Interview by Belén Vera

Despite beginning her artistic career as a visual artist, Susana López, AKA Susan Drone, decided to slide into sound creativity and experimentation. The result is a compact body of work shaped by soundscapes materialised into eight albums.

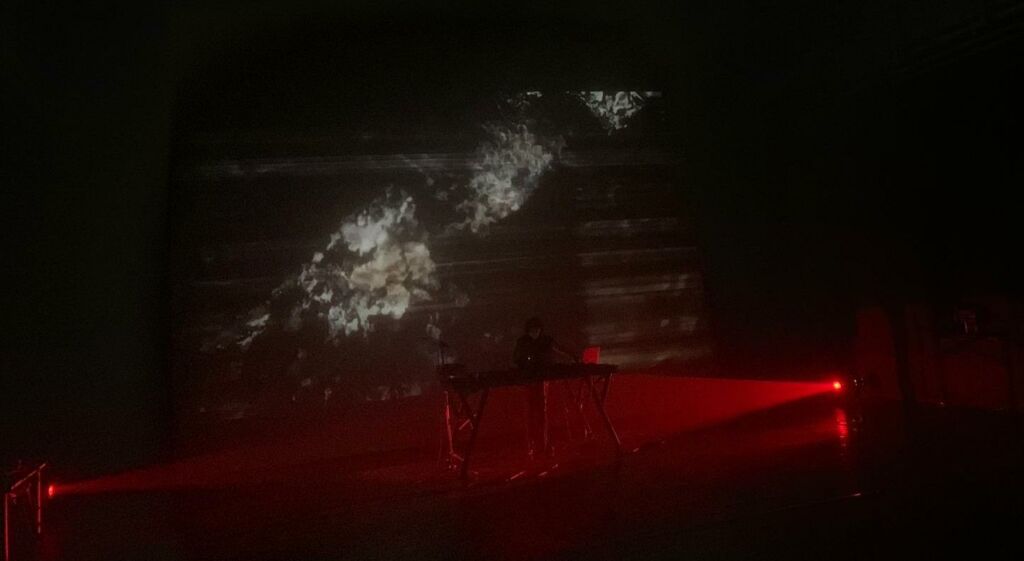

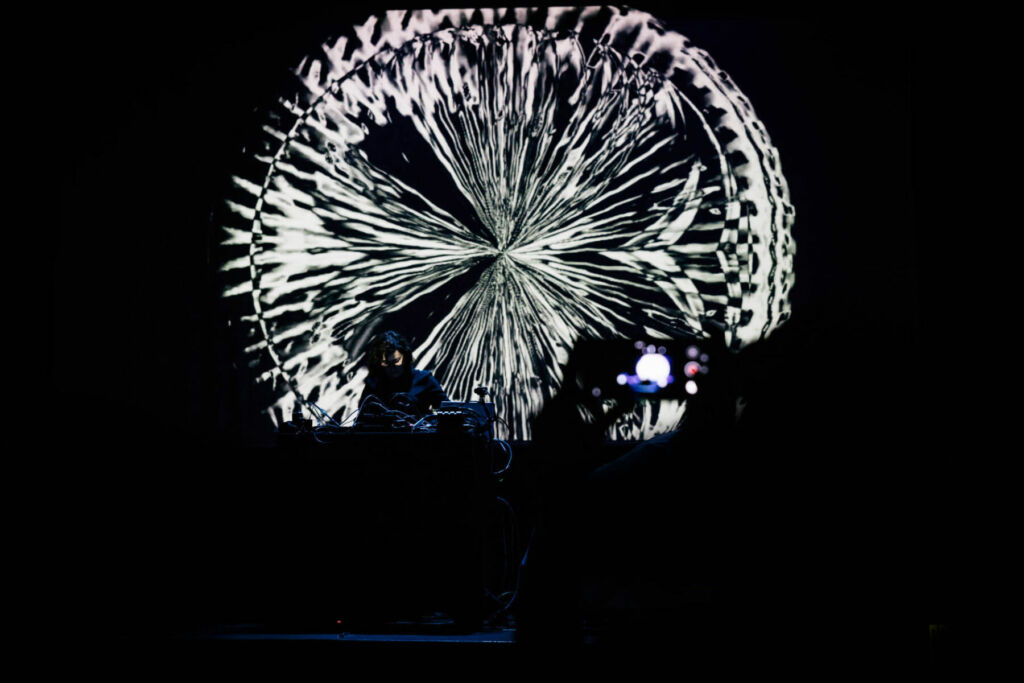

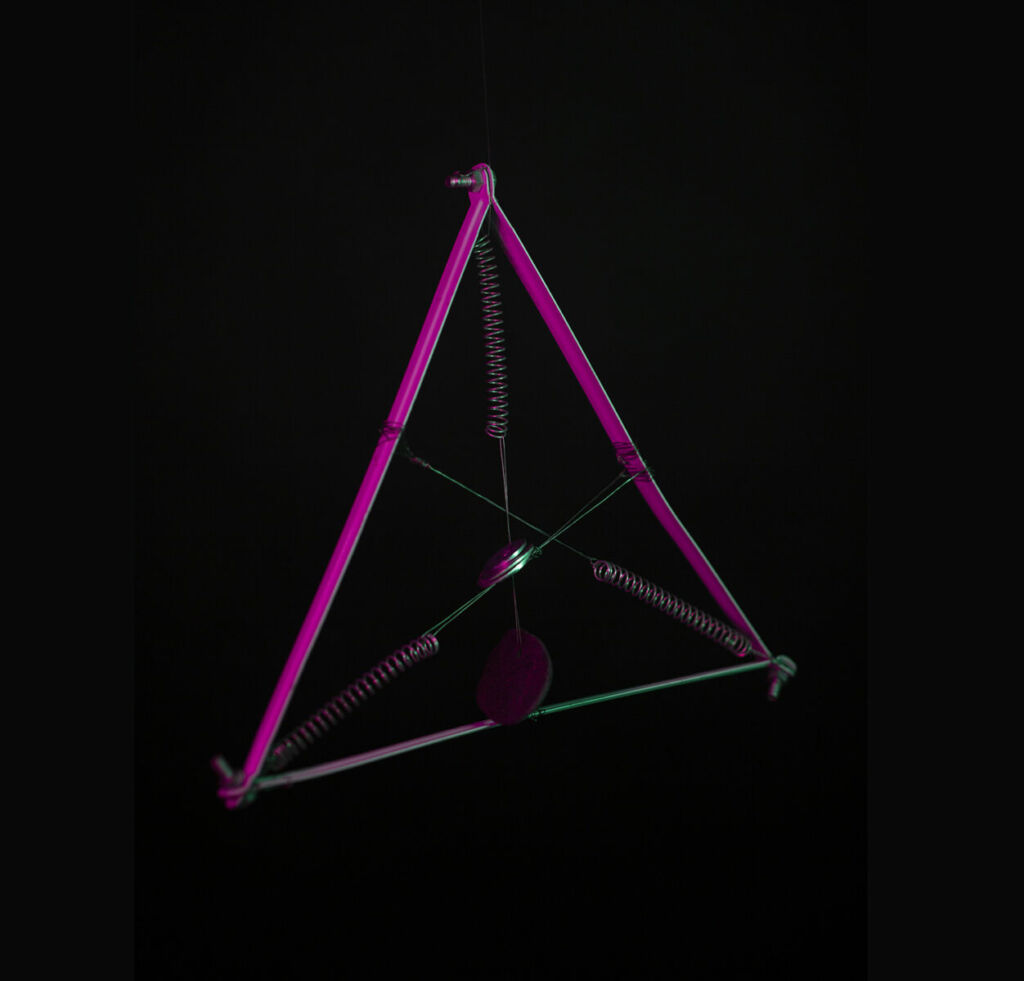

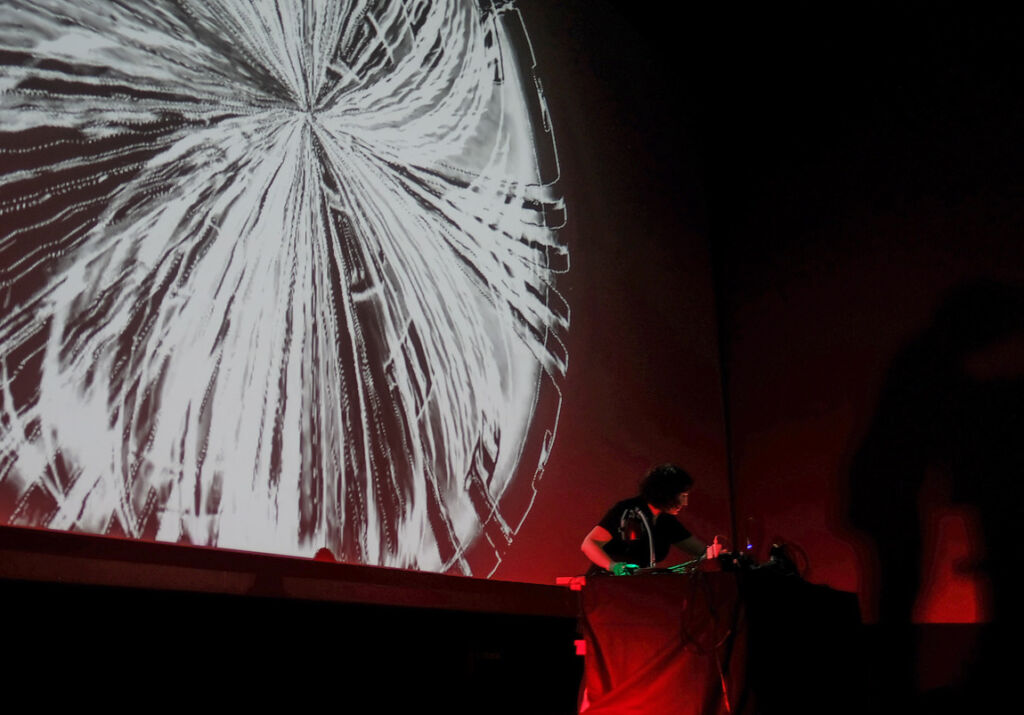

Drone’s practice is based on the manipulation of both sound and light, transforming our perception of space; at the same time, she creates new realities with a special intention in the materialisation of the unseen. Her pieces develop in an experimental dimension through drones and open-source software such as SuperCollider and with the use of field recordings, electronics and layers of vocal harmonics, which create dense clouds of hypnotic sound. Experimental, electronics, ambient, drone and post-minimalist music are her areas of specialisation which she carries out by reconstructing raw material through electronic processing.

