As what was once considered the technology of some distant, utopian future quickly becomes today’s technology, lines between machine and man can get blurry. We have become increasingly reliant on devices that help us in our day-to-day lives, the mere thought of existing without them may not be unfathomable, but it is undoubtedly undesirable. For example, leaving the house without your phone might leave you feeling a little incapacitated.

Thus, as tech becomes increasingly more integral to humanity, a slew of new interactions arise as communication changes with the technological world. Collaboration is ever-important as the intersections of science, anthropology, culture, and art are multiple. This is one of the many prospects investigated by the STEAM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Art, and Mathematics) Imaging artist-in-residence project at the Fraunhofer Institute for Medical Image Computing MEVIS in Bremen, Germany.

STEAM Imaging was designed by the science communicator Bianka Hofmann and jointly hosted by Fraunhofer MEVIS and Ars Electronica. In 2017 the pilot project was carried out with the mathematician Sabrina Haase and Yen Tzu Chang as the resident artist. The endeavour aims to foster engagement with and ownership of new tech and to encourage society’s participation in the burgeoning STEM world.

Yen Tzu Chang’s performance piece, Whose Scalpel, investigates the interaction between artificial intelligence-guided surgery and the surgeon and patient. We talked with the artist about the intellectual process behind this piece: A perfect example of an interdisciplinary practice I learned from art history is Leonardo da Vinci, who played an important role in the Italian Renaissance and was interested in an enormous range of subjects.

His notes display his amazing anatomy and mechanics research, which explains his creativity in painting, designing machines and musical instruments. I think we can learn from his spirit nowadays, but we are in a totally different situation where we often only major in one field. So, working with people who come from different fields is a good practice. For instance, this project links science and art together by working closely, sharing and discussing with scientists and experts.

Within two weeks of the Fraunhofer MEVIS residency, my heart’s model was scanned by MRI. At the same time, there were lessons for MeVisLab (which is the software, especially for medical image processing and visualization) and many meetings and consultations with different professional scientists. Through those processes, I gradually learned from scientists and built up the idea for the performance. I chose sound as the performance’s medium because it helps create a scene and atmosphere. From my observations, sound plays an important role in medicine.

For instance, the stethoscope! Another state-of-the-art example that inspired me is the video from the YouTube channel of Fraunhofer MEVIS – “Auditory guidance prototype for navigated liver surgery”. The video shows that if the scalpel deviates from the correct cutting path, the device will make a different sound to notify the surgeon.

