Words by Lula Criado

Hanna Haaslahti is a media artist based in Helsinki (Finland). With a background in photography and set design, her work encompasses interactive installations, projections and experimental film in the fields of visual arts and new media. The conceptual frame of her work lies at the heart of Gestalt psychology and computer vision.

Gestalt psychology is based on the deconstruction of the entire situation into its elements. So ‘Why do symmetrical, regular, simple and orderly tend to command our experience?’ Hanna asks. On the other hand, computers can track gestures, facial expressions and the movement of people, so gestalt psychology is used in computer vision to make computers see the same things as humans do.

Gestures, movements, shadows, light and human interaction are some of the central axes of Hanna’s creative universe, which involve viewers in visual metaphors. Past projects, White Square (2002) and Space of Two Categories (2006) take the shadow as a starting point to create interactive spaces. The shadow is our alter, mystery and immaterial ego that accompanies us through our entire lives.

In White Square, electronically generated artificial shadows with a computer program alternate in a white square with the real shadow of the viewer. The viewers find themselves surrounded by multiple real and unreal shadows. In Space of Two Categories, the interaction between human-computer takes place on a screen. The shadow of the visitor interacts with their white child shadow creating a space of two categories.

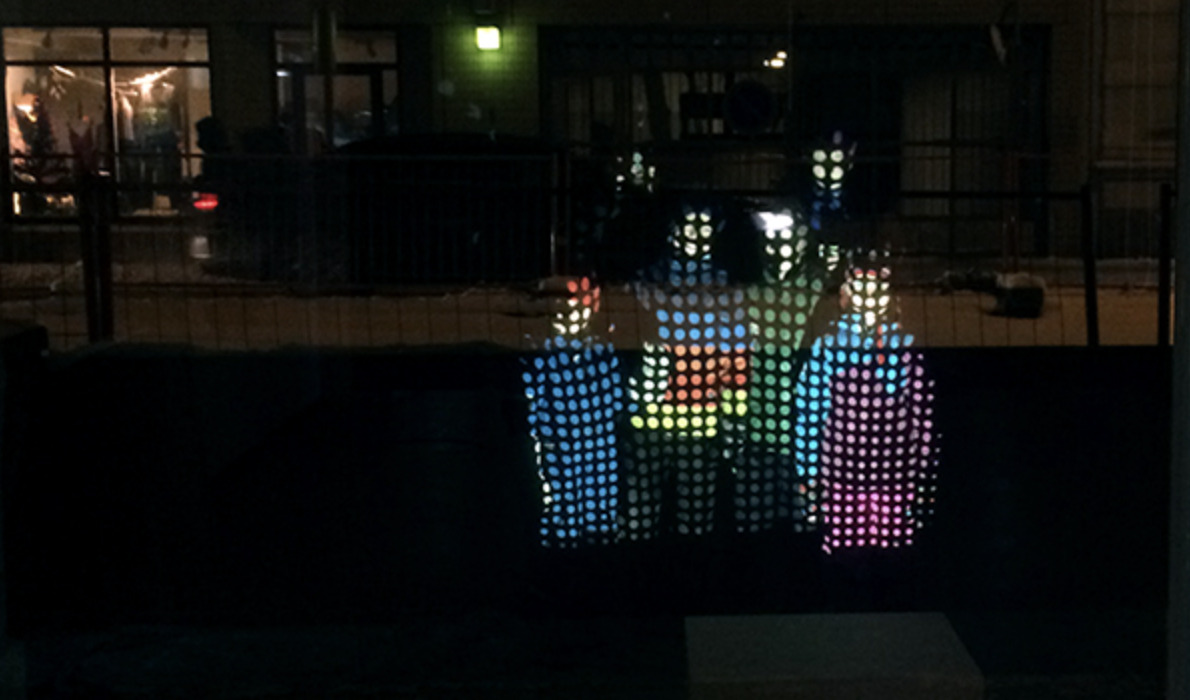

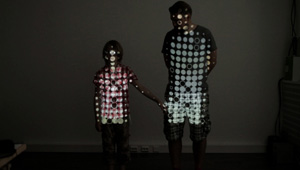

In one of her most recent projects, Habitus (2013), Haaslahti builds a journey in which she experiments with one of the laws of Gestalt psychology, the Laws of Organization in Perceptual Forms, defined by Max Wertheimer. Habitus is a thrilling performance in which the audience’s bodies are used as a canvas to show the Gestalt principles of figural stability.

