Interview by Lula Criado & Meritxell Rosell

In the dynamic world of contemporary art, the fusion of creativity and technology ignites a canvas where boundaries blend, raising endless possibilities. Leading this digital renaissance at the forefront is the Serpentine Arts Technologies Programme, a groundbreaking initiative by Serpentines celebrating its 10th anniversary this year.

With a central question in mind, how can artistic experimentation challenge and reshape new technologies’ role in culture and society? , the Serpentine Arts Technologies Programme thrives on dialogue, uniting artists and technologists in a vibrant exchange of ideas. It fuels innovation, creating artworks and theoretical frameworks that challenge our understanding of aesthetics and the human experience.

From immersive installations transporting viewers to otherworldly realms to AI-driven creations provoking deep introspection, the program is a hotbed of the avant-garde. This initiative allows a common ground for artists, technologists, and creatives to collaborate and reimagine art beyond traditional confines.

Two of the main driving forces of the programme are Kay Watson, head of Arts Technologies, and Eva Jäger, Arts Technologies Curator.

A curator and art historian, Watson possesses a profound curiosity. With a background that blends art history with digital culture, Watson’s journey into the realm of art and technology began during her academic years when she recognized the boundless potential of the digital domain to transform artistic expression.

Complementing this vision is Jäger, an artist and designer working with machine learning in her own practice. Jäger’s expertise giving ideas form breathes life into the most ambitious artistic dreams. Her journey commenced at the intersection of art and technology, where she uncovered the artistic potential of coding and using performance as an interface to it.

Together with an incredible team of creatives, such as Victoria Ivanova (Serpentine Arts Technologies Strategic Lead in the development of the R&D Platform and Future Art Ecosystems), they lead a role in redefining art in the digital age.

