Text by Miguel Isaza

Electronic music is not a genre, nor is really a style, nor is it limited to a series of technical methods. Beyond these more categorical discussions, it’s the introduction of the electrical, electronic, analogue and digital dimensions to the more classic musical creation processes, thus preserving the previous existing ideas about music, sound, listening, noise, silence and other associated elements.

Electronic music can also be a departure from the canons of the pre-electronic era insofar as machines in a relationship with organic entities creating new cyborg paradigms, opening the way to transgressive, futuristic and subversive figures in the musical scene, capable of transcending sonic anthropocentrism and musical hegemony.

From tape to voltage

In the history of the French electronic and experimental music movement, alongside musicians such as Pierre Schaeffer and Pierre Henry, another pioneering figure reached aesthetic, conceptual and spiritual boundaries never before witnessed by their male colleagues.

We are talking about Éliane Radigue, an artist still active whose work reflects on one of the deepest searches that could be found in the music of our days. Every single day in the life of Radigue, from her birth in a family of merchants in Paris until her most recent concert at the presences electronics 2022 festival at the legendary INA-GRM Acusmonium, has manifested an exceptional sonic revelation of the highest -although not inaccessible- electronic mystique.

Radigue’s work began with experiments on magnetic tape characteristic of the concrete music school, where it was usual to use recordings of all kinds to break them down, repeat them and generate new compositions from there. She was an intern at the Studio d’Essai at the RTF in 1958, where she worked, hand in hand, with Pierre Schaeffer and Pierre Henry at the beginning of the so-called concrete music genre. However, she later departed as she wasn’t finding the right spot for her creativity as a woman.

From there, she became interested in exploring “feedback”, and between 1969 and 1974, she carried out several experiments with soundscapes based on loops of several tapes played simultaneously. Later, she travelled to New York, where she recognized herself in movements such as the minimalist school, devoting her efforts to learning classical composition on instruments such as the harp and piano. This knowledge would come together in what would be one of her most prolific moments: her encounter with synthesizers. A moment of love sparked by stumbling across a Buchla synthesizer (sitting in a New York studio that she created in collaboration with another electronic music mastermind, Laurie Spiegel) that completely captivated her and her work.