Her work as a researcher put her at the front of coordinating the Sound Archive of Experimental Music and Sound Art, SONM, for more than ten years, curating sound installations and performances. She has performed live in many sound art festivals throughout Spain and Europe and launched her own podcast, “Noise Politics”, where she analyses the relationship between sound experimentation and ideological militancy.

As expected, her sound work did not divert her away from her visual facet, signing all her albums’ covers and live visuals and working on the visual art for music bands like Schwarz, Artificiero, Farniente, Mist, and Thomas Bey William Bailey.

Her album Crónica de un secuestro (Elevator Bath), was included in the Top Ten Drone in 2020 of the prestigious American webzine A Closer Listen. This was the result of a series of reflections and feelings around the idea of lack of freedom caused by the drastic measures imposed by the Government during the pandemic. The piece conveyed some sense of darkness and claustrophobia, a feeling that lightened up a bit in her 2022 album, The Edge of the Circle (Elevator Bath), where she created an expressive sound cycle of mythic archetypes and rich symbolism, a highly compelling piece of dark ambient artistry that welcomed the return of the fascinating composer.

Her last and eighth album, Stupor Mundi (Vestíbulo, 2023), juxtaposes digital drones with soundscapes. Here, she resorts to transformed field recordings, deconstructed drum machines, humanised synthesisers and synthesised voices, resulting in a dark body of work in which sounds hide behind immersive light and dark visuals.

Susan Drone creates a work charged with loops and drones, and whose cycles of reiteration that alter our state of mind. A perfect blending of organic and electronic materials that hypnotise us and take us to another world.

For those who don’t know your work, what can you tell us about your artistic practice?

As a sound and visual artist, I am particularly interested in audiovisual creations that allow me to explore the relationship between sound, light, space and time, more specifically, in transforming reality through the blend of these intangible materials, which act as catalysts, focusing our consciousness and altering our perception. My practice embraces hybridising sound creation with other disciplines, such as installations, performances, or video art.