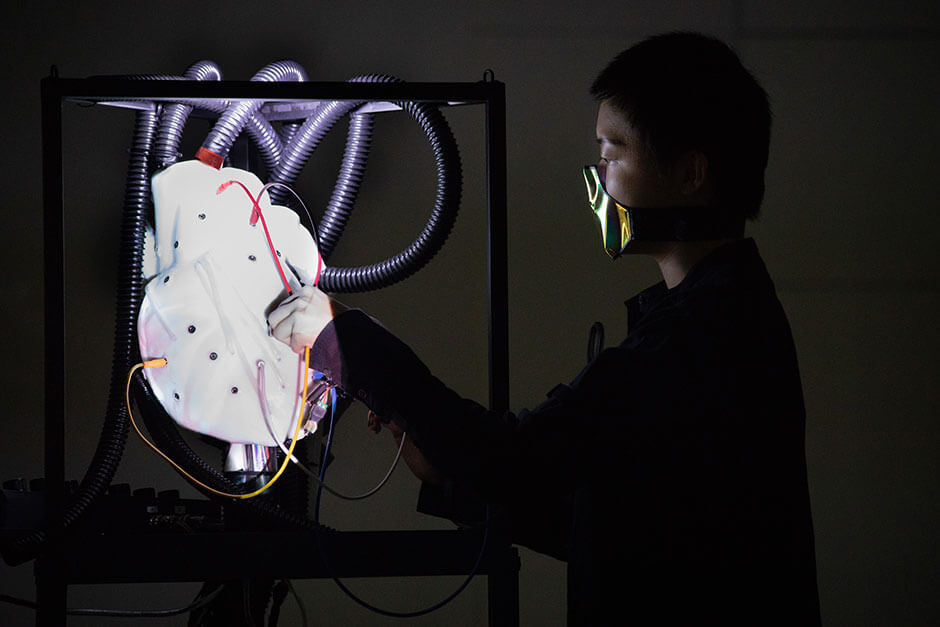

It is for sure that the heart is one of the most important organs for humans, no matter if seen from the perspective of biology or symbolism within society. There is a type of heart surgery called Coronary artery bypass surgery, which is used for treating coronary artery disease by means of creating a new path that enables blood to go through. It inspired me the design of the modular synthesizer. The heart sculpture is designed to interact when the performer plugs in audio cables and bridges connections, letting the signal go through one module to another to produce the sound, just like coronary artery bypass surgery does.

Over the course of her residency, Chang learned to work with MeVisLab, a software platform developed by the institute and often used as the basis for medical computing. During her performance, Yen Tzu Chang acting as the “surgeon”, is guided by robotic surgical instruments and performs “surgery” on a 3D-printed model of her own heart. When asked about the main challenges she faced, she shared some of her experiences: I had a lot of challenges, for instance, fast bringing out the idea, technical problems…, but the biggest challenge was understanding each other. During the project, I met many scientists from different backgrounds, and all of them had different perspectives compared to me in many things.

For instance, I was trying to figure out how to make the medical tool work as an artistic approach, and I consulted many scientists. However, no one had ever thought to use the medical tool like that, so we spent much time discovering its potential and possibilities. And once, in another discussion, I asked if I can have several images of my throat while doing an interview, and it could turn into a video. First, I got a “no” and wanted to know the reason so we might have other possibilities to manage.

We then fell into a long discussion. Later, I realized that it was not because they didn’t want to, but rather because the software application for the MR tomograph, which would allow such an image acquisition, was not available then. However, we still conducted a test scan; maybe it would work out of expectation. Unfortunately, the throat image was blurry and twisted. We could not manage to get perfect images of a constantly moving throat, but no one was upset because we kept patiently communicating and were respectful of each other’s views. Maybe it is a cliché that communication is important to cooperation, but to this project, which combines art and science, it is fundamental and definitely important.

The audience provides an interesting contrast to Yen’s performances, whose reactions can be equally challenging and varied: It’s a hard question because it always differs from audiences from different backgrounds, but I have received a lot of different feedback since “Whose Scalpel” was invited to be presented in Linz, Munich, and Berlin. Audiences from art and music usually focus on the artwork’s meaning, how I arrange sound and combine it with visuals and the process of producing this work when I was performing at the Fraunhofer Berlin.

However, most of the audience have a scientific background and are unfamiliar with media and sound art. They were shocked by the performance and had to ask many questions before they asked the background story of the performance. For example, why is the sound so loud? Is it music? What is sound art? So, I first explained a brief history of sound art and art culture. But no matter what kind of question, it is always good when a question comes out. It means that audiences are interested in the work, and is the beginning of thinking something new for them, and it’s a great chance to interact!

On June 5th 2018, Whose Scalpel was presented within the Fraunhofer Society’s Science and Art in Dialog series at an evening dedicated to The Art of Complexity at the Fraunhofer Forum Berlin location. As Fraunhofer put it, The discussion that inevitably ensued allowed for “a fruitful exchange between art and science.” As boundaries are blurred between programming and people, so do those between disciplines, as art is experienced through the eyes of science, and science is created through an artist’s eyes.

On 9 August, the performance will be presented in London as part of the Music Hackspace programme at Somerset House Studios. The event is curated by Lucia H Chung (who runs the platform Happened) as part of her residency with Music Hackspace, which aims to promote and give visibility to artists from Taiwan working with sound.