Interview by Marielle Saums

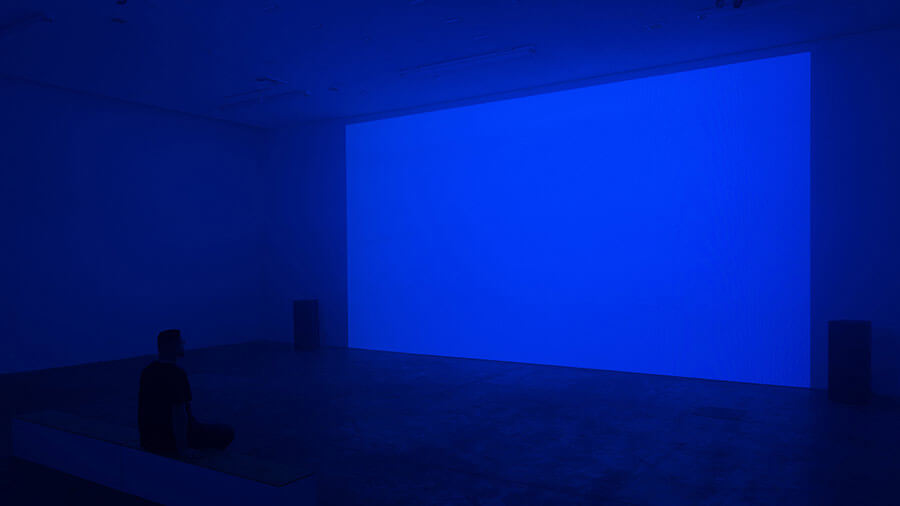

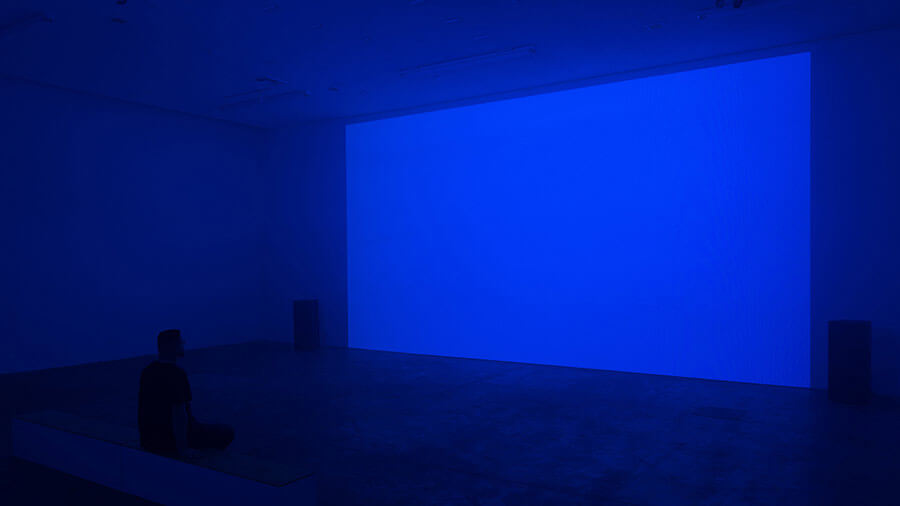

Listening to a Yann Novak composition is akin to sitting in Pacific Northwest rainfall. Whispers of field recordings and modular synthesizers gently percolate the atmosphere, and the listener can either tune out these sonic alterations or allow these sounds to soak us to the bone. His live performances and installations gently usher audiences into emptied spaces, occasionally saturated with fields of colour, giving us room to breathe in a world that feels increasingly claustrophobic.

His creative journey and approach to composition can be understood through the rhizomatic assemblage philosophy developed by the postmodern French philosophers Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari. In contrast to a tree’s hierarchical and binary structure, the rhizome embodies the multiplicity of ideas, flat growth and spontaneous propagation. Novak is comfortable at any level of the trophic scale of sound: from field collector and composer to installation artist and curator. Originally intent on being a visual artist, he circumvented traditional fine art hierarchies (such as studying music at a formal institution) to master new mediums and collaborate with artists across disciplines.

