Text by CLOT Magazine

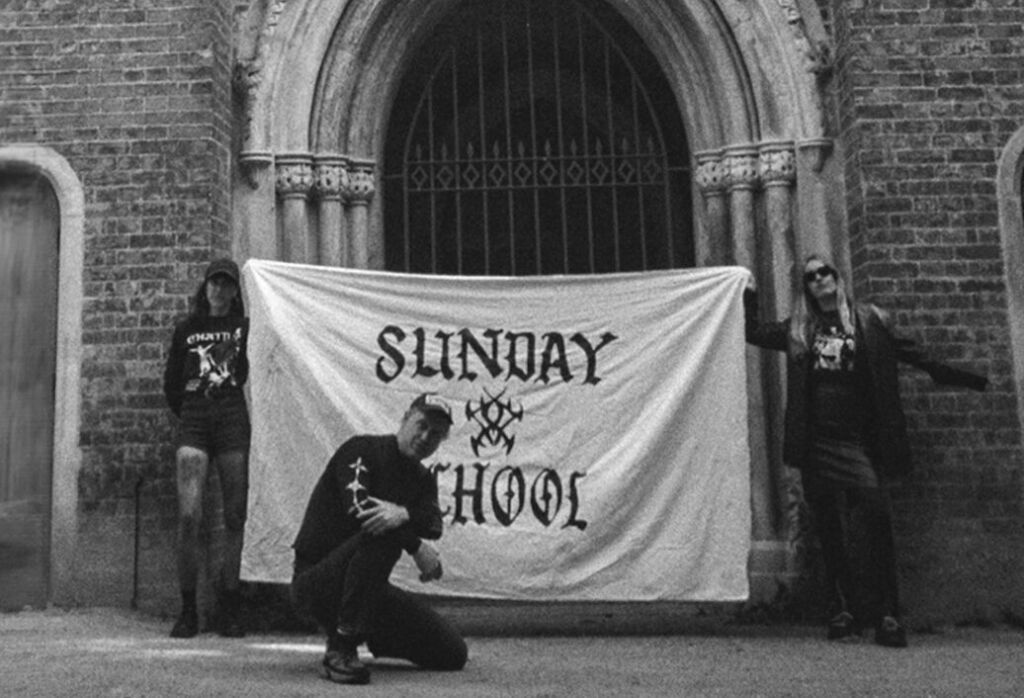

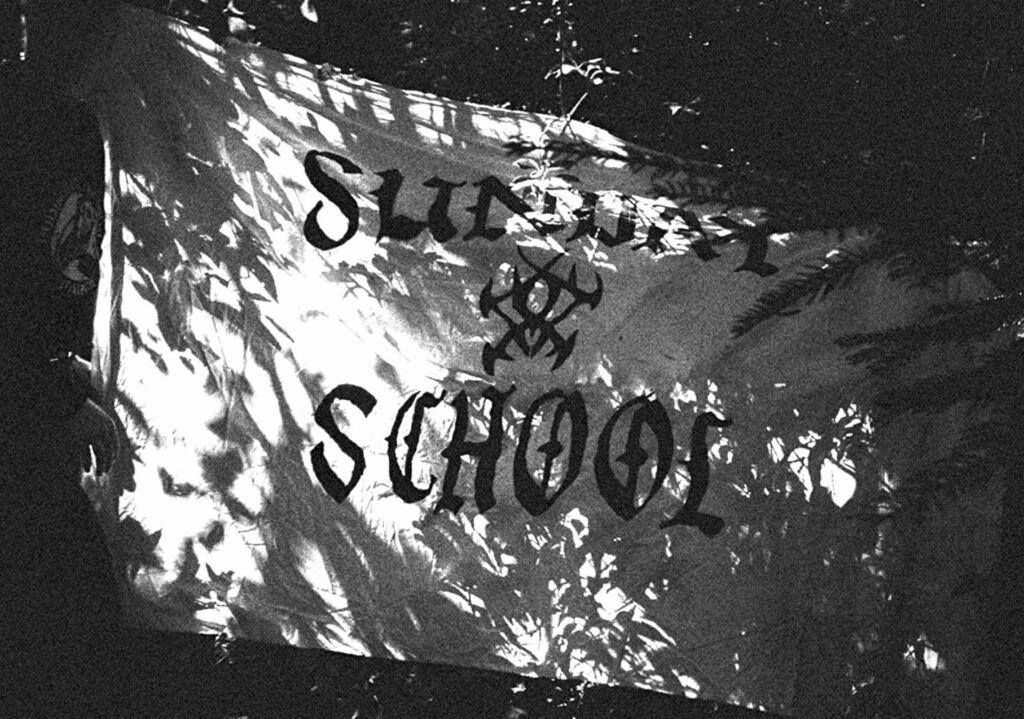

From the visceral heart of London’s punk, noise, experimental, and DIY scenes, a unique biannual event series has emerged with force this year. Just days away from its third iteration (and the second in London), Sunday School, conceived by Dom Stevenson (aka YAWS), is set to return this week’s Sunday, August 25th, at the iconic New River Studios in North London. The lineup packs a fierce array of bands and live acts featuring heavy hitters like Russell Haswell and Autumns, among many others.

Stevenson has been a pivotal figure in the abovementioned scenes for years, weaving through them under various artistic monikers and bands. His deep-rooted involvement and wide-ranging experiences have shaped a distinct curatorial approach and vision. Sunday School, which began a few years ago in Stevenson’s native Australia as weekly Sunday night events, has since evolved into