Interview by Hannah van den Elzen

The interdisciplinary artist Miloš Trakilović primarily works with digital media, translating complex theoretical ideas into sensorial experiences. And this goes beyond mere spectacle – by carefully considering how moving images unfold into physical space, the artist extracts the narrative core of a work (which, according to the artist, can sometimes be theoretically dense, complex or profoundly straightforward) and materialises it spatially. Through his work, the artist evokes a sense of complicity and a feeling of involvement from the audience, allowing viewers to experience his work in a bodily manner.

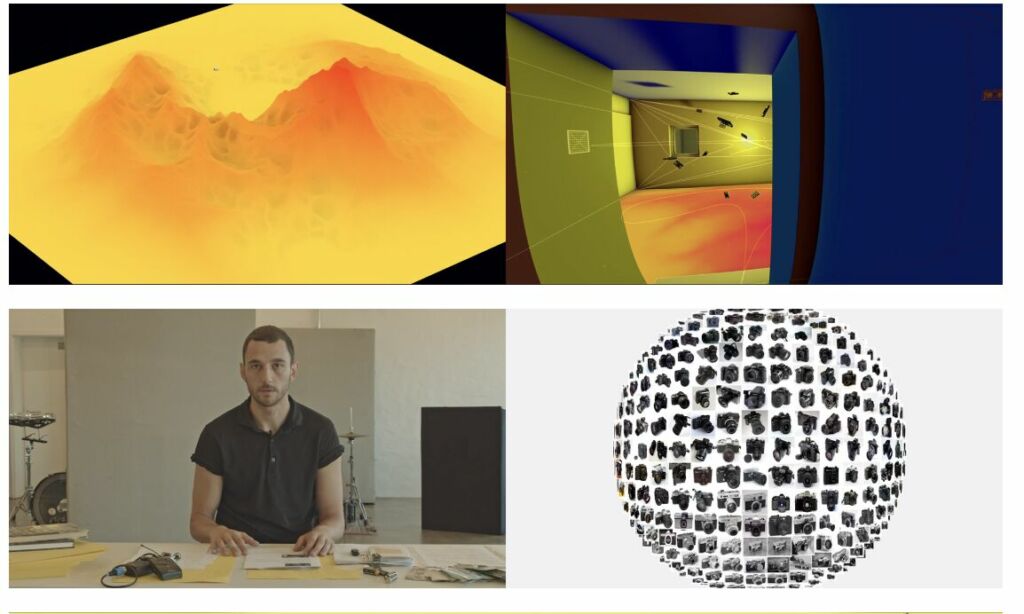

Miloš Trakilović currently presents his body of work, 564 Tracks (Not a Love Song Is Usually a Love Song), in the exhibition Emerging Exits, located in a historic bunker in Arnhem, the Netherlands. Here, the artist resembles a scorched production studio through a six-channel sound installation (algorithmically controlled and generated in real time as a process-based composition), a four-channel video (real-time, audio-responsive) environment, and architecture made of charred wood, releasing a distinct burnt scent, while the screens display hallucinatory, audio-reactive visuals illuminating and animating the room in the monumental bunker.

The installation interacts with its location, the monumental Diogenes Bunker, because Miloš Trakilović’s body of work links digital perception to contemporary warfare. The artist is intrigued by the digital age, in which perception is affected by the clandestine, proprietary and highly extractive mechanisms underlying many of the technologies we use on a daily basis.

Miloš Trakilović grew up during the Bosnian War (1992-1995). After the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, the Cold War appeared to have ended, yet in Yugoslavia, the political and ethnic tensions were intensifying. These tensions led up to the War, marked by mass expulsions and the genocide of thousands of Bosnian Muslims. In his work, Trakilović suggests that the impending crisis in Yugoslavia after the Cold War might already have been audible in the songs preceding the war. With AI, the artist created a tool to test this hypothesis, reading data from the past to make sense of the present and its patterns, which point towards a possible future.