I understand creation as an internal journey motivated by the desire for knowledge, to go beyond the obvious and a desire to materialise the invisible. The sound experience enables multiple dimensions of physical reality through perception.

Your beginnings started in the visual arts; however, your evolution as an artist has been directed more towards musical experimentation, producing sound installations and performances. At what point did you come across music and decide to place it in the central part of your work?

Musical experimentation has always been present in my life, I remember being at home with my sisters playing with a boom box (radio cassette), recording and making sound effects, scratching and hitting the microphone; we were doing Foley without knowing it. Later on, I worked on real-time visuals for other musicians’ concerts. It was pure synesthesia. I played music with images.

Once I realised I could create sound in the same way I created visuals, I started incorporating sound into my own work. I recorded my own material and then I transformed it. In fact, the process was the same that I had been doing for many years: transforming reality.

To create my sound works, I applied the same methodology I had previously used with video and image. Still, this time with the sound material: molding, sculpting and transforming sound was a natural process in my artistic career.

Visual creation has a great weight in your performances and installations. Tell us about your methodology and the creative process, both visual and sound.

My creative process starts from a sound investigation with an experimental dimension, guided by a form of ambivalence between the micro and the macro. Transformed nature is present, its shapes and sounds; mathematics (SuperCollider) and harmonics (drones); attention span and sensitivity to differences within the apparent similarity; extensions of time and alterations of space.

I usually create long pieces -between 10 to 20 minutes-, with sounds of slow and gloomy movement. A whole declaration of intent against the modern world, I believe the participation of the listener is necessary to enjoy and/or experience the transformation.

For the visuals, I use the same method as for the sound composition and video recordings that I later process. I try that in the final result, the material from which they come is not evident. I like to manipulate the concrete material until I get a different, abstract material.

Throughout your career, you have dedicated yourself to investigating sound art, specifically that created by women. What have these investigations contributed to your own work? Do you think there are nuances that differentiate experimental music created by women?

Artists like Eliane Radigue, Pauline Oliveros or Laurie Spiegel have given me the confidence to develop long-lasting pieces with very subtle note changes. They have also helped me listen to the world deeply, consciously and almost meditatively.

Answering the second question, no, I don’t think there is a difference between the music created by men or women; there is only a difference between people; each human being has a different background and experiences and that is manifested in their creation. When in 2009 I began working on the documentation and digitisation of the Sound Library of Experimental Music and Sound Art of Murcia, I discovered a large number of experimental composers who were totally unknown to the general public.

I decided to create an archive with all of them to make them known at a popular level, to vindicate their sound work carried out in silence for many years, and that was used by other male artists who never recognized them. I created some podcasts of this: http://susannalopez.com/women-in-experimental-music.

Your musical philosophy seems to be very much in tune with the idea of Sounding and Deep Listening and the meditation of Pauline Oliveros. Tell us about what inspires you.

For me, art is an inner search, a spiritual path, if you want to call it that. The act of creation establishes a parallelism between the search for one’s own being and vocational expression. Paraphrasing Friedrich W. Nietzsche in Thus Spoke Zarathustra, “the creative act as the only form of liberation”.

As you say, my sound creation is inspired, among others, by Pauline Oliveros’s Deep Listening as it explores the difference between natural listening and voluntary listening, conscious listening. By mindful listening, I mean a listening experience that has the capacity to communicate abstract content beyond aesthetics and to produce an exchange of energy that has transformative potential. Emotional, intellectual and spiritual.

I’ve also been influenced by drone pioneers and minimalist music such as Hildegard Von Bingen, Steve Reich, La Monte Young, Zoviet France, Tony Conrad, William Basinski, Charlemagne Palestine, Eliane Radigue and Laurie Spiegel; non-regulatory creators such as Isidoro Valcárcel Medina or Genesis P-Orridge; free musicians like Víctor Nubla, Laurie Anderson, Asmus Tietchens and Ianis Xenakis, among others.

On a visual level, my inspiration comes from masters such as Bill Viola, Abbas Kiarostami, Kenneth Anger, Maya Deren or Stan Brakhage and, of course, also readings by Ibn Arabi, Carl Jung, Nietzsche, Emile Cioran, Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir and Jacques Attali.

