Interview by Meritxell Rosell

There was a point a decade ago when the ubiquity of the onstage glowing apple caused something to crack in the electronic musician. The previous decade had seen music technology move at a fierce rate aided by the vastly increased power and stability of laptops, VST software instruments, and flexible performance environments such as Ableton Live moved from simple loop players to seemingly limitless musical studios. Suddenly there was tremendous pressure to live up to these new expectations, and that kind of open-ended system can be paralysing. People downsized and started to fetishise more the analogue synths of yesteryear, but that in itself can lead to dead ends sonically when everyone is using one of a dozen classic Roland, Korg or Moog pieces to create with.

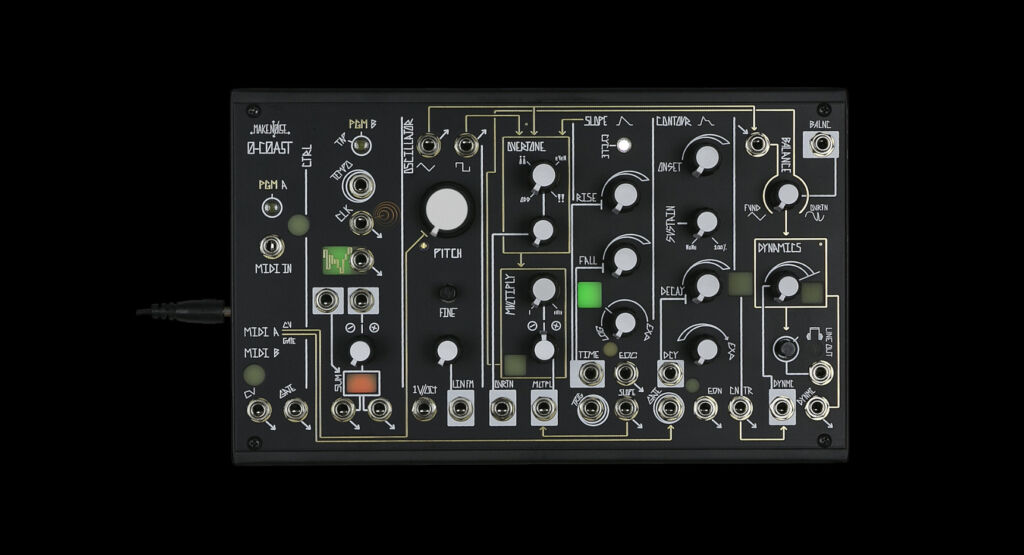

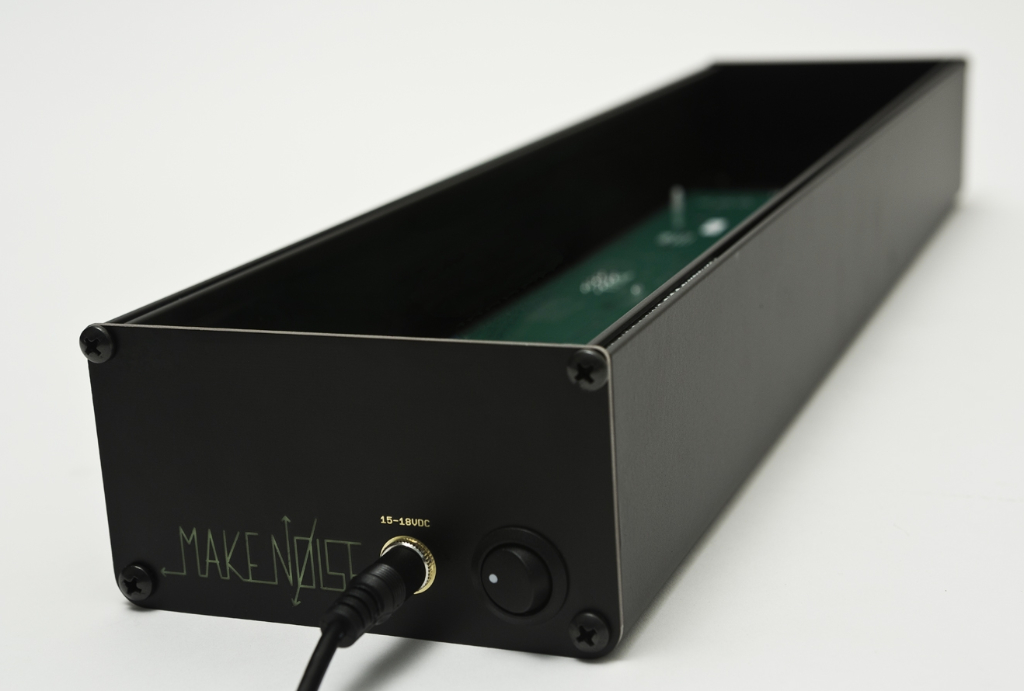

At the same time, there was an explosion in modular synthesis as a cottage industry, with small entrepreneurs creating units in very limited numbers performing very specific tasks in the model of boutique guitar FX companies of the 70s. One of the motors of this explosion was Tony Rolando and his creations for Make Noise.

Rolando founded Make Noise in 2008, the modular synth company which he runs along with Kelly Kelbel in Asheville, USA. Something that started as a small enterprise has developed into a worldwide manufacturer, designing and building some of the most exciting, odd (in most positive ways) modular synthesisers, highly praised worldwide. And last weekend, they celebrated their 10 years in the making with a showcase featuring live performances on Make Noise systems by artists like Bana Haffar and Hypox1a, panel discussions and an installation by Richard Devine.

