Text by Frances Whorrall-Campbell

A Little Peace and Quiet’, a 1985 episode of the cult television series The Twilight Zone, ends with the image of a nuclear warhead hovering in space [1]. Penny, a harried housewife with the ability to freeze time, is facing a terrible dilemma: keep the clocks stopped or start them up once more, condemning the planet to certain destruction. The missile presides over Penny’s impossible situation like an absurdly prescient augury, the stomach-jerking irony of which only deepens when we see that the blast site to-be is a cinema screening Dr Strangelove and Fail Safe [2].

The drama and humour of suspended animation are evident in TAKIS: Sculptor of magnetism, light and sound, on display at the Tate Modern until October 27. This is not the star show of the season at Bankside; that title would be claimed by Olafur Eliasson’s confection of coloured lights and mind-altering fog. This is a shame because although Takis’s works are more contained (and in many ways more old-fashioned) than Eliasson’s immersive interventions, he shares a similar interest in the relationship between art and technology, and a sensitivity to the viewer’s bodily experience.

The exhibition takes in Takis’s oeuvre from the 1960s to the present, leading the viewer thematically through the artist’s use of magnetism, electricity and the human body to generate kinetic, illuminated and musical objects. The presentation closes with his most recent work, a thunderous (and quite literal) exploration of the concept music of the spheres. Since Takis’s death during the show’s run the large sculptures gathered here have taken on the quality of a mournful memorial.