an all-day event format with community at its core. As Stevenson emphasises, the goal is to create a welcoming environment where everyone feels at home while also providing a platform for fresh, diverse lineups and giving artists who might not always get the spotlight a chance to shine.

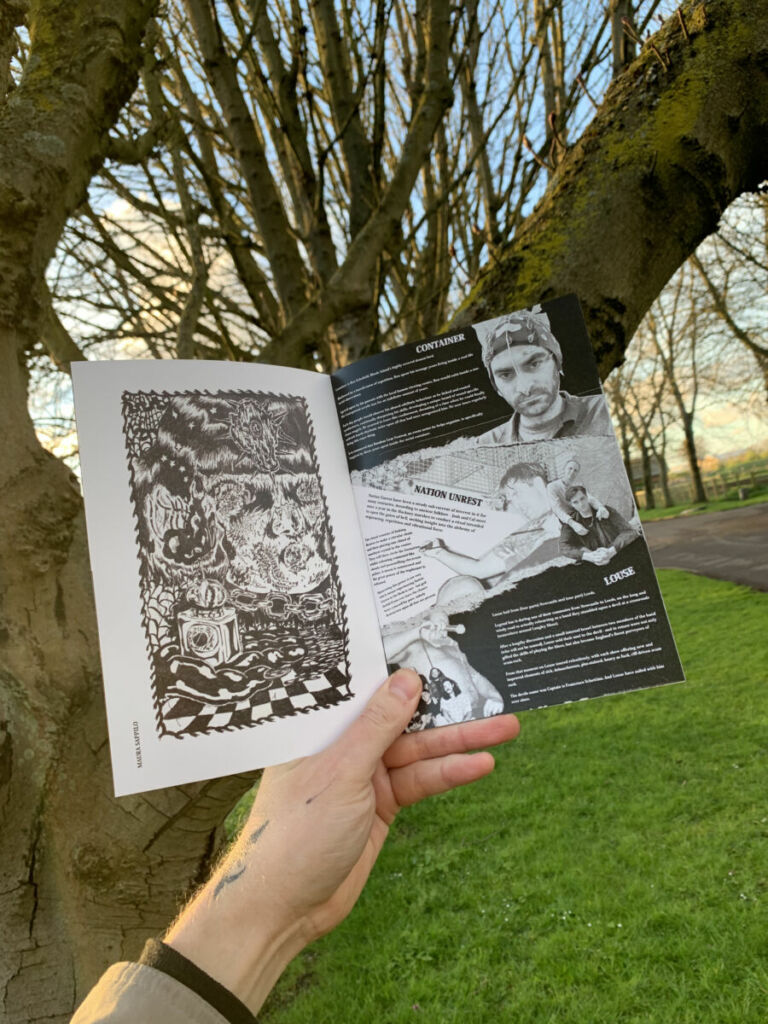

Another defining feature of Sunday School is the release of a dedicated zine for each event, showcasing handpicked artwork and text-based pieces. While Stevenson managed all the zine production for the previous Sunday School II, this time, he’s embracing the community-driven ethos of the event by collaborating with multidisciplinary analogue artist and close friend Minerva Amiss. Minerva will bring her unique ideas and style to complement Dom’s vision. Her earlier work delves into the constraints of human existence, particularly from a woman’s perspective, while recently, she’s been more involved in live events, serving as an artist liaison.

