Interview by Daniel Silva

Peter Burr is an American artist who explores the complex relationship between technology, society, and the natural world. One of his most notable works is BOOM TOWN, a virtual neighbourhood built entirely on the blockchain. This piece is a commentary on how technology is changing how we interact with each other and how it is creating new forms of value and exchange.

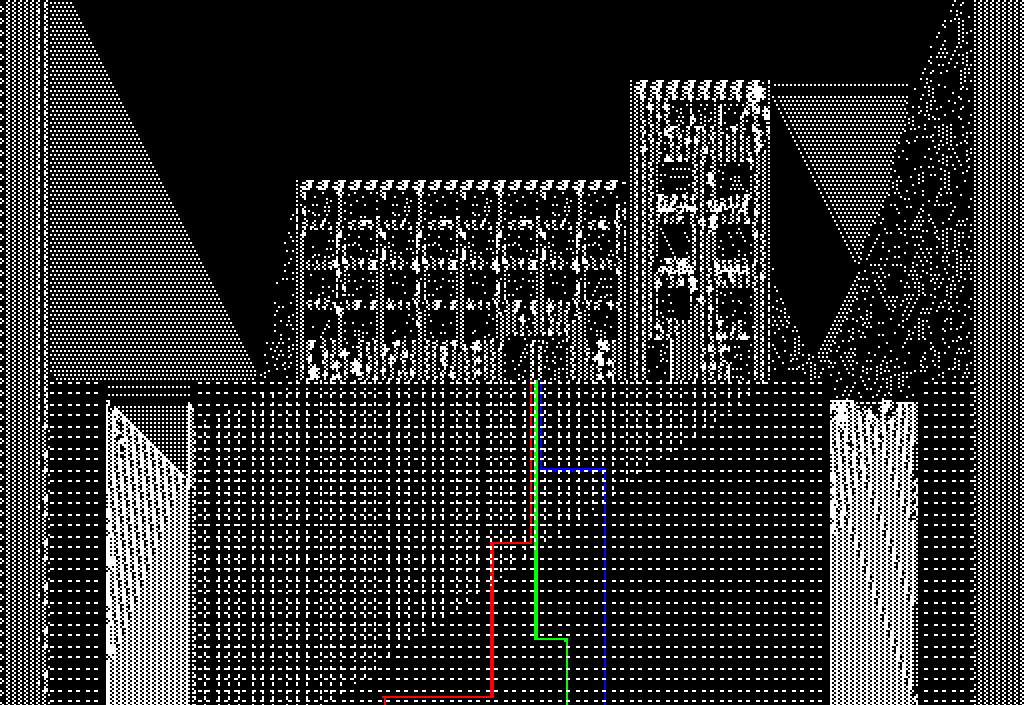

Burr’s artistic practice often engages with tools of the video game industry in the form of immersive cinematic artworks, and his works often feature intricate, surreal animated sequences that challenge the viewer’s perception and understanding of the world. Burr is also interested in how humans interact with the natural world and the impact of technology on this relationship. He creates complex, immersive digital landscapes that evoke the beauty and complexity of the natural world.

Collaboration and community are also key themes in Burr’s work. He often works with other artists and creatives to create complex, multi-layered projects that explore various themes and ideas. In this sense, his work is part of a more significant movement in contemporary art that seeks to create new forms of social engagement and collective action.

Respected curator and organiser Burr has curated numerous exhibitions and festivals worldwide, including the Cartune Xprez series. His innovative use of technology, engagement with social and ecological themes, and deep engagement with the history of animation and video art make him an important figure in the contemporary art world.

Burr’s works challenge our perceptions of reality and highlight the impact of technology on our lives. His collaborative approach to art-making is part of a more significant movement in contemporary art that seeks to create new forms of social engagement and collective action.

How did you first become interested in the arts, and what led you to pursue a career as an artist?

I went to Carnegie Mellon University for undergrad, a school with expensive technology and radical professional discourse. I grew up using computers, but I needed something to the magnitude of my access at CMU. Initially, I studied painting and enjoyed putting much labour into each image. I gravitated toward time-based work partly because of the labour involved. After discovering After Effects as a tool to collage things I found on the Internet, I got excited about using the media I grew up on—the games, movies and television—and reversed this firehose of mass media by switching from full-time user to full-time maker. There was something cathartic about it.

