Interview by Silvia Iacovcich

Robert Gerard Pietrusko is a designer, composer and educator who investigates the strain of everlasting data in time and space. Using multiple resources and jumping unstoppably from one field to the next one, the composer effortlessly switches his attention from the permanence of sound (Six Microphones) to the value of citizenship in society (In Plain Sight) – while inspecting the obscure angles of space travel.

Pietrusko anatomises the tangible realm, combining an original and unconventional approach that bridges the academic and the unceremonious – and the audience is quickly absorbed into his generative blend of practices. Through ‘audiovisual composition, immersive interiors, and narratives of the future’, the artist challenges those ‘situated knowledges’ – Haraway’s myth of scientific objectivity – as a means to understand that all judgements come from positional perspectives.

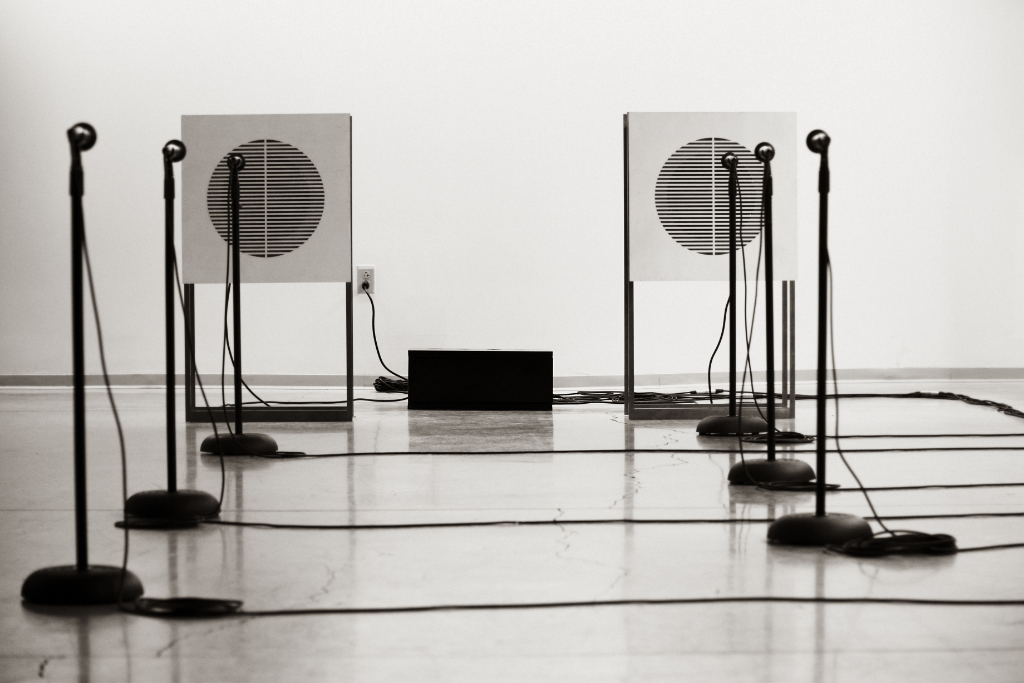

Six Microphones analyses the immanence of sound as a watchword. The installation, set in 2013 at the Storefront for Art and Architecture in New York City, consisted of mics, a surrounding space, and an audience to carve out a site-determined composition bound together by a finite interconnected system that led to a sound with its own agency.

Using sound as a system of internal homeostatic parameters, kept in a state of resonant feedback within an architectural space, the listening audience was confronted by a dynamic system that defined its complexity through its absence of complication, following a simple paradigm: six microphones pointed at six speakers.

The project resulted in a twenty-year analysis that explored the mutually constitutive relationships between sound, space, and audience, rendering a musical space and making its contingency evident in all its congruence.

The relationship between geometry and territory is reshaped from Pietrusko’s video excerpt from his latest album Elegya, released last summer on Room40, the experimental record label run by experimental master Lawrence English. UTM39N displays a fragmented vision of a natural scenery, with trees aligned into rectangular prisms gliding over the hypnotic synths of the track, resulting in an inaccessible frame lost in time.