Joining the team for this edition too is Pauline Iedra, an active member of London’s DIY and punk scenes. Pauline is helping with every aspect of the event’s organisation—from ticketing and door management to promotion and the many eccentric, venue-specific tasks required to bring this event to life.

We spoke with Dom Stevenson and Minerva Amiss to delve into the interplay of art, alternative scenes, and subversive soundscapes that Sunday School embodies. Their insights unravel the collaborative energy and radical vision fueling this new event series, offering a glimpse into the creative forces shaping London’s underground scene.

Find more info and tickets for the main event and the afterparty by following the links.

We’ll start with the big question, why Sunday School? What was the main drive or creative need to kick this series of events back? I recall you mentioning you organised a first iteration back in Australia.

Dom: Sunday School as a concept and an event series is something that seems to have maintained an identity for the past decade. Originating as you mention, in Melbourne as a weekly punk and experimental Sunday afternoon event that I ran from the bar that I worked at, it has now taken on a new form as a bi-annual diverse all-dayer at New River Studios in East London.

The most current iteration of the event series, Sunday School III: End of Eternity, delves deeper into playful concepts of evil imagery and the occult. Imagine a traditional Sunday service setting—punk kids attending against their will, playing up, breaking the rules, and eventually turning to the devil (obviously). That kind of imagery is what comes to mind when I imagine the event and its curatorial approach. The idea is to work with serious elements of music and art but present them in a fun and new way—that’s the challenge!

In London, the event series came back into the picture in September last year as a fundraiser. Almost coincidentally, the only day the venue had available was a Sunday – so what better time to bring back the unholy gathering? I was raising money for my visa application at the time – something that had tormented me for the better part of a decade living in the UK – so to experience such a positive reception alongside a really good day, it only felt right to continue and develop the event.

You also mention that one of the main aims/urges behind the events is to create a more playful and less conventional atmosphere. What made you realise this is what you wanted for your events? What did you find lacking in the many other gigs/events you are a part of or attend as an audience?

Dom: I like the idea of turning a negative into a positive—a really stressful personal situation suddenly became a life-affirming group-led experience, and that is what’s given me the drive and motivation to continue organizing these events.

Overall, it’s a fun personal challenge to contribute to the musical landscape of London and offer a different approach to social events – celebrating individualism, diversity and the personal power that can be experienced by getting amongst it and resonating with the vibe of the people on the day.

In terms of how you envisage these events, you mention that the community comes first.

Dom: The goal is to create an environment where people feel excited to attend regardless of the lineup- where they can feel comfortable and experience wonderful and unique sound performances each time they attend an event. Like most subcultures and scenes, London is relatively small once you’re a part of it, and there are so many people across varying disciplines of music and art who are doing really interesting stuff. For me, it makes sense to encourage an element of cross-pollination and to have a general enthusiasm to build community within it – to bring people together who all hopefully share one unifying objective – do exactly what they want to do artistically and have fun and be supported in that

How then, do you prioritize community building in your event planning, and why is creating a comfortable environment for all attendees crucial to you?

Dom: I think creating the right tone for the day begins from the moment the show is announced. The lineup, the poster, the choice of language and the overall aesthetic. Showing through the way you communicate with your audience that the event welcomes everybody and is not exclusive to one certain scene or clique.

Talking more about community, what is your opinion on London’s current punk/experimental /electronic scenes? I’ve been observing a growing number of close-knit groups and communities, with a fair amount of cross-pollination and lots of energy and passion.

Dom: I think noise and punk are forever intertwined. Many people in punk bands have noise projects on the go which has been prevalent in every scene I’ve been a part of. They both share the same sentiment – have fun, express yourself, destroy shit – without really needing to know what you’re doing or how to play the instrument – historically, it’s ‘music for the non-musician’, and it’s what makes both styles of music so epic and captivating.