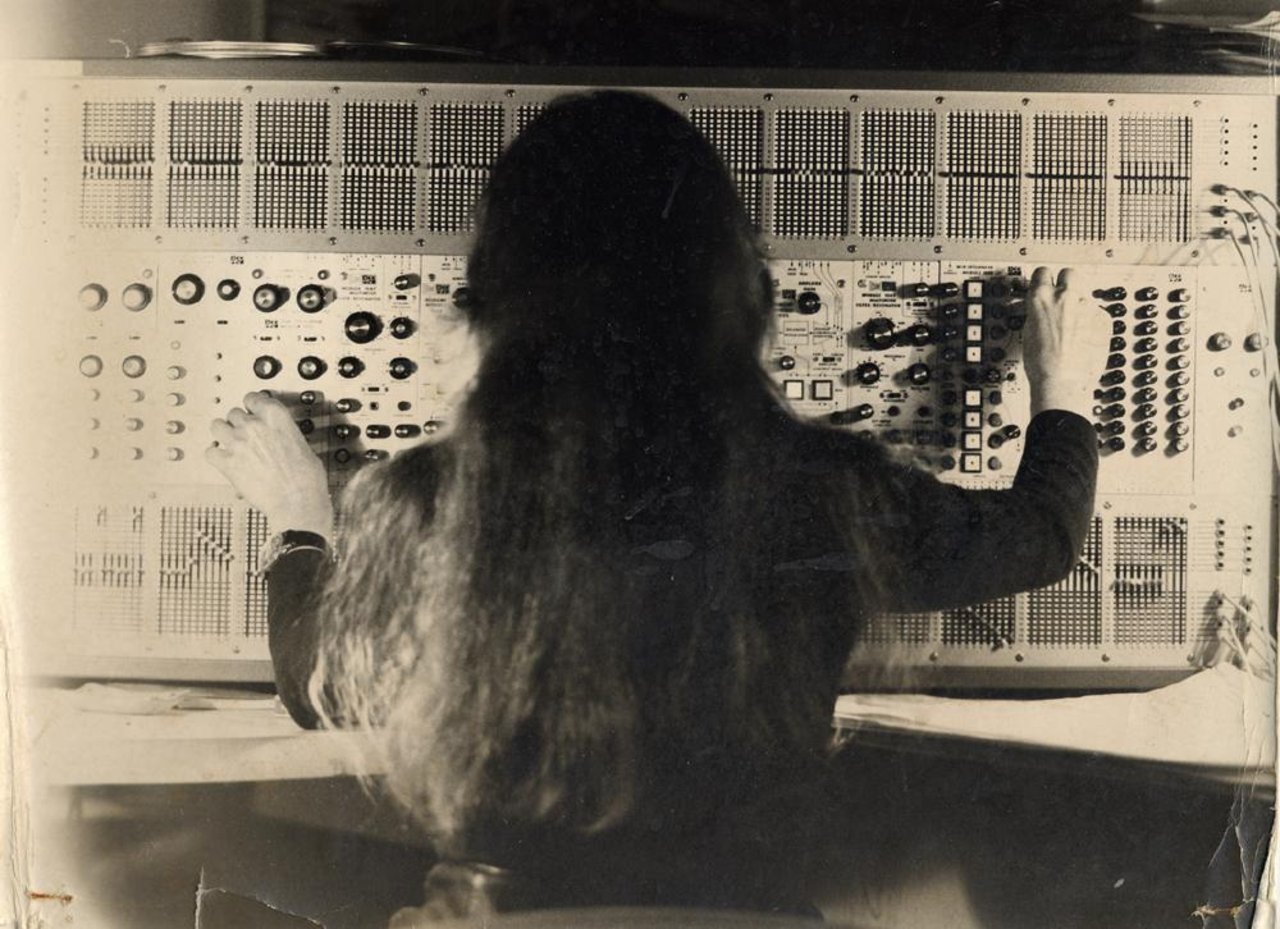

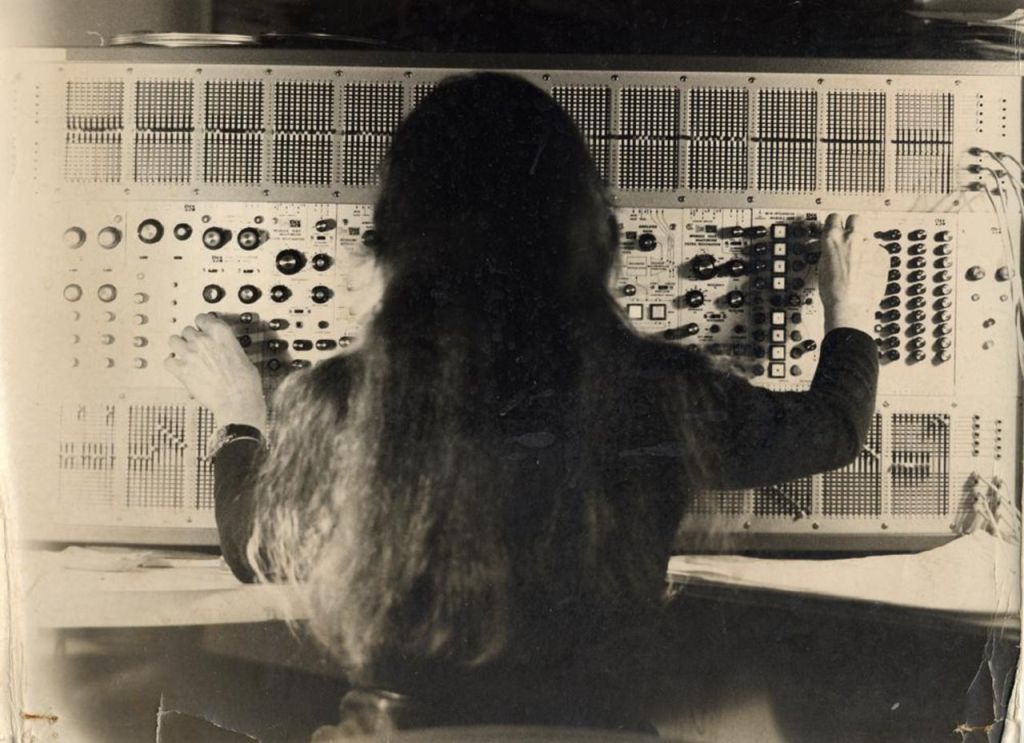

But the Buchla wasn’t meant to be the instrument where she would find her uttermost analogue passion. It was an ARP 2500, which she has always used without a keyboard, with crude oscillators, seeking direct expression from the potentiometers of what she called “the Stradivarius of synthesizers”, an analogue instrument that she explored in a totally unique and delicate way.