The natural element follows Pietrusko’s second extract from the same album: in Room, eloquent close-ups of nostalgic images of a dissipated nature are brought together from 16 mm footage taken from the 20th-century Soviet archives, early video and computer graphics.

The shots remerge through the vision of filmmaker Courtney Stephens in a collage that explores our changing biosphere – resurrecting a historical time and world that belongs to the past, though it might have never occurred. The five piano motifs that inhabit the album create vigour and change, as Pietrusko explains, but never progress, approaching recurrence as the origin from which all variations are derived – an abstract highlight that retraces the perception of our present times.

As a visiting faculty member at Strelka and Associate Professor of Landscape Architecture at Harvard University, Pietrusko readdresses the same patterns in a different praxis, experimenting with how the science of ecology can expand into the design domain, analysing solutions that allow our generation to operate in a way that is good for the biosphere and for ourselves.

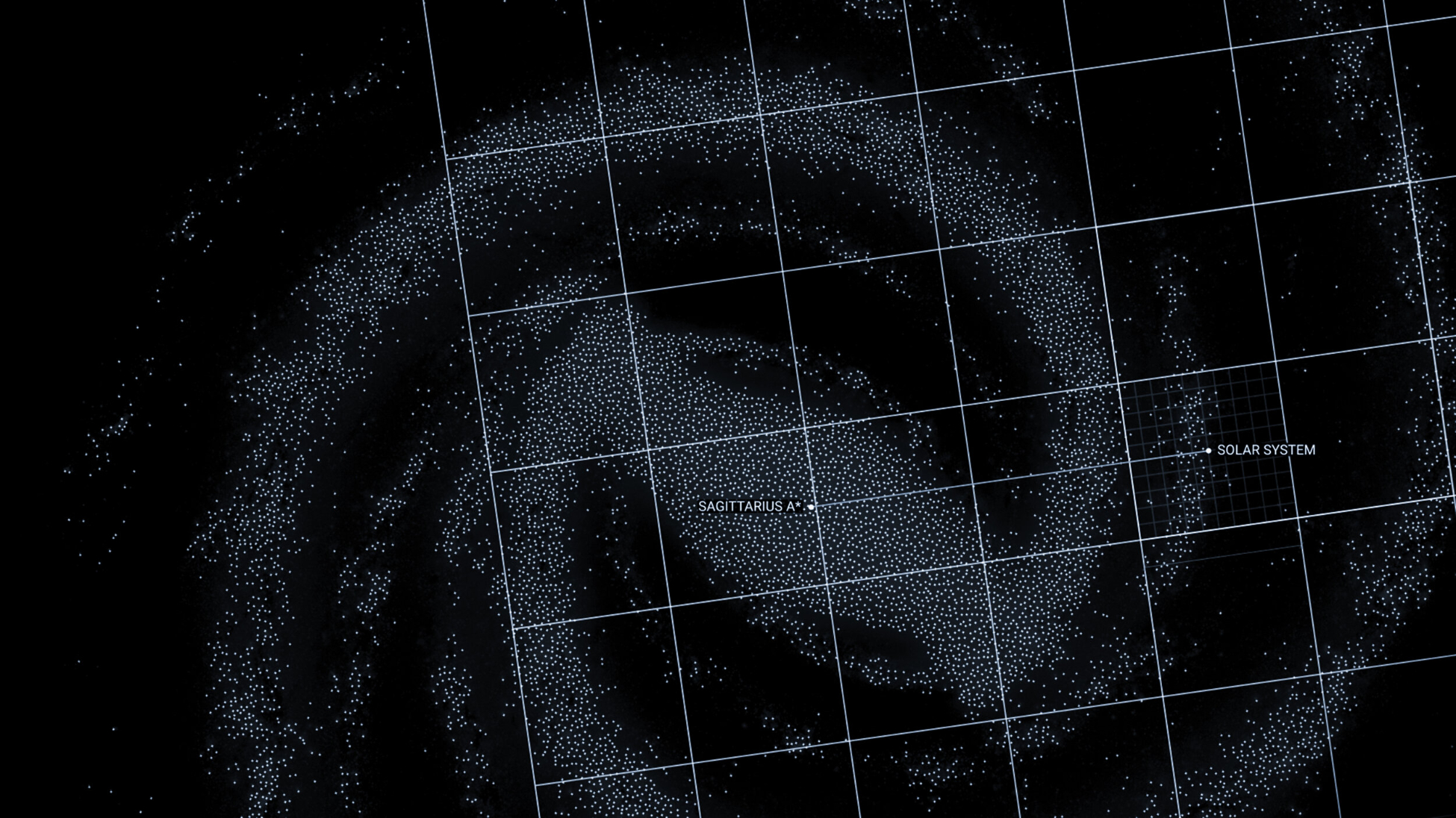

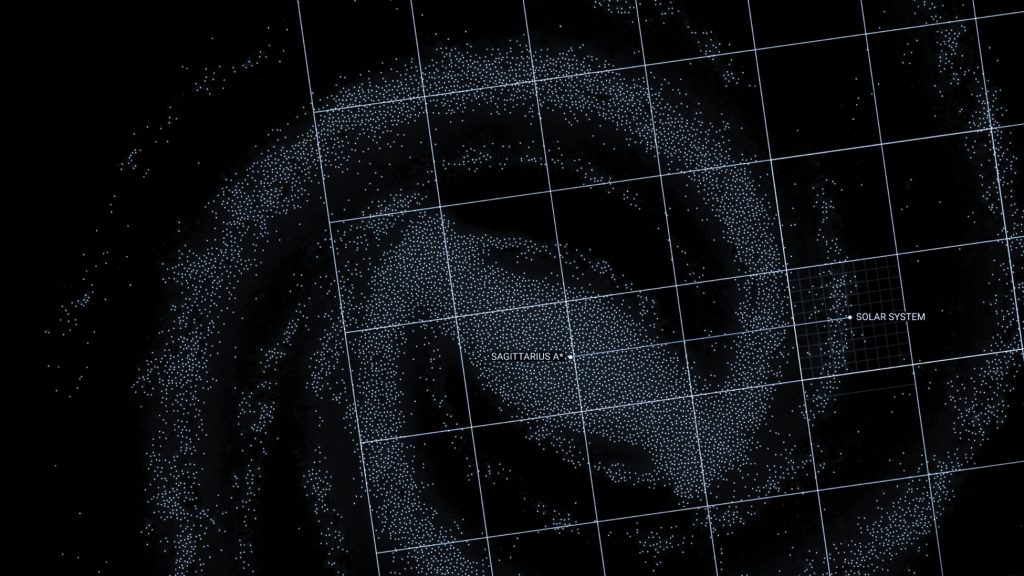

When he’s not diving into the sinewave’s role in music or speculating on terraforming upshots, the designer implements ways of deploying graphics to clarify in Black Holes – The Edge of All We Know the vast distances involved in the Project Event Horizon, for more unrestrainable sources of inspiration.

Right: Elegiya album cover (2021). Both photo credits: ROOM40