Grazer Kunstverein installatiohn view (2023)

Your installation, 564 Tracks (Not a Love Song Is Usually a Love Song), links digital perception to contemporary warfare. How do you see its mediatization and its enduring traces?

The Bosnian War, in which I was born, was one of the first conflicts to be massively live-mediated. It was broadcast globally through centralised television networks. Those images became inseparable from my own childhood memories, which made me question from an early age onwards how conflict is being framed and circulated. Today, that logic has only intensified: we witness wars unfolding through algorithmic feeds that personalise and fragment our perception. Conflicts are mediated more instantaneously than ever, but that doesn’t mean these images reach us with the same intensity.

Your practice explores the politics of perceptibility, addressing themes such as memory and loss. All in relation to the aftermath of the digital turn: in your view, how do technological developments transform human perception?

What was once understood as the politics of representation—the question of what and how things are made visible—is now being reconsidered in light of profound paradigm shifts. Today, it is not only about how things come into being or are rendered visible, but also about how they are actively rendered invisible or kept unseen.

In my view, perception is not merely a subjective process of acquiring, registering, interpreting, selecting, and organising sensory information. It also concerns the ways in which information is or is not made accessible to our senses today. As an artist and researcher, I am interested in the power structures behind these processes, as well as in the political realities that emerge from them.

564 Tracks (Not a Love Song Is Usually a Love Song) suggests that the impending crisis in Yugoslavia after the Cold War might have already been audible in the songs preceding the war. Do you believe sound can reveal something about historical or social tensions before they become visible?

There are numerous existing scholarships available on this topic. I was inspired by Paul Virilio’s observation that sound inherently reveals the future, as it almost always reaches us before anything visible enters our perceptual field. Similarly, the Italian Futurists from the 20th century incorporated industrial and mechanical noises into their compositions to explore how music can foretell social and political conflict.

In 564 Tracks (Not a Love Song Is Usually a Love Song), I draw on the interregnum period preceding the outbreak of the Bosnian War in 1992. After the fall of the Berlin Wall, a palpable sense of dread prevailed throughout the former East, but nobody knew how things would unfold or could fully grasp the violent dissolutions that would ensue.

I wanted to test the hypothesis that the war could have been anticipated or foreshadowed in the cultural production of that time. The statistical lens of AI revealed an increase in those tonalities leading up to the outbreak of war. I embraced this experimental approach not only technologically but also conceptually – revisiting the atmosphere of a society on the brink of disaster evoked unsettling parallels with the present moment.

How did you create the AI model for 564 Tracks (Not a Love Song Is Usually a Love Song)?

The process involved two custom-trained neural networks. The first was trained on an extensive dataset of warfare sounds – some originating from Bosnia, others from more recent, digitised conflicts such as Ukraine – encompassing a broad spectrum of sonic material, including sirens, artillery, drones, and ambient tension.

Once the model learned to detect these tonalities, it was applied to an extensive database of Yugoslav music, spanning the period from the fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989 to the outbreak of the Bosnian War in April 1992. It calculated correlations through a complex set of metrics, focusing on tonalities with a 60–80% similarity rate. Ultimately, it extracted fragments from a total of 564 tracks – hence the title – of popular music from that period. I stripped those fragments of their vocals, as I wanted to work specifically with the sonic atmosphere of the time. The first model served as the input for a second model that reconfigured and synthesised these fragments according to the melodic logic of a love song.

The result is a continuously evolving, processual composition — an unsingable love song — that never repeats in the same way; it can sound dark and sinister at times, and at others, it’s more melodic and tender.

What would you say is your chief enemy of creativity?

To me, it is often bureaucracy. Although you could argue that there is a dose of creativity in nearly all aspects of life, I don’t believe creativity can be the solution to everything. When I narrow it to the context of my art practice and art-making, what limits creativity is often the saturation with bureaucratic obligations inherent in running an art practice or securing resources necessary to realise a work.

You couldn’t live without…..?

Poetry.