Delving deep into the world of modular synthesis is almost like falling into a magic cauldron for those of us not so initiated. The modular synthesis began as an American bicoastal phenomenon with Don Buchla on the West Coast and Robert Moog on the East Coast in the 1960s, who were researching and developing products for musicians looking to explore new electronic sounds. Both had very different approaches. Buchla was more on the experimental side and interested in machine and generative music, while Moog was more interested in making playable devices for performers more on the mainstream side.

The experts say Tony Rolando’s creations lay between the two coast systems. One of Make Noise’s most acclaimed synths is the Morphagene, an experimental sampler that combines virtual tapes and classical cutting techniques with state-of-the-art granular algorithms to process sound—allowing the audio material to be recorded, sliced and rearranged in the twinkling of an eye.

On the other hand, Rolando sees modular synthesisers as a chemistry set operated by a man-machine interface in a continuous flow between the synthesiser and the artist/musician. He also sees Make Noise instruments as a collaboration with musicians to create once-in-a-lifetime performances that push boundaries and play the notes between the notes to discover the unfound sounds for which modular synthesis is so good at.

That’s one of the reasons he also created Make Noise Records, the record label he runs parallel to the manufacturer company. A project that started in 2012 with his friend Surachai, when they sent synthesisers to 5 artists (Richard Devine, Alessandro Cortini, Robert AA Lowe, Keith Fullerton Whitman and Surachai himself) and asked them to produce the Shared System Series of records.

You have described what you do at Make Noise as merging science and music. You are self-taught in electronics and circuit design, but do you have some scientific background? Where does the interest in seeing what you do as a scientific process comes from?

I was describing Modular Synthesis and not Make Noise specifically. Modular Synthesis is absolutely a merging of science and music. A modular synthesizer is like a musical chemistry set. You set up experiments and observe the results. It has more in common with performing a scientific experiment than performing a piece of music, and yet you are, in fact, creating music.

My scientific background is that I enjoy and appreciate science, which is an important thing if you are going to attempt to teach yourself how electrical signals are created, controlled and harnessed for a musical purpose.

You’ve also described how using a modular synthesiser is a collaboration of human and machine and that the device is highly capable of being guided but must even be allowed some freedom. Could you expand on this?

Sometimes it seems people want to control everything as if they know best, but I believe collaboration is a good friend of the arts, be it with human or machine, and collaboration is essential. To deny the machine a role in our creativity is to turn a blind eye to an entire plane of possibilities. Not all of them are good possibilities, but then not all of your human ideas are good either.

For your creations, you combine synth-building techniques and concepts of both the West and East Coast while at the same time incorporating new elements. What it’s the intellectual process during the initial stages of building one of your modules or synths?

Mostly I look at historical instruments, musical processes and music pieces to extract ideas from them that could potentially be applied to modular synthesis. I prototype an idea and get it in front of beta testers as quickly as possible. Time spent applauding your own creation is wasted time. If other people cannot feel inspiration from it, there is no reason to offer it. At that point, an idea is either retired or proceeds on to production-level prototyping and so on.

What has been one of your most challenging pieces of work and why?

The Morphagene and the Phonogene were both very tough because there were no pre-existing modules to look at for guidance. We had to look to mostly tape music, computer music and software for inspiration. We had to use books like “Microsound” by Curtis Roads to understand granular synthesis, and then we had to figure out how to make these musical techniques work well in an analog modular synthesis environment.

The Morphagene is one of your most praised creations. What is it that makes these modules so unique? Also, I’m a molecular biologist and intrigued; what are these “genes” in modular synthesis?

I cannot tell you what makes them so unique exactly because I believe that is different for each person who encounters them. Everybody experiences the Morphagene differently, for example.

The thing I always try to have in a module design is a sense of history. It helps me to understand where the device fits into the overall scheme of music and artistic process. It serves as a starting point. A very real starting point. Without history, we have nothing, really. Perhaps this helps people to appreciate them.

Going back to this idea of the human-machine collaboration, seeing the exponential growth of artificial intelligence technologies and interest in body enhancement and interfaces, what do you think about a mind-controlled synth, which would connect the brain neurons and synth voltages?

I don’t think much of it at all. Seems like a waste of time and effort to me… if you could create the exact music you hear in your head, or even if you could control a synthesizer exactly how you imagined in your head, it would likely be disappointing because there are very few people brilliant enough to have anything so well figured in their heads. We think we do, but we do not. Art thrives on collaboration and accident.

It looks Maise Noise Record label saw light as a way to showcase your products under the hands of talented experimental musicians. How has this initial idea evolved over the years?

When the label was started, we did not offer the Shared System or ANY systems. The label began with a single idea shared by myself and Surachai one night at a club called Zebulon in Brooklyn… send ONE synthesizer to 5 artists. Make records of what each of them do with the synthesizer… hope all the records sound REALLY different. The Shared System was created expressly for the record series. I consider it my contribution to the record series.

The label was expanded because people kept approaching us to take out ads in magazines, and I figured we could spend the same money making records as we would taking out ads. So why not give a little support to artists we appreciate AND promote what we ALL are doing, Make Noise and these artists? Make some records, and promote them. The label operates at a loss, but who cares.

Where do you see taking Make Noise into?

The future and it will not be like the past…

What is your chief enemy of creativity?

The internet mostly.

You couldn’t live without…

My partner in life, Kelly.