You have a Bachelor’s degree in Music Synthesis, a Master of Science in Electrical Engineering, and a Master of Architecture from Harvard; how has this journey developed and shaped your practice from the early stage of your career to Warning Office?

When I was a teenager, I was exposed to three influential projects in rapid succession: (1) The collaboration between Xenakis, Varese, and Le Corbusier for the 1958 Philips Pavilion; (2) Buckminster Fuller’s “Geoscope”; and (3) “The Fundamental Acts” by Superstudio. Before then, music composition was my only ambition, but I imagined an expanded media practice combining audio-visual composition, immersive interiors, and narratives of the future through these projects. So I spent the next 15 years stitching together what I thought were the necessary basic skills. Though I don’t directly reference these projects often, I recognise that all my work is related to them.

Six Microphones is a site-determined composition of audio feedback. In an attempt to create a composition with its own agency, the artwork senses and responds to its environment. Recently, it has been released on LINE (Richard Chartier’s LA-based imprint). What was the intellectual process behind the project, the choice of the installation location (Storefront for Art and Architecture in New York City), and what drove you to want to work with feedback?

I was interested in the sinewave’s transcendental role in music, especially during the post-war fervour for electronic music. It was connected to theories of total musical control that seemed to promise a pure, absolute, and immaterial form of composition.