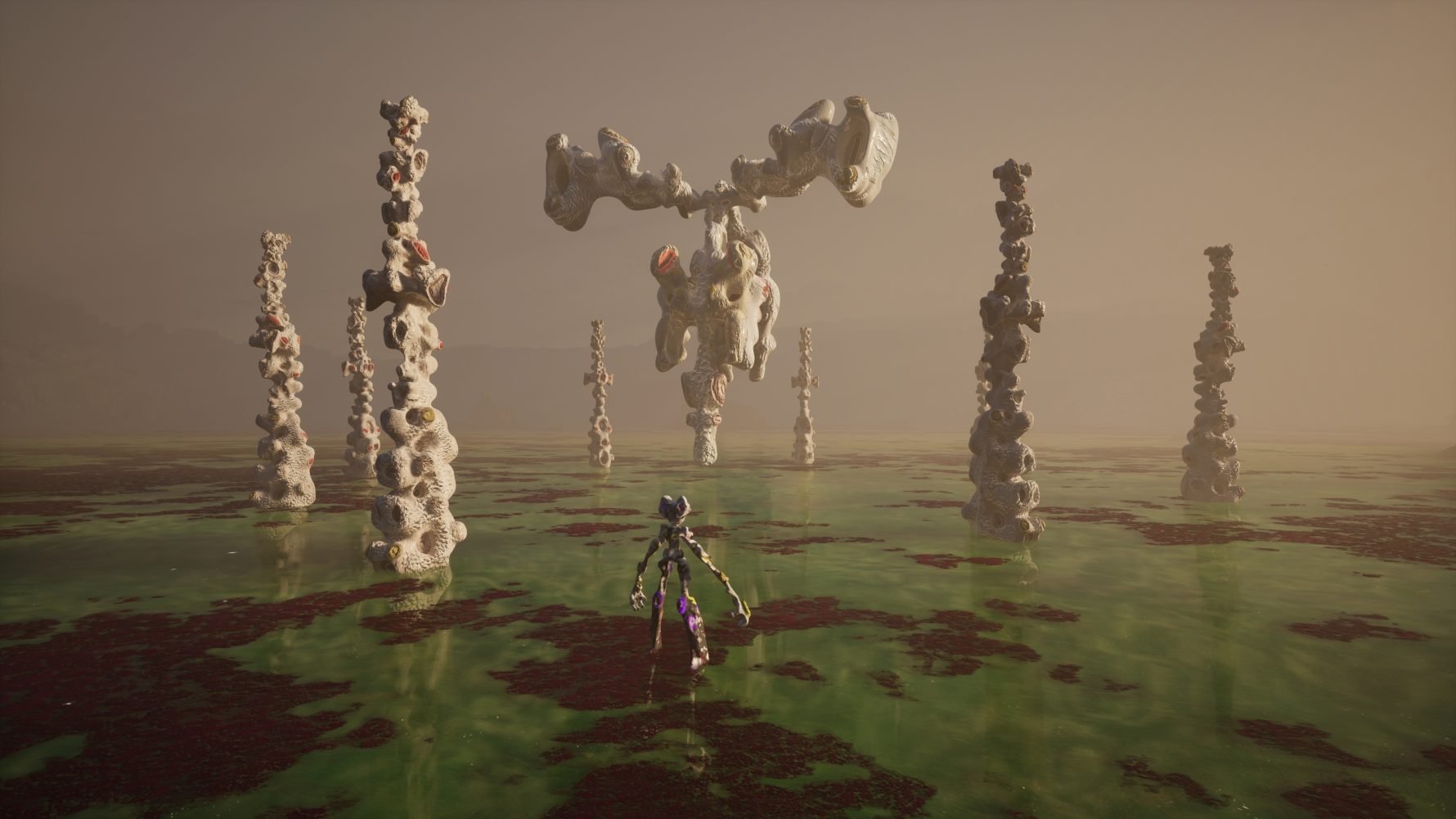

One of Art Technologies’ most recent multidisciplinary projects, Third World: The Bottom Dimension by Gabriel Massan & Collaborators, launched in June 2023 as a video game, a collaborative exhibition and web3 tokens powered by Tezos. The exhibition extends the ideas that have driven the creation and development of the mirroring video game.

It allows audiences to play the game in a communal setting around site-specific set design, sculptures, sound and films. Through the lenses of queerness and decentralisation, Third World aims to challenge the audience to rethink how we understand the world through ancestral knowledge, healing, ecological awareness, transmutation, and agency.

Watson and Eva Jager shared with us their individual journeys, some of the inspirations behind Arts Technologies, and the programme’s impact on the art world in a journey through the ever-evolving nexus of art and technology.

How do you think your personal backgrounds and past experiences shape and are reflected in The Arts Technologies programme at the Serpentine?

Eva: My background is working as a practitioner. Being on both sides (the institution and the artistic) helps me as a translator between the two vantage points. I feel like what I am helping to build at Serpentine is the kind of institutional partner I want to see for creative practitioners. It also informs my role as a curator: in our team, curators function as producers/technical managers, deeply embedded in the artistic team and part of the creative process.

Since our projects are complex and distributed, our work necessitates working collaboratively with many different practitioners. We all come from wanting to make things. The discourse and ability to prototype ideas within the art field have brought us to this work.

Kay: We’re a team of people with different kinds of experiences that have coalesced around art and technology. From my perspective, I bring experience as a playing and recording musician, as a digital and print archivist working with photography and as a (sometimes more traditional) curator and art historian.

Challenging and reshaping the role that technologies can play in culture and society is part of Serpentine’s commitment; From your perspective and experience within the Serpentine Arts Technologies programme, how do you see this role of the “art institution” in shaping and defining the core values of cultural production? What has been the programme’s reception and interaction with other institutions alike?

Kay: We’re extremely fortunate to be within an art institution that considers these questions to be, not only, important but considers them crucial enough to resource. The art institution as a public space for discourse, convening, narrative building and experimentation is so valuable and really important in dialogue with other areas of society.