Many of my favourite London-based event organisers are involved in DIY cultures in some shape or form. Definitely keep an eye out for gigs from the likes of Cryptic Growth, Planet Fun, Earworm Presents, KAOS, and Club Mutante.

What strategies do you employ to ensure your lineups are diverse and inclusive and provide opportunities for artists who might not typically have a platform (this goes back to supporting the community mentioned above)? At the same time, the risk is being too eclectic, mixing up too many different audiences, and losing some interconnectedness and cohesiveness.

Dom: It’s always good to begin by not prioritising acts that play too often or are predominantly male-centric. Having a broad and diverse lineup is essential for a harmonious environment at shows, and for me, it’s important not to fall into old troupes of the same group of mates billed for each gig. I like to do my own research on what’s happening and who I think would fit the bill, but I also try to talk and meet people when I can, always appreciating recommendations when they come around.

In my opinion, research is good, but a gut feeling is better. It’s good to trust your first and most natural ideas and use your own experiences and instinct to strive towards the event you want to create.

It’s also good not to get too attached to one idea of how the event is going to look. Don’t lose hope when the band you really want says they can’t do it but rather look at it as a small stumbling block on your way to making the event you want to make. Be ready to reshuffle the lineup and see things from new angles – one of the greatest things about living in London is there are plenty of amazing artists to choose from – whether it be from London itself or other parts of the UK or Europe. And when you live somewhere like this – why not bring Russell Haswell down from Glasgow and pair him with the death rock/hardcore punk of Hellscape. I don’t care – it’s fun, so let’s do it.

Given your active engagement in diverse music scenes—punk, electronic, noise/sound—and your background in sound art, how does all this pan out and influence the events you curate? I guess one of the main advantages is the number of bands/artists you meet?

Dom: Definitely – having a good understanding of varying sound cultures is super beneficial – and even better when you’re involved and active in them. My first memories of living in London were more focused on sound art and experimental electronic music – because that’s what I was studying then. But as things progressed I became less inspired by the art world, and certain aspects of academia – punk, noise and diy band events emerged as something that was more important to me and has remained that way up until now. Having understanding both worlds definitely helps, and if there’s ever an opportunity to combine specific artists for lineups that exist within different musical worlds, then I’ll always try to make it happen and find the concept of doing random stuff like that’s really cool.

You mention you want to play with the idea of curation and create new and unexpected experiences for the audience. In what ways do your events challenge traditional notions of music curation and performance? Are there specific theories or artists that inspire this approach?

Dom: I like Luigi Russulo, the Italian futurist, and his 1913 letter ‘The Art Of Noises’. Russolo’s general enthusiasm for real-world sounds and his claim that day-to-day noises would one day be performed as the ‘orchestra’ have continued to inspire me, whether it comes to event curation or my own sound creations.

We must break out of the limited circles of sound and conquer the infinite variety of noise-sounds.

Can you elaborate on the influence of events like Creepee Teepee and Unsound on your curatorial approach? How do these experiences shape the way you design and execute your events?

Dom: I’ve always enjoyed the concept for these events and have been a regular at Unsound on and off for many years. The first time I attended Creepee Teepee, a smaller-scale festival in the Czech Republic, I loved the flow of the festival. I was amazed to learn of the intentional, non-flowing nature of some aspects of the curation. They would have a techno artist, followed by a Soundcloud rapper, and a Scandinavian black metal band. It was super cool, and that element of chance made the event more exciting for me. Unsound is a bit more mapped out with their events, but for Sunday School, my inspiration sits somewhere in between.

The role of a curator extends beyond selecting artists and piecing together an event that flows well; you mention, for example, keeping engagement with the artists throughout the process, discussing elements of the theme and getting the audience excited for a special performance. How do you engage with artists during the event build-up, and why is this interaction meaningful for the overall experience?

Dom: I think it’s essential to maintain a strong dialogue with the artists during the lead-up to the event. Not only about technical elements or general gig stuff but also to discuss any ideas they might have regarding their performance—and make sure you’re supportive in facilitating what they need. Also, talk through concepts of the theme and offer suggestions on how to integrate these concepts into their set.

