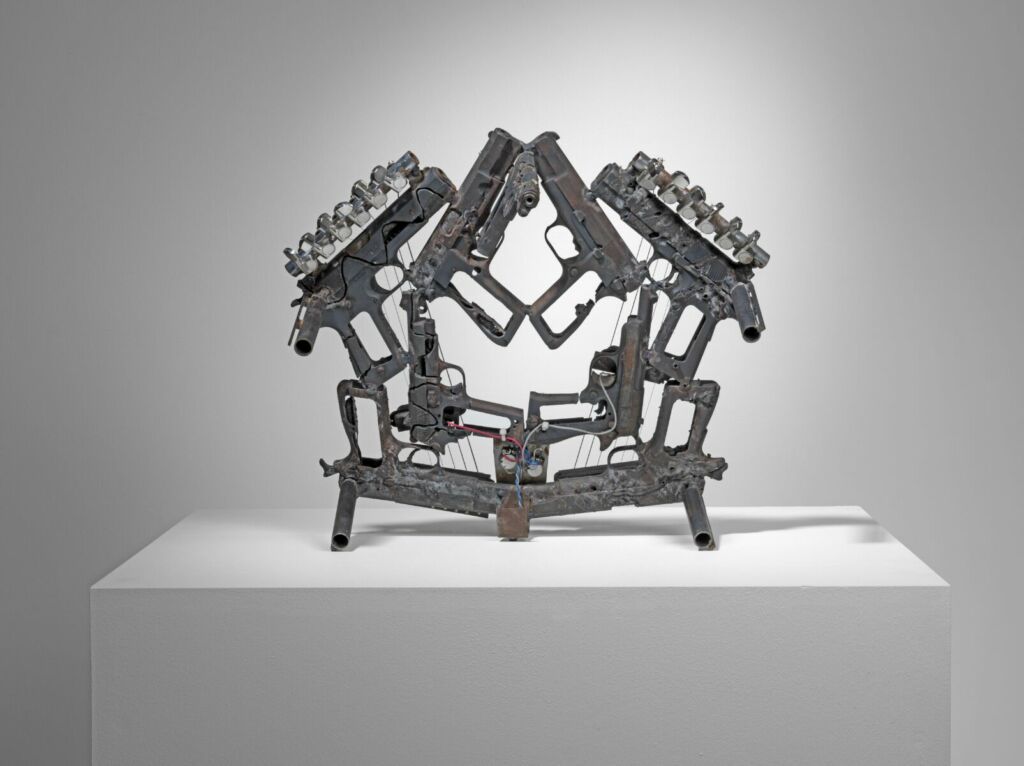

Music connects a whole group by this experience of sound, he explains. It’s the opposite of what guns do. There is a change in polarity because weapons are the rule of death and fear and music is the rule of empathy and trust and enjoyment. Working with a group of musicians and blacksmiths, he took even more crushed-up firearms and turned them into flutes, gongs, guitars, and violins. Now, along with the tree planting, Reyes’ exhibitions will often come with a concert, too.

When I spoke to violinist Laura Ortman, who played one of Reyes’ violins at a performance at SITE in Sante Fe, New Mexico, just this past January, the first thing she recalled about the instrument was its weight.

It’s incredibly heavy, she said. I had to have them make a stand for me because even just holding it for that amount of time was taxing on my wrist. But once she got the hang of the thing, she found herself digging deep into her own family history to find a way of communicating through the instrument. I’m a White Mountain Apache, originally from Arizona, she said. I felt like I had to reach back to generations before who were using weapons to fight off intruders. It went way back for me. And then I tried to go forward.

Her performance veered between explosive, violent sounds made by running the instrument through a battery of effects pedals and far more serene sounds with more traditional harmonies trying to make peace with it, as Ortman put it to me. In a recent talk for the Oto Sound Museum, Reyes said the concert gave him “goosebumps”. Ortman recalls seeing people in the audience crying.

I’m not a composer, Reyes told me. I don’t know how to play any instrument. But he relishes what he calls the surprise and joy of working with musicians … this cross-pollination between different artists and art forms. And the Disarm project carries on. Reyes continues to collect guns and to build instruments and to seek opportunities for collaborating with musicians. When you adopt a cause, he said to me, you can not leave it. Only last month, he found himself in Vancouver, where he had the opportunity to visit a tree that he had planted with one of the first shovels from Culiacán over ten years ago. It’s very satisfying, he said, to see how it has grown.

Art and war have long shared a secret history. The German media theorist Friedrich Kittler reminds us that Albrecht Dürer’s pioneering work developing linear perspective went hand in hand with his studies in ballistics. Philosopher Paul Virilio saw in the revolving barrel of the gatling gun the model of a movie camera’s magazine. But where most sculptors tend to treat their work as if it were aloof from such violent genealogies; Reyes’ Disarm instruments confront them head-on. His flutes still look like rifles, with holes drilled at intervals down the length of the barrel.

The bodies of his guitars retain the shape of ammunition magazines. Ortman recalls that the violin she played still had wires and sharp screws sticking out from the ends that had to be filed down and cushioned over before she could place it between her neck and chin to perform in order to avoid being stabbed by her own instrument. They are never separable from their own violent origins.

Reyes told me he wanted people to walk from his concerts feeling like they had witnessed the celebration of a victory over these pieces of metal that we have always been afraid of. I want to transmit to people the hope that transformation is possible. We don’t have to surrender to this. But most of all, in laying bare the origins of his instruments, he wants to turn people’s attention to the origins of the weapons themselves.

A lot of times, the blame for gun deaths always falls on whoever pulled the trigger, he told me. So the people who make the guns are always off the hook, and these are industries that are working in the shadows. You never know much about them and the only thing that they cause around the world is death and suffering. There are enough weapons in the world. We could stop the production of weapons altogether, and the world would only be a better place. The reason we are not able to do this is because there are a few people who are getting rich. My hope would be to stigmatise gun makers, for them to be seen for all the evil they cause.

Pedro Reyes, Sounds of Disarm, is at Oto Sound Museum until 8 August 2023.

For his projects Palas por Pistolas and Disarm, Mexican artist Pedro Reyes has been gathering up guns and transforming them into tools.