Sonic distortion of recordings is the foundation of Novak’s work and embodies the decalcomania of rhizomatic thought. Like smashing dollops of paint between two sheets of paper and marvelling at the unexpected patterns that emerge from the mess, he masterfully tempers the chaos generated by distortion to transform raw noise into profoundly different sounds. In his work, the silence of snowfall becomes lush static, cracking glass creeps, and the emptiness of desert landscapes builds into an overwhelming hum.

Novak’s origins as a DJ inform his ability to arrange prerecorded forms into new compositions that are informed by spatial constructs. Straddling visual and sonic experiences in works like +Room-Room (2009), Novak tunes into architectural acoustics in order to direct the movement of performers or the audience throughout a soundscape. Even though his work is ambient in nature, he embeds cues for personal movement that translate well to his collaborations with dance choreographers, such as A right-angled object (2014) and The Intertia of Time (2018).

Rhizomatic assemblages embrace entanglement, but Novak has created distance in order to step back and gain comprehension of the broader structure his works inhabit. In contrast to DJing, which requires constantly adjusting music to the audience’s reaction, he has limited the presence of other people in the formation of his work and is becoming more selective of the projects he chooses to undertake. As evident on his latest album, The Future is a Forward Escape into the Past (Touch, 2018), this newfound structure has expanded Novak’s experimental palette while retaining his ability to summon listeners into the present moment.

Your work expands from sound art, sculpture, architectural interventions, new media, and installation. When and how did the fascination with them come about?

I came from a very musical and sound-oriented home––my mother was a musician, and my father was a record collector and radio DJ. They always encouraged me to explore my creativity, but as a child, I was much happier drawing and painting than learning the different instruments presented to me at one time or another. I think this was because I was very shy, and no one else had to experience the failure of a drawing… those around you are not so lucky with an instrument.

When I came of age, I was deeply immersed in the 90s rave scene and did a lot of DJing, but somehow always thought I would end up as a visual artist. As the 90s started winding down and I was sobering up a bit, I saw a Bill Viola show in my hometown. The standout piece for me was The Theater of Memory. It’s made up of sound, a projection, and an uprooted tree with lanterns hung on its branches. This was my first exposure to an installation, and now, as I look back, I realize that something really clicked for me then: the immersive experiences raves offered were similar to multi-sensory installation works like Viola’s.

I still made bad paintings for a number of years after that, but during that time, more and more experimental music was finding its way into the world. Then I read this article on Steve Roden in The Wire in 2003, and I think that was my first exposure to an artist really working in both worlds. I was already playing around with making sounds, but I think that revelation somehow gave me permission to stop thinking about them as separate things and instead as different sides of the same thing.

Shortly after that, a coworker who was also a choreographer invited me to score her next big piece. I accepted and was immediately thrown into this interdisciplinary and collaborative world that kind of served as my art school. After working with dance, I could never really see divisions between all these different mediums, so for each new project that came my way, I would approach with whatever medium made sense for it rather than limiting myself to one medium.

For your most recent artistic investigation, you say the central concept articulates around a Terence McKenna phrase, ‘Exploring the felt presence of direct experience’. Could you expand on that and how it relates to your artistic aims?

This idea in relation to my work is still kind of forming––I find I can’t totally explain something until I have moved past it and can reflect on it. It’s easier for me to give a little context and explain how I got there. For about 10 years, I limited myself to only using field recordings because it created this really easily defensible concept, but it also painted me into a corner.

As I got frustrated with these self-imposed rules, I started to notice this kind of meditative quality that was always present in my work. I think it was a response to being actively present for my field recording sessions, having to sit silently and still. This presence carried over into how the audience interacted with the work. I became fascinated with how this attribute that was inherent in the process of making the work was also present in how audiences engaged with and experienced it.

Once I had this realisation, I became far more interested in this exchange between the audience and the work than in limiting my process in order to make it defensible. That left me with far more freedom but no real language to talk about what I was trying to achieve with my new work. I had been a fan of McKenna’s writing since the early 90s but had not revisited it in years.