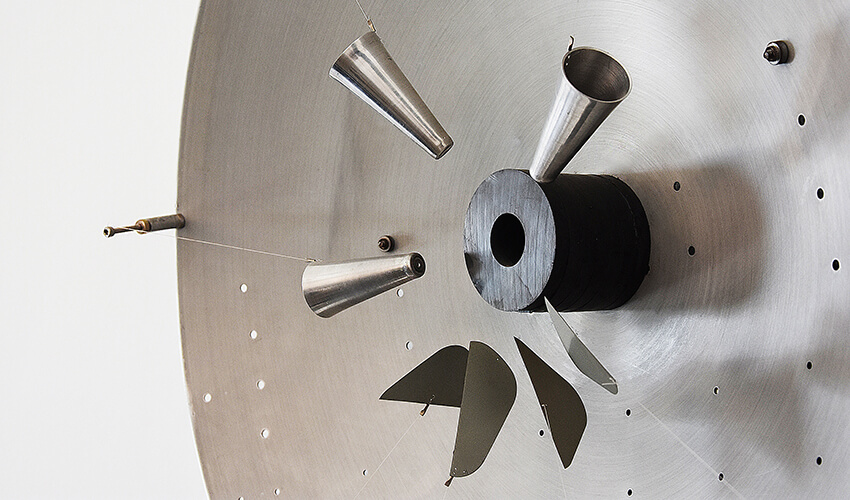

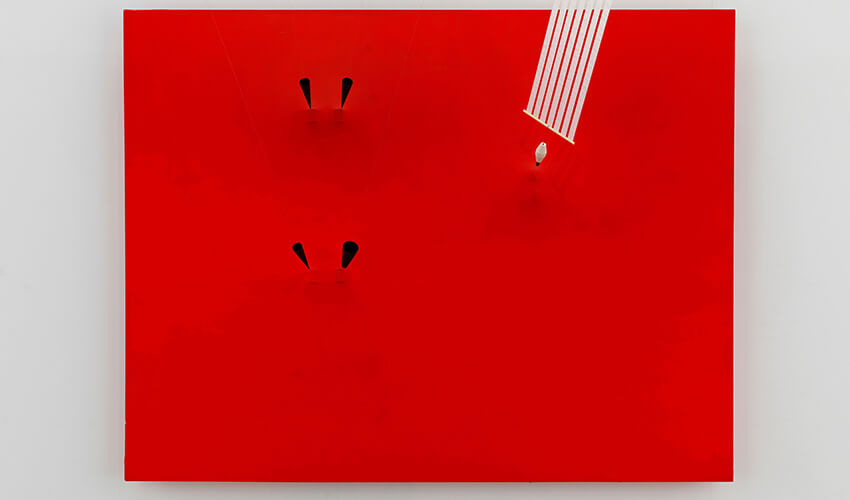

The works on display at the Tate are both electromagnetically and emotionally charged. Coils of copper wire exert their invisible power on metalware of various sizes; from pins and nails to rather more heavy-duty cones and spheres, tethered by improbably thin fishing wire. Some of these shapes tug at magnets secreted behind painted canvases; menacing armatures poised to pierce the fabric. I wait for the surface to burst, reminded of John Hurt’s distended chest in Alien.

But this arrested momentum also gives rise to a clownish humour. The bent nail in Magnetron (1964) swings towards its attracting pole with something of the jouissance of the young woman in Fragonard’s Swing, her foot outstretched as she reaches the peak of her trajectory. There is a sense of lightness and movement, but there is also something inherently funny about watching (or imagining) objects flying through the air.

According to Brian Dillon, anthropomorphised objects have a particular place in slapstick [3]. Objects that appear sympathetic to the travails of the human condition provoke the childish joy of recognition. I felt an immediate kinship with a small Telesculpture whose three pins were waggling themselves helplessly at the central coil, their neurotic jiggling interspersed by short breaks, as though from fatigue.

When I visited, one sculpture was ‘having a rest’ (in the cutesy language the Tate employs on its signs when a kinetic work breaks down or is stopped for conservation purposes) – a coquettish or tongue-in-cheek departure of the work’s spirit from the exhibition space, a fact which draws attention to the object’s soulful qualities in the first place.

But if objects are humanised, humans are also objectified in both Dillon’s theory of slapstick and Takis’s works [4]. On the 29th November 1960 at Galerie Iris Clert the Greek artist launched his friend, the poet Sinclair Beiles, into (the gallery) space. The poet was momentarily suspended in the air by magnets: a temporary insertion of himself into one of Takis’s dynamic assemblages. After his brief flight, Beiles read from his anti-nuclear poem Magnetic Manifesto (composed specially for the occasion), making explicit his transformation into one of the artist’s kinetic sculptures, albeit one with a voice to exclaim his object status.: ‘I am a sculpture. There are other sculptures like me. The main difference is that they cannot speak’ [5].

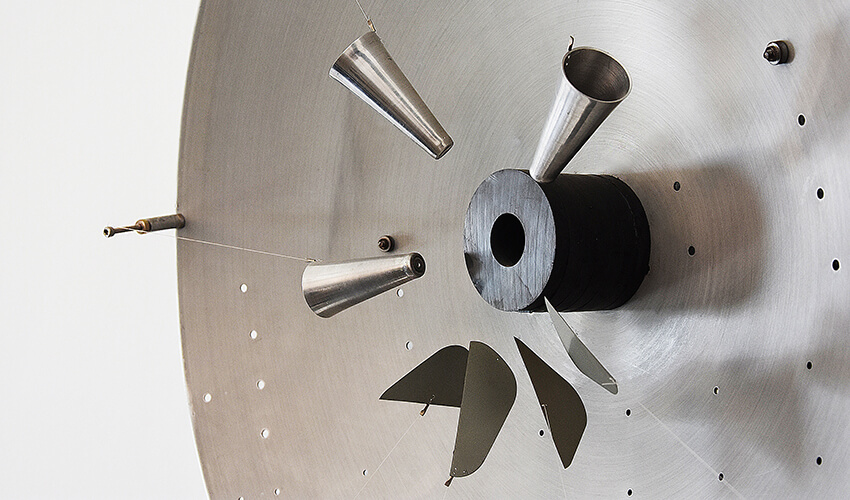

Right: Télélumière-No 4, Takis (1963)

And if the poet is an artwork, he is an extremely dynamic one: full of explosive energy and charismatic wit. This combination of an outward-facing propulsive (or repulsive) force with magnetic charm is characteristic of Takis’s devices. The viewer is brought into the work even as the objects themselves repel each other. Ballet Magnetique (1961) stages a pas de deux between a small white ball and a black lozenge over a magnetic coil.