The ARP 2500, along with her tape machine, was the chosen one; and the one that would constitute her work for the next 25 years. Beginning with the piece Adnos I (1974) up to L’Ile Re- ringing (2000), and keeping her influence of previous processes with tape and feedback, she would delve into a search for layered sonic continuity, subtle variation, infinitesimal change, stopping before microsound and the perpetual ode to the slow, lacking a strict narrative and filled with a deep investigation into resonance.

Beyond Time

Radigue rejects the idea of the drone, as she does not conceive of her music as static but rather quite the opposite: consistently variable and in constant development. I love when changes happen without us noticing, she tells Kate Molleson in an interview, an idea she expands on in a short essay titled Le temps n’a pas d’importance (Time is of no importance):

Time doesn’t matter. All that counts is the duration needed for smooth development. My music evolves organically. It is like a plant. We never see a plant move, but it is continually growing. Like the plants, immobile but always growing, it is my never-stable music. It is always changing. But the changes are so slight that they are almost unnoticeable, only becoming apparent after the fact. This music, as I conceive it, cannot contain any cuts, so the structure is quite simple, based on fades – fade in, fade out and crossfade.

According to the composer, when working with Buchla, it was sometimes difficult not to radically alter what she was doing by disconnecting something she shouldn’t or making a wrong move. But with the ARP 2500, there was a direct feeling and an appreciation of the noisy qualities of its oscillators.

Her explorations continued to expand her listening philosophy, and her idea of sound embodiment embodied in pieces such as ψ 847 (1973), where matters that would be transversal in her music can already be glimpsed, such as the play of resonances, the call to contemplate the waves and the lack of obvious cuts or structures.

Sonic Buddhism

To say that the ARP 2500 was the central component of her work during this period is not entirely accurate, as the other element that would complete Radigue’s equation would be missing: Buddhism, specifically Tantric or Vajrayana Buddhism. In it, in addition to meditation, a series of tantric, body-mind processes are integrated, aimed at transmuting vital energy around the liberation of suffering; techniques in which sonority is often given paramount importance, as evidenced in the recitation of mantras and the deepening of listening as a way of liberation, elements that could not be more compatible with Radigue’s meditative sonic dimension.

Radigue encountered Buddhism in 1975 from the hand of a group of listeners. They were students of Robert Ashley at Mills College, where Radigue had attended to give a recital, and after which some people from the audience approached her to talk about the closeness they had found between Buddhism and her work, already meditative and slow by that time.

Those who approached her asked her a question that would completely transform her path: Did you know that you are not the one who makes the music? The three were disciples of Lama Kunga Rimpoche, and along with their concern, they left her an address to the centre of Buddhist practices of the Karma Kagyu lineage in Paris, where the composer tells of having gone just after she returned to France to “never look back again.”

Such was the impact she felt before the Buddhist way of life that she left her musical activity for three years to dedicate herself fully to the practice and study of Buddhism under the guidance of her guru, his eminence Tsuglak Mawe Wangchuk, 10th reincarnation of the great Pawo Rinpoche, and a recognized teacher of the mentioned lineage.

Radigue would spend this entire time following the instructions of her teachers, which ended in the same place where it all began: in music; since it was her spiritual guide who encouraged her to return to her work, which, although she continued with the Adnos trilogy and versions II and III, later she began to integrate a more direct influence of her Buddhist knowledge.

During this period, dating back to the end of the 70s, Radigue began a conceptual and sonic exploration where her spiritual quests integrated with her creative methods, the minimalist aesthetic, and the attention to detail characteristic of her work. She dedicated several works to the saint Milarepa of Tibet, an exalted poet, singer and enlightened man who left his story in songs often part of the prayers and spiritual practices of practitioners of this form of Buddhism. This is reflected in pieces such as 5 Songs of Milarepa and Jetsun Mila, where she also included the voices of the composer Robert Ashley and his teacher Lama Kunga Rimpoche.

After that period, one of her most famous works would come: Trilogie de la Mort, depending on the spiritual temperature of the listener. Radigue reminds us: It was the two extremes: one to throw it all away, the other to be captivated.