After CMU, I started the video label Cartune Xprez, born from my connection to the Bookmobile Project: An Airstream trailer that took yearly curated zines and publications on tour. I joined this project in the early 2000s and ran it with a group of artists and activists from North America. One of the core goals of that project was to take art forms and ideas confined to a small output (in this case, we exhibited zines and artist books) and distribute them to a larger community.

My former interests in animation, performance, installation, and my exposure to the Bookmobile Project, made me realise that instead of making work for film festivals, I could create my mechanism and take the work on tour. So, I started Cartune Xprez, a touring roadshow. As a result, my work became intertwined with a community of artists who worked individually with a sensibility of bridging high-brow and low-brow cultures.

A decade ago, my life and work flipped upside down. There were so many factors in my community. I realised my practice wasn’t serving the person I was becoming, so I took a break. When I reemerged, my practice led me towards making the work you see in BOOM TOWN.

Can you tell us about your creative process and how you approach the development of new works?

Earlier in my practice, I used digital tools to collage different sets of imagery, but when this strategy no longer served me emotionally, I had to shift the goals of my work. After a healthy break from my practice in which I had begun Freudian psychoanalysis (and was encouraged to dig into older aspects of my life), I thought a lot about the first tool I used to make digital graphics: a software called MacPaint on a black-and-white Macintosh computer. So, I started to make drawings using a MacPaint emulator and got excited playing with different fill patterns. There I saw a formal continuity between the maximalist collage work I used to make and the much more sober work coming out of this MacPaint doodling. Over time I taught myself to translate these tools into more contemporary technologies.

Your works often address themes of architecture, spatial relationships, and the intersections of technology and culture. How do these different interests inform your practice?

I like the idea of people finding their way out of their problems. A few years ago, I came across the book Pattern Language by Christopher Alexander, written in 1977; it indexed a system to help ordinary people solve complex design problems – like building a functional city for themselves, for example.

Living in New York, the challenge of using such a utopic self-help book got to me, and as an artist working with computers, I like playing around with these design concepts. There’s a hubris to the sort of power we taste when building dynamic simulations rendered realistically on computers. I can’t help but reflect on my lived experience as if I were one of these simulated units. Who are the people who hold the power to design the system I live in IRL? Where does my well-being fit into their conception of this world?

You are also doing a PhD in video games. Please share with our audience what you are focusing your research on. And where will it take your practice?

I’m interested in ‘worldbuilding’ – especially how this term means different things in different disciplines. For my PhD research, I’m diving into the world of Games to think about what the practice of worldbuilding offers people in the world of Art who are interested in building things we haven’t seen before.

Can you describe the concept behind BOOM TOWN and what inspired you to create a fictional neighbourhood on a blockchain platform?

I like the idea of using social technology, like blockchain tech, as a space for collaboration. A few years ago, I participated in a project conceived by Casey Reas called A2P that ended up being an early prototype of Feral File – working out the kinks of how this technology could work within our artistic community. So it’s an honour to bring BOOM TOWN into this space now that a few of A2P’s wrinkles have been ironed out and renamed Feral File.

Exploring ideas of empty spaces, something that you have done in other projects, how does “Boom Town” challenge traditional ideas about the function and purpose of architecture or address themes of urbanism and gentrification that are relevant to contemporary society?