Our department was born as a space to reconfigure how the institution engages with advanced technologies and how to bring artists into that engagement. One of the key tenets from the beginning was to keep production knowledge in-house to improve our organisation’s capability to support artists who work with these technologies and to stop that knowledge, expertise and value from being outsourced and therefore lost by the institution.

We moved from one-off projects to more deeply embedded research commissions. Another was the ability to support Creative R&D by developing a programme that could be a malleable space that could support more work that would be considered high-risk and without predefined outcomes, which is how the R&D Platform. It’s also about our relationship to the wider ecosystem and remodelling our part of the organisation to provide value to that.

A vital outcome of the R&D Platform and its programmes, including our R&D Labs and Future Art Ecosystems, is our growing relationship with our peers, from artists and technologists to organisations working with art and advanced technologies and the broader cultural sector, as we move forward the sharing of knowledge, skills and capabilities across the sector and ecosystem will become more vital to have lasting impact, particularly in the public sector.

Five R&D labs (Legal, Blockchain, Labyrinths, Creative AI and Synthetic Ecologies), a yearly report publication, live events, podcasts, and digital commissions; how’s the weight of each part of the programme decided and balanced?

Eva: We are an agile team and like all things, it’s about capacity, resourcing, the current context, internal programming across Serpentine and our relationship with partners and collaborators, but most important is to see everything as a holistic proposition, so the line between the R&D Platform and our commissioning work is becoming increasingly blurry.

The work of the R&D Platform is reconfiguring how we operate and we now think of it as a feedback loop and include other organisations with whom we exchange capabilities as part of that. For example, Future Art Ecosystems 3: Art x Decentralised Tech, the work of our blockchain lab that has been led by Ruth Catlow and Penny Rafferty since 2018, is been key to our knowledge (in addition to the broader ecosystem, of course) and these learnings will then be embedded within the organisation from our strategy for non-fungible tokens (NFTs) to how we collaborate with other organisations, so everything is producing know-how that can continue to be built on and applied.

Kay: When we decide which artists to work to find practitioners we can collaborate with in the long-term who consider their work in a similar way to the way we operate- larger scale, durational research projects—working with artists like Trust, Gabriel Massan and Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley, their practices lend themselves to plugging into distributed organisations that share certain goals with them.

A prominent focus and interest across the Arts Technologies programme is gaming. Games were not much more than time killers and competitive electronic games; however, over the past 20 years, video games have begun to shift in purpose and use, with a clear impact on the art scene in recent years. On the other hand, film critic Roger Ebert publicly battled against the perception of video games becoming art from 2006 to his death in 2013; video games have yet to be fully recognised as an artistic medium. What are your thoughts on the topic? And a step further, how do you think video games are changing the narrative of art?

Kay: This particular area of focus comes from the fact that the infrastructure of gaming is what powers so much digital work, as this is a major driver of society-wide infrastructure when it comes to CGI, virtual environments, interactive mechanics and so on. These ideas also formed part of our strategic briefing in 2021: Future Art Ecosystems 2: Art x Metaverse.

Games have always had cultural value though the contemporary art establishment has ignored them for decades. We aren’t arguing for video games to be absorbed by the art world, but something is interesting about a generation of artists who can and want to make games. This also isn’t new, we can look at the work of someone like Rebecca Allen, an artist who has worked between the art world and the tech research space since the 1980s, who was brought into Virgin Games in the early 1990s as a ‘3D Visionary’ to support the 2D to 3D transition taking place at that point.

She was developing games with contemporary visual artists then, even though they did not see the light of day due to rampant misogyny within the industry. So, she built her own game engine to make simulations as part of her artistic practice in the mid-1990s. It was really the pandemic had a huge impact on the perception of video games (not only in the art world but in general) which has really been able to lift up some of the work we have been making since 2013, from Ian Cheng’s B.O.B. to Hivemind by Trust.

Apart from the possibility of new narratives and time-space dimensions (like in Hivemind), what other gaming features are you exploring, or do you think could be relevant for artistic expressions and/ or interactions?