This iconic status always seemed inaccurate to me. It was contradicted by the messy reality of actually existing sinewave generators; as an engineer, I had built many of them. I wanted to make a piece that grounded this image, where the fundamental operation of the sinewave was embedded in its materiality, contingent on its interactions with the environment, and out of the composer’s control—no transcendence, pure immanence.

Circuits conventionally produce sinewaves through stabilised feedback, so I exploded the scale of this process to include the listening space itself. The piece amplifies the sound of the gallery until a resonance is established within the system. This is all stabilised with a control system.

I liked that there could be a “composition” that unfolded in time that had no intrinsically sonic version—this would instead be determined by the interactions among the system, the space, and the placement of bodies within it. Feedback, therefore, wasn’t the purpose of the piece; it was the outcome of the process.

When considering its implementation, I appreciated the legibility of six microphones pointed at two speakers. Simple in form but hopefully unexpectedly beautiful inexperience. Mounting it at Storefront was a lucky set of circumstances.

I was originally asked to propose a piece for the space in 2009. I thought Six Microphones would work nicely with Holl + Acconci’s geometries. It didn’t end up happening at the time, but years later, my friends at ESP-TV were doing programming for Storefront’s 30th anniversary. They remembered my proposal and invited me back. (It has since also been mounted at the Carpenter Center for Visual Arts, Le Corbusier’s only building in North America.)

In Plain Sight is an audiovisual installation designed for the 2018 Venice Architecture Biennale, where you explored Global citizenship through a 20-minute animated data narrative. In times when it seems that data is a source of misrepresentation or fake reality, what does developing this project make you think about? How can a more fair use of data and data technology be promoted?

When discussing data, we often concern ourselves with representation, objectivity, and accuracy. (Unsurprisingly, we are repeating many of the conversations we had about photography throughout the 20th Century.) The pieces that I make using data are often based on an underlying belief that data are not representational; they are rhetorical. I’ve found Donna Haraway’s concept of “situated knowledges,” inspiring and useful in this regard.

For her, objectivity isn’t an absolute trait. Instead, there are numerous objectivities—each one a chain of material conditions that frame the world in a specific way. This means that many datasets are equally real and equally “objective,” even if they contradict each other. They each come from a situated and bounded position. It is, therefore, up to us to use data to make arguments on behalf of a worldview rather than being beholden to its seeming objectivity. Though difficult, this should be part of the cultural and political work of collectively aligning the world to our values.

You are also a visiting faculty member at Strelka Institute, which launched a new research/academic programme on Terraforming. What has been your involvement in the new programme?

Like many of the faculty, I normally spend a week in Moscow with the research cohort. We work closely on a fast-paced design charette that, despite the short duration, is usually conceptually rich and rewarding. The new program has coincided almost entirely with the COVID pandemic, resulting in a reorganization of this process.

Bandhas also generated some new topics of contemporary relevance. This year my workshop focused on “conspiratorial styles of reasoning” and their overlap with design methodologies. I presented four events that are often described as “natural disasters” and asked the cohort to invent conspiracy theories that would be necessary for each event to have been intentionally designed.

There is optimism in the exercise because the resultant conspiracies often highlighted the network of institutions, actors, and processes that could be mobilised in new ways to address global environmental issues. Ultimately, this was the purpose of the exercise, to imagine the network as having the potential to operate in a way that is affirmative for the biosphere.

Speculative Design and critical thinking have been fairly used as a way of criticism and advancing current design methods, but in recent years, a too-a growing number of Speculative Design projects seem to be missing their critical and sociocultural punch [like the Audio Tooth Implant by Auger-Loizeau (2001)]. As a designer, what is your opinion on the current situation?

First, I should say that I found the work of Dunne & Raby very inspiring when I was a design student; that people are still using the “speculative” modifier to talk about design is an indication of the importance of D&R’s early experiments.

More generally, though, I think that all design is speculative, especially if we consider its core activity: making depictions intended to persuade others to organise matter, energy, and labour in a particular way—even if the designer never intends for it to be realised. For conventional design projects, these depictions often attempt to make contemporary ways of being more efficient, comfortable, invisible, or any number of other virtues that support the current capitalist system of values.