Hanna Haaslahti uses the gesture as an artistic process and monitors the movements of the people’s shadows. The shadow is an extension of the body that, according to Jung, may refer to the unconscious aspect of the personality; however, in Haaslahti’s works, the shadow takes a new definition: a metaphysical metaphor about alternative realities.

‘I think we exist as beings somewhere between our bodies and their shadows, and everything extends and floods beyond the physical boundaries.’ Haaslahti told us.

The main themes in your interactive installations connect art and technology to explore the relationship between people, space and projection. Could you tell us a little bit about your background? What drew you into working in the intersection of them?

I was always fascinated by how physical bodies continue in their shadows. I think we actually exist as beings somewhere between our bodies and their shadows, and everything extends and floods beyond the physical boundaries. When I was a child, I thought that shadows lead somewhere, that they are actually gates. It was fun to jump into someone’s shadow, a strange kind of private area.

When I was in high school, we were a group of four people who would do all kinds of urban light interventions and projections in our city, Pori, a small town on the west coast of Finland. That was in the early 90s. After that, it just got more and more interesting with computers becoming available for art students. The conceptual frame of your artistic practice is to explore Gestalt psychology. For those whom the term may sound unfamiliar, could you tell us a little bit about the intellectual process?

Why do symmetrical, regular, simple and orderly tend to command our experience? I´m interested in the Gestalt theories of perception, which explore what happens in our senses before the rational mind kicks in. Our senses organize percepts into impressions for our brain to make decisions upon. All humans seem to have similar gestalt controlling their senses.

For example, if two people are seen standing close to each other in the crowd, we sense that they form a group, although they might not have anything to do with each other. We like to make rules and assumptions to simplify the chaos of everyday experience. And then test and force these rules on new sensations. Sometimes it works, but sometimes not at all. This confusion between our interpretation of the world and the world itself is a very interesting area for me.

How people respond to multiple stimuli in a digital environment beyond the touch of a screen or button is one of the questions in this ‘hyperconnected’ 21st century. What reaction did you expect from the people who participate in Habitus, and which feedback did you get from them?

I wanted to disassemble the communal viewing process and create a situation where instead of looking in the same direction, people would look at each other´s bodies for the artwork, which also requires them to be close to each other and touch. There are so many interactive installations where people are controlling their gestures and visuals projected in front of them, and that was a media art set-up behaviour I wanted to tackle.

People staring in the same direction, as required in church, concerts, cinema etc., act as a protective cover-up action for the real thing, which is strangers coming together and possibly meeting new people. When you mess with the rules of social gaze and try to introduce different kinds of gathering principles, people get confused, and that was the feedback I got from Habitus.

Time Experiment creates an environment in which concepts of digital media, space and time are closely linked to physical performance. In which ways do you think are interactive and digital technologies changing or affecting human behaviour?

It´s difficult to say where goes the boundaries between you and your community. You become a human by other humans, and now the smartphone is in that inner circle of intimacy. With technology comes also the technology of self-constraint. Your emotions have to be articulated and expressed within the limits of a keyboard. Everybody´s not good at that.

Gestures are becoming mainly digital instead of physical, and because of this, people pay less attention to their physical environment. The culture of small communities, which depended on each member of the group for survival, is lost. Now we seek each other´s company for pleasure, and that has, of course, totally different kind behavioural patterns. Some see it as liberation, some as alienation. Perhaps enough alienation is a way to liberation.

What directions do you imagine taking your work in?

Towards a deeper understanding of my craft.

What is your chief challenge of creativity or creation?

Finding my concentration.

You couldn’t live without…

My family and friends.