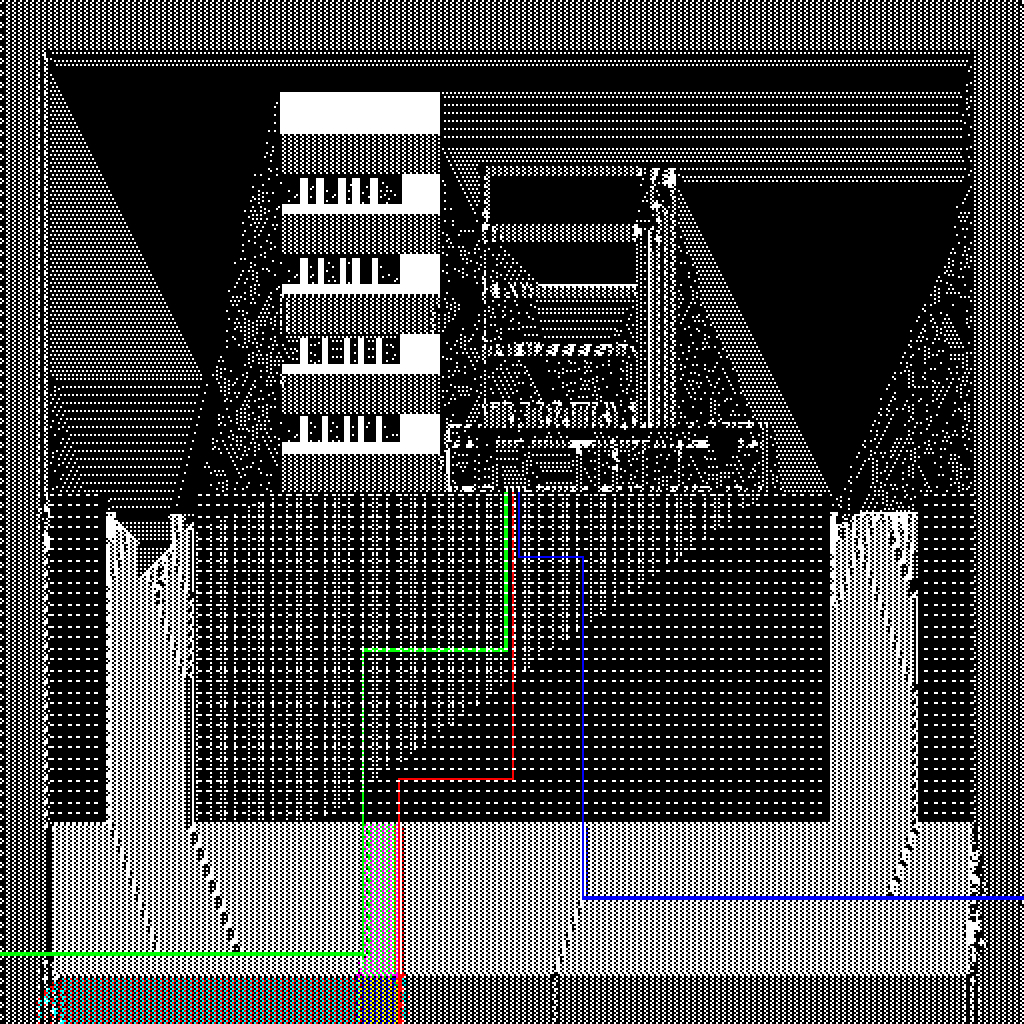

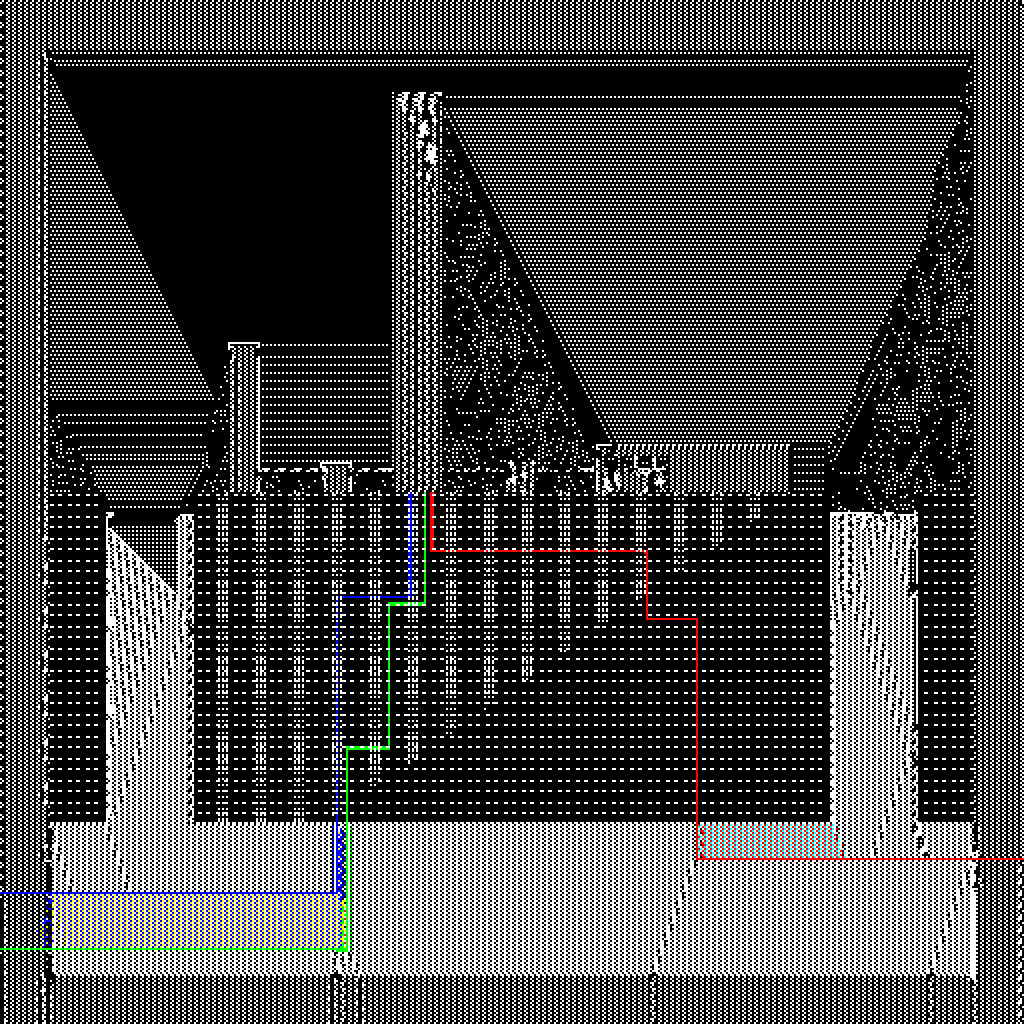

I think Julia Kaganskiy, this exhibition’s curator put it well when she said: BOOM TOWN is galvanised from the landscape of the American West, when makeshift settlements, or “boom towns”, sprung up wherever valuable resources were to be found. Informed by the ideals of Manifest Destiny, colonialist expansion, and get-rich-quick schemes, these towns attracted prospectors, speculators, and those in search of a fast track to a better life. On day one of the exhibition, BOOM TOWN is little more than a collection of empty structures, yet through the process of collecting, the town becomes populated and inhabited, in a sense, by the proprietors of its NFTs. At a time when Web3 is still, by and large, a vacant space to be developed and designed, Burr seeks to underscore that we will come to determine what kind of social and civic life it will ultimately enable and support. Not only will we be the ones who come to populate and activate these spaces, to breathe life into them, make them vibrant and give them their unique character and vibe, but the most potent promise of Web3 is that we can choose to build them differently, with a different set of principles and values.

How did you use blockchain technology in BOOM TOWN, and what challenges did you face in integrating it with your art?

Each artwork is built with a little clock that ages the piece. I hope that the piece will last for ten years and change multiple times over that decade. Will BOOM or BUST? It depends on people continuing to use this technology and writing on that cryptic ledger to move it forward.

What do you hope visitors will take away from their experience of exploring BOOM TOWN?

It will encourage visitors to slow down time and sit with the project for a while, if not the whole decade of its lifespan, perhaps for a few weeks or months. In a landscape of hyper-speed hyper-change, BOOM TOWN holds a possible hyper-antidote.

What is your chief enemy of creativity?

Burr clicks into chat mode, wondering if creativity does, in fact, have an enemy. “As an AI language model, I do not have feelings or emotions, so I do not have an enemy of creativity. However, some factors that may hinder creativity in individuals include fear of failure, self-doubt, lack of inspiration or motivation, distractions, and pressure to conform to others’ expectations.”

You couldn’t live without…

N/A.