Eva: We are interested in the increasing use of game engines to simulate real-world scenarios for the purpose of training computer vision systems. This is something that the R&D Platform is researching together with Creative AI lab, Coventry University, and Alan Turing Institute with the artist duo dmstfctn under their larger project GOD MODE: EPOCS. The interesting part of this work is that it’s all about user testing and creating interaction with the audience; it aims to reveal the characteristics and limitations of this synthetic reality.

In GOD MODE (ep.1), the performance was set within a real-time simulation of a supermarket, a replica of those used to train AI to navigate 3D environments and recognise items on shelves for use in cashier-less supermarkets, like Amazon Fresh. The simulation is rendered in real-time and is navigated by the artists, who also perform facial motion capture and voice modulation of themselves to animate the AI on screen. The audience participates in the training by interacting with the simulation on their phones.

The Creative AI Lab, a collaboration between Serpentine R&D Platform and the Department of Digital Humanities, King’s College London, aims to offer a space to engage with advanced/deep machine learning technologies critically. Regarding AI aesthetics and the premise that the Lab follows, it seems we are at the early stages of understanding the aesthetics and semiotics of AI. What direction or position the creative AI lab has established or wants to establish itself in? And how are the artists challenging some of the aesthetic uniformity/biases/predictability of these trained machine intelligences?

Eva: With the advent of new generative AI tools purported to automate the core role of the artist–we have to step back and consider what role we actually want the artist to play. At the lab, we have been less focused on specific tools per se and more drawn to looking at artists who build complex AI systems or systems that employ a wealth of new tools, including AI/ML, blockchain, etc.

These practitioners go beyond ‘prompting’ to build systems that engage AI/ML’s conceptual, practical and political implications. We see that the specific functionality of AI/ML will reconfigure rather than replace the artist’s work, becoming only one part of an increasingly complex constellation of methods and technologies.

The Future Art Ecosystems (FAE) is an annual strategic briefing that provides analytical and conceptual tools for the construction of 21st-century cultural infrastructure: the systems that support art and advanced technologies as a whole and respond to a broader societal agenda. What have been the main outcomes and the responses to releasing these briefings?

Eva: the latest Future Art Ecosystems 3: Art x Decentralised Tech (FAE3) came out in November 2022. The FAE series was born out of a need to inform ecosystem design for art and advanced technologies (AxAT). It’s an annual strategic briefing produced by Serpentine’s Arts Technologies (and many contributors from the cultural sector and beyond) for crystallising the dynamics and opportunities within the emerging technology spaces for building 21st-century public cultural infrastructure: the systems required to produce, distribute and financially support AxAT practices that are responsive to the most urgent techno-social issues of our time.

It’s also key that this strategic thinking is borne from the public cultural sector itself for its own benefit rather than from the commercial or private sector, which ultimately have, at least partially, a different set of goals and visions for how technologies become embedded within our public life.

Kay: Since 2019, FAE has united and platformed the voices of leading artists, technologists, cultural organisations and civic actors, whose efforts are directed towards building out new systems that can drive organisational and creative innovation with regards to AxAT. The last briefing identified new organisational and creative innovation patterns within the broader space of decentralised technologies, variously dubbed as ‘web 3’, ‘crypto’ and ‘dweb’.

Through interviews with specialists across art, web 3, crypto, dweb, innovation policy and civic, we proposed a series of prospective strategies for existing and new cultural organisations interested in AxAT and the latter’s role in supporting resilient, democratic societies.

What new technology or scientific development are you most excited about seeing being used in an artistic context?

Kay: I think this is something that excites us in general as it’s at the centre of what we do every day, whether it’s commissioning or research because artists interrogate developments, and essentially turn our preconceived notions of these developments on their heads, is really so valuable.

What would be your biggest curating extravaganza?

Kay: A multi-organisation, multi-artist, multi-platform interoperable collaboration in which we share our capabilities with others 🙂

You couldn’t live without…

Kay + Eva: Good colleagues!