The pair swing and skip around this central column, occasionally pirouetting in its field before spinning away, only to be brought back into its orbit. It is hypnotic to watch: I spent a long while trying to figure out if the shapes were actually repelling each other, or if they were just positioned in such a way so that they would never touch, only glide gracefully past one another.

The sculpture had to be activated at regular intervals by an attendant in white gloves. I waited in anticipation for her to reset the hanging objects and set them off in their dance once more. Activation as a mode of engagement sits somewhere between the passive viewer in the gallery and the active body of Sinclair Beiles. The stewards are both part of the works and watching them: alternating between being a necessary accessory and frivolous observer. This dynamic is particularly evident in the final room which gathers sculptures from the open-air theatre in the Takis Foundation. In London as in Athens, these objects are arranged around a central gong which is made to sound at regular intervals.

The pounding of the hammer swinging against the beaten-metal disk (and the electronic buzz of a giant sphere as it grazes an amplified wire which provides tuneless accompaniment) are startling, grating on the ear: loud and disruptive noises in an otherwise contemplative space. They are a call to pay attention – to look and to listen. Takis stated his intention to make invisible forces visible, and the sounds he conjures up certainly do this, not just on the level of their electromagnetic origin but as components of artworks. The racket makes the viewer hyperaware not only of the sculpture but of the attendant. People whose presence in the gallery generally goes unnoticed suddenly find themselves centre-stage (this new fascination is attested to in the notices forbidding photography of the stewards at work).

Takis was a founding member of the Art Workers’ Coalition, formed in January 1969 after the artist forcibly removed one of his works from a show in the MoMA, New York. The curator Pontus Hulton had failed to consult Takis on his choice of Teles-sculpture (1960) from the museum’s permanent collection for the exhibition The Machine at the End of the Mechanical Age, prompting the artist’s own protest and instigating wider action by a certain section of the artistic community in New York. Whilst the AWC largely represented the grievances of artists rather than museum staff, it demonstrates Takis’ critical interest in the context of his works.

But the real concern that emerges in this exhibition is with the military-industrial complex and the myth of technological and scientific neutrality. Much of the work in the Tate was produced at the height of the Cold War. By launching Beiles in The Impossible: A Man in Space (1960), the artist was directly parodying the current competition between the USSR and USA. The arms race had blasted off: the struggle between the two superpowers was now as much for space-bound satellites as satellite states. The potentially deadly consequences of weaponizing Earth’s orbit was played out in the piece. Beiles cast himself as a hydrogen bomb visiting the ruins of Hiroshima to watch Takis make another sculpture from atomic technologies: I would like to see all the nuclear bombs on earth turned into sculptures [5].

In his junkyard aesthetic, cobbled together from scavenging military surplus and discount electronics stores, Takis dredges up the wrecks of this complex, imagining a future in which this technology was obsolescent. But whether these are the quaint amusements of a future utopia (a kind of peacenik retro-chic), or desperate post-apocalyptic inventions, it isn’t clear. What is clear is how they sit now: in the halls of one of the world’s premier galleries of modern and contemporary art – an institution previously funded by BP and with a poor (but arguably improving) record of showing artists who are not white and/or not male.

In this context, Takis’s works fall short of providing any radical contemporary commentary. Real critical damage is blunted: they hover above the point but are never able to strike the final blow. It is a comprehensive survey, but I miss the lively and provocative edge of the earlier protests. In his later years, Takis seems to have turned away from politics, producing works whose disruption is an exploration of the movement of the heavens rather than a comment on life on earth.

This work is too easily absorbed into the comfortable narrative of the male minimalist or conceptual artist that has dominated museums like the Tate until recently. In this way, the exhibits are rendered static, even though they move, it is as though they are in a vacuum: the warhead above us is disarmed, comic but essentially unthreatening.