It seems that most speculative design projects are reacting against this. I think this is a good thing, but I also agree that the nature of the reaction has lost its “sociocultural punch,” as you say. It has mainly been reduced to a methodological genre: take something from the present, extrapolate its logic into the future until some absurd outcome is obtained, and then make a half-hearted claim that the project exposes latent aspects of our present condition. It’s often a bit like satire.

But, unfortunately, the issues of our current condition are not subtle or latent, is no need for a witty exposé. In my opinion, a better agenda for speculation would be an affirmative and prefigurative form of imaginal politics that has the guts to make propositions for radically different organizations of our world. This is incredibly difficult, but I think it is what design, at its most speculative, can offer at this moment.

In the documentary Black Holes – The Edge of All We Know, you worked on creating the data visualisations for the film, which is really intense and follows the passion and the wonder of a group of scientists in search of the perfect pic of a Black Hole. How was working with Peter Galison and the scientists’ team?

Working with Peter was great. We had collaborated on a few previous projects, including his 2015 film “Containment” (co-directed with Robb Moss), and took a similar, highly iterative approach. My team and I were designing for an audience that has a broad spectrum of understanding regarding the topic— astrophysicists on the one hand and curious but novice viewers on the other (which I was myself before getting involved with the project). I liked thinking of our maps as an extension of my work in landscape architecture. The field has a long history of attempting to represent a sublime nature while not disciplining it.

But what is more, sublime than the nauseating scale of the universe? Communicating the distances involved in the Event Horizon project both quantitatively and emotionally was a good challenge. Of course, we also had to acknowledge that we live in a world where the film “Powers of Ten” exists and that we have learned from it while not wanting to reference it directly. It took some time to arrive at an approach for that.

In your latest album, Elegiya (ROOM40, 2021), the elegiac theme intersects with the conceptual structure of the work. You approach repetition as a starting point from where all variations derive – this abstraction is intrinsically and authentically existential; it feels as if each modulation could analyse a different life path, and becomes very visual. Is it intended?

The year 1991 and the collapse of the Soviet Union were 30 years ago. As a young kid, I was engrossed as it unfolded. My whole understanding of the world’s organization was predicated on the clear and seemingly eternal division between capitalist and communist countries held in stable tension by the threat of nuclear Armageddon. Then, suddenly, it was over. This was quite shocking to me. (I might compare it to learning next week that there are no more countries and that the climate crisis is over.)

In 2019, I re-read Alexei Yurchak’s book, Everything Was Forever Until It Was No More. In it, he explains the duality of the late Soviet experience: It seemed that Soviet society would go on forever, and yet, when it collapsed suddenly between 1989 and 1991, its end was also somehow expected. Yurchak’s argument is, of course, much richer than this. But in short, the duality, or ambivalence in it, felt like an appropriate description of late Capitalism as well. Also, how each era enacts a repetitive compulsion for monolithic instability and global crises.

There has been a lot of beautiful artwork and music created in response to climate change or the excesses of contemporary capitalism. I was trying to find musical forms to also respond to these things in the larger repetitive sense mentioned above.

I arrived at five piano motifs that were extrapolated across the album. In each piece, there is vigorous movement and change but never any progress. I wanted it to feel like the whole album might fall apart at any moment, but instead, it continues, repeats, and varies itself. I was reflecting on how the Elegy, as a musical and poetic form, had previously served this function, and I was hoping that these unstable-but-repetitive forms might be a new Elegy for our contemporary moment.

What is the technological advancement in your field you are most interested/intrigued to see its development and how it will impact societies or your main research area of interest at the moment?

Lately, I have appreciated how the science (not the metaphor) of Ecology is being deployed as a projective design tool rather than merely an analytical one. Relatedly, I believe that possibly one good thing to come from the pandemic might be a new intuition for nonlinear network dynamics in the public at large. From having to internalise the worldview of epidemiological models to understanding how we’re all connected through supply chains, I am hopeful that the mindset of neoliberal individuality has been discredited for most people.

What is your chief enemy of creativity?

Multi-tasking.

You couldn’t live without…

Autumn, alone time, other people’s music.