Then I happened to come across a lecture he gave in which he talked about “the felt presence of direct experience.” Of course, he was using it in relation to psychedelic drugs, but that phrasing so perfectly described what was happening to audiences experiencing my work that I adopted it as a stopgap.

It’s still really an exploration––how is that quality carried over? Why does it evoke focus and not just spacing out? I think these unanswerable questions are what make it so exciting to explore.

In some of your collaborative projects, you try to blur the boundaries between figure and landscape using field and audio recordings, video, and installations. What are the biggest challenges you face for them?

When mixing certain media––say, sound and video––it can be easy to set up a situation where suddenly the audience feels like they are in a movie theater or watching TV. Because of this, I am always trying to find ways to subvert expectations, from simple things like projecting onto a wall one might not expect or letting the audience come and go during a concert. I think of what I do more as creating space for listeners, audiences, bodies, etc.

So the biggest challenge is usually what in architecture is called “programming,” or the intended use of space. I have done a lot of work in hallways and stairwells. Both are traditionally transitory spaces––one is not meant to dwell in them but rather move through them. My challenge then becomes how I suggest they pause and take in the space rather than move through it.

This can be a challenge, but it’s also my favourite part of making work. I don’t think of a piece as finished until it has been installed. I think of the installation process as an extension of my studio practice. One of the things I miss about my old tactic of limiting myself to field recordings was there were always variables I could not plan for––I was always butting up against the materials. But architectural situations have become the new obstacle I happily run into.

Could you tell us a bit more about the intellectual process behind your latest album, The Future is a Forward Escape into the Past, out at the end of the month on Touch?

For a long time, my albums have taken the form of documentation of installations or performances. They were never their own thing. They were more of an artifact of something missed. For this record, I really wanted to break out of that cycle and make an album where this specific format was the intended end result. In order to do this, I started to look back at some of my early work, back when it regularly culminated in an album.

As I did this, I couldn’t help but draw a parallel to the current political climate in the US and elsewhere, this impulse to “make things great again.” The ‘again’ is what I really became fascinated with: it goes beyond nostalgia, I think, to a kind of rewriting of history through selective memory. So I set out to do the same with my own work, but instead of erasing the “bad”, I wanted to learn from it.

One of the clearest examples of this was the reintroduction of distortion. I used to use it a lot, but I stopped because it started to feel like an easy go-to for creating tension or climax. The last time I used distortion on an album this heavily was on Meadowsweet, which I made just months after my mother passed away. For that album, distortion became the perfect tool for sonically translating pain and creating emotional crescendos.

For the new album, instead of trying to forget the negative relationship selectively or avoid crescendos, I just tried to forget how I used it and find a new approach to it. It’s still emotive, and I probably get closer to a crescendo than I have in a long time, but now it’s more of a flourish rather than a driving force. My intent was to avoid the impulse to be nostalgic and instead try to learn from my past.

What directions would you like to take your work into?

Up to this point, I feel like my practice has been fairly reactive. I am always bouncing from one opportunity to the next. I never say no, and I don’t want to start, but after a while, it has started to feel like I am not in the driver’s seat. Each project has a relation to the last, but I never have the time to fully reflect or make a conscious decision to go in one direction or another. This also leaves very little room for play.

My new album felt like the first time I have been able to be proactive. I had a break in 2017 after my last solo show and made a conscious decision to dedicate that time to a new album and nothing else. I don’t really know what new direction I want to take my work, but my hope is that I can have a more active role and not just move from one project directly to the next.

What is your chief enemy of creativity?

Capitalism. I love to keep myself away from the studio and let ideas build up and up until they cannot be contained––I have done some of my best work that way. But as I get older and as the responsibilities pile up, the task of making a living has started to really hamper my creativity.

Keeping myself out of the studio as a creative exercise is much different than being kept out of the studio in order to make a living. The latter does not offer room for ideas to build and flourish. Instead, it makes room for anxiety to build and flourish. It’s maybe not the most exciting answer, but I think it’s the most honest answer.

You couldn’t live without…

My partner, Robert Crouch.