The trilogy of death comprises the pieces Kyema, Kailasha and Koumé. The artist completed the first one, Kyema, in 1988, taking inspiration from the six intermediate states or Bardos described in the Bardo Thodol, translated as Liberation by hearing during the intermediate state, also colloquially known as the Tibetan Book of the Dead. In it, coordinates of intermediate consciousness states are established. According to tradition, both people and other life forms navigate and constitute the perpetual cycle of existence, which is presented as a dynamic form in the void, the perfect analogy for music, in the words of Radigue: a silence that is the basis of sound – when it begins to vibrate.

The second piece, Kailasha, is structured as an imaginary pilgrimage to Mount Kailāsh, considered one of the sacred mountains of humanity, located in the high Himalayas in Tibet. Mount Kailāsh, veneered by Buddhists and Hindus, is a place of miracles, chronicles and spiritual events, to which Radigue attended conceptually to build the piece.

Radigue completed it in 1991 as an inner sonic journey that, in turn, is a tribute to her son Yves, who died around that time at the age of 34 in a car accident. This tragic event, added to the death of her teacher Kunga Rimpoche (which took her to Nepal for her cremation), gave way to the closing piece of the trilogy, Koumé. In 1993 Radigue concluded the piece, a composition that delves into the transcendence of death and her understanding of it as part of the cycle of life.

Liberation by Listening

Throughout the 21st century, Radigue’s work has maintained its leisurely aesthetic and almost imperceptible evolution. However, it has taken on a new twist by focusing on acoustic and electroacoustic instruments such as the electric bass, computers with Max/MSP, and, in more recent years, the harp and wind instruments. Often the compositions come from collaborative works in which she composes “for the performer and not for the instrument”, as reflected in Naldjoriak pieces with artists such as Charles Curtis, Carol Robinson and Bruno Martinez. Also, the series of Occam harp pieces (with the first one created for the harpist Rhodri Davies), which she has continued with numerous expansions.

Another of her recent collaborations was an installation with her colleague and student, Laetitia Sonami, also a devotee of Buddhism and sister-in-law of Kunga Rimpoche. Although Sonami works from a different aesthetic than Radigue, both came together from their conception of sonority, an encounter that materialized in the work Le corps sonore created by Sonami, Radigue and sound engineer Bob Bielecki.

The in-situ installation was placed in the central part of The World Is Sound exhibition at the Rubin Museum in Manhattan. The piece played from the floor to the ceiling and changed as people climbed the stairs, altering the listener from an upward perspective, thus integrating the spiral architecture of the building and expanding the typical perspective of horizontal stereo into a vertical listener. It breaks through the impermanence of the waves bouncing in the acoustic space.

Discussing her philosophy of listening in a short video portrait made by IMA Fiction in 2006, Radigue speaks of listening to her work as a matter of perspective and contemplation that can lead to deep introspection and awareness of the fabric of sound or trigger the power of imagination, allowing the listeners to create their own movie:

It’s like looking at the surface of a river. There is an iridescence around the reefs, but it is never completely the same. According to the way in which you look, you see the golden flashes from the sun or the depths of the water. In a swimming pool, you can see the reflection of ripples on the bottom or have a vision of the whole and let yourself be carried away, by what I call ‘dream gazing’, or fix on a detail and make your own landscape.

Commenting on the reactions she has found in her listeners, it is not even the music itself, but the sounds acting as a “mental mirror” and reflecting the mood in which the listener is at that moment. She adds that if you are ready to open yourself up to them, to listen truly and devote yourself to listening, they really have a fascinating, magnetic power: I am not even speaking about what I have done with these sounds; that’s another story, how I organized them. But above all, I did listen to them a lot with the greatest respect, trying to understand what they had to say

Even in collaborations, Radigue has maintained the immersion and depth of her time with the ARP 2500, generally seeking to lead listeners to “awaken the music within themselves”. “We should give ourselves over to the sounds, be open to the sounds, listen to what is resonating within ourselves”, she says in a conversation where she talks about sound and its ability to allow us to detach from the ego and expand the imagination.

This transforming, intimate and transcendent force makes Radigue a master of time and sonic matter, capable of going beyond conventionalisms to make way for her own liberating and profound philosophy of listening, capable of daring what so many people are afraid of, infinity.

“Just leave your body floating in the wave

So leaving the mind

The spirit floating in the sound

Check what happens.”

— Éliane Radigue