For Sunday School III, the theme is inspired by one of Russell Haswell’s tracks, End of Eternity (released on Editions Mego in 2020). Could you expand on how or in what way this track resonates with you and why choosing it for this event?

Dom: Haswell has a unique charm in the way he goes about and creates electronic music. His approach is very much in the here and now, rather than getting caught up in the deliberating process of production or perfection. It’s primitive, and it’s chaos, and that playful approach to his music is essentially what encapsulates the spirit of these events. All the artists on the line-up have some element of rawness and experimentation in their sound. It’s essential; it’s a prerequisite. It’s definitely part of the essence of the event.

Haswell’s performances are characterised by their abrasiveness and extreme experimental noise abstraction. What can we expect in the context of Sunday School?

Dom: Hopefully, abrasiveness and extreme experimental noise. I guess another fun thing about Russ is you never really know. As much as there are elements of chance configured into music, the same goes for many aspects of his performance. Let’s see on the day!

Minerva, let’s talk about the zine; as an artist yourself, how have your background and interests shaped your vision for the project?

Minerva: I have always loved zines. Documenting and archiving is an extremely important part of the process in all creative endeavours; a zine’s purpose can be informative, playful, or a concise evaluation of a bigger project. I love the combination of imagery and writing when flicking through a zine, so I really wanted to have a good mix of both mediums for this issue.

What was the intellectual process behind this edition? (i.e., what were the main ideas you wanted to research and develop, and what was the main inspiration behind them)?

Minerva: I wanted to bring an equal mix of imagery and writing in all forms for this edition, and I think the artists have produced exactly that. We gave each artist only the title and let their artistic licence roam free; it’s essential to allow creative autonomy as too many constraints add pressure, and from my personal experience, that can alter the work.

How have you approached the artwork and artist selection for this edition?

Minerva: The selection of artists came naturally and easily, mainly through Instagram, a handy tool in a case like this. From the artists that have been selected, the depth you can get from an image compared to writing varies between individuals. This is why I think it’s vital that the theme includes both, ‘End of Eternity’ zine has got an extremely different response from each artist, and I’m really excited for everyone to see it.

Why do you think a zine is an interesting format to work with, firstly, from a more general artistic context, secondly to portray the work of the selected artists in the different editions, and thirdly, for Sunday school (as in an extension of a music event in this case).

Minerva: From my perspective, Dom’s main essence of Sunday School is a community event that brings together a variety of musicians to produce an eclectic experience throughout the day. The zine mirrors this, and having a physical embodiment of the day’s events, artists, and information for the event gives people the opportunity to not just leave with memories but also a special zine to look back on and look up their favourite artists from the event.

One of the main challenges promoters face nowadays is funding these independent events, balancing affordable events while affording high-quality artists/paying artists a decent fee. How are you navigating this challenge?

Dom: That is essentially the main challenge. The task is to book great artists while keeping ticket prices affordable- which is almost impossible for independent DIY events when entering the world of agents, managers, and all that industry stuff. From my experience, for smaller events, there’s a lot more importance placed on building relationships and selling your event in a way that’s appealing to the artist and their surrounding team. It’s far more about how you communicate and present the event rather than what it might be like for bigger-scale organisations, where it seems to usually come down to numbers and budgets etc.

How do you stay inspired and keep your events fresh and innovative in a rapidly evolving music scene?

Dom: Keeping an open mind and enjoying the challenges along the way. If you’re passionate about what you’re doing, it shouldn’t take long for the vision to fall into place, and from there, it can be sculpted, developed, and fine-tuned.

In general, I think the best approach to events or projects is to try and do your best, no matter how big or small the task. I think there’s something important hidden within the moments we consider mundane or a chore, and if you can get through the not-so-glamorous tasks and still produce great work, then everything else gets that bit easier.

And to end up with, looking ahead, how do you envision the evolution of these events? Are there any new concepts or collaborations you’re particularly excited about exploring?

Dom: I just really like the idea of pairing a theme with an event. I think it helps unlock people’s imaginations about attending an event and also offers a lot of potential for creating unique aspects within the event space. Thinking up the concept is also a bit part of the fun—researching and conceptualizing and then curating a lineup that will complement aspects of that theme, etc.