Your work also extends to the use and development of open-source software such as SuperCollider. What does computer programming contribute to your work?

Computer tools and programming code are the fundamental basis of my work. At the production level, I have always used the computer for algorithmic composition with SuperCollider; edit and process the audio with Reaper or Ableton; and generating digital modular sounds with VCV Rack or new creation with MaxMSP… It provides the most important thing, the possibility of transforming reality into a new digital world.

Anything crazy that you have come up with regarding the music that you would like to carry out?

I would love to do a concert in a cave using the reverberation of that space, it is the perfect place for prolonged listening, motionless in the darkness of a large cavern. I’m working on it.

In your research you compare the experimental musician with artists belonging to movements and subcultures such as Dada and Punk, coming to place it as the epitome of the anti-musician. Can you develop these ideas further?

These ideas were the basis of my investigations in The Politics of Noise. Noise as the ultimate weapon, in them I analysed the origins of underground music as a global anti-system movement, as well as its permanent affirmation of the right to be different. This movement, made up of an international network of independent artists and musicians, not always academics, and whose origin dates back to the first avant-garde of the 20th century, arises from the need to explore new possibilities of music and the arts from the perspective of emerging sensibilities…

In the experimental environment, the cult of the composer, the rules in music and the models of composition norms are mostly rejected. A good number of artists of recognised prestige within experimental music affirm that anyone can be a musician or a composer.

As Llorenç Barber said, the aura of the artist who achieved the privilege of feeling like a diva for having performed music theory and for having the grace to decipher sheet music is over. The era of the non-musicians established a new relationship with existence, with the paradigms of thought, the aesthetic prescriptions and with the role of the creator, of the work, of the listener, of the musician and of the art of this sound world of the twentieth century. Today, the non-musician is an audioperformer, a sound creator, a sound landscape artist or a sound sculptor.

The origins of experimental music are much older than those of rock or electronic music. The first manifestations of anti-musicians could be found in the Intonarumori machines by Luigi Russolo (1913).

Your Podcast, Noise Politics, starts from your research on ways to escape the control of noise and the institutionalisation of silence. How did the idea of creating this podcast come about?

It was a radio space in which I analysed the relationship between sound experimentation and ideological militancy. The texts of the locution are also taken from my writings in The Politics of Noise. Noise as the Ultimate Weapon” (2013). I illustrated it musically with works that are fundamental to me and that are part of this undisciplined “Sonora Noosphere”.

Noise, electronic, experimental, industrial… Subversive music has always existed in a break with religions and official powers, regrouping the marginalised and visionaries. The control of noise and the institutionalisation of silence are conditions of power, for this reason, we will open the doors of the auditoriums to let in the noise of the street, we will finish off the music, we will blaspheme, we will criticise the codes and the networks.

I developed 15 chapters that were broadcast at the beginning of TeslaFM. You can currently listen to them on my website.

Stupor Mundi is the title of your latest and eighth album, in which you juxtapose digital drones with soundscapes. How would you describe the evolution of your work?

I have always been more interested in the process of creating and researching new sounds than in the means used for it. I continue recording and developing my own sound material, with which I later recreate landscapes of dark textures, to which I incorporate elements of industrial music together with monolithic drones and harmonic vocals. My work has evolved towards an even darker sound. In my beginnings, the voices were buried; they were just another texture and lately, especially in the live performances, the voices are more present, more defined and ghostly.

Your album Crónica de un Secuestro was included in the 2020 Top Ten Drone of the prestigious American webzine “A Closer Listen”. What did it mean for you to be included in that list? Why do you think they liked it so much?

For me, it was a great surprise and, of course, a great honour to share a list with established artists such as Phill Niblock -an American minimalist artist, director of Experimental Intermedia, a foundation for avant-garde music based in New York or Jana Winderen -a sound artist who has performed concerts and sound installations all over the world, including the MoMA in New York.

Why did they like it so much? I imagine that, apart from the value of my musical creation, the album reflected very well the current situation we were experiencing. The lockdown was a historic moment, I managed to convey the feeling of being kidnapped through drones, textures and layers of synthesisers. The record sold out.

Experimental music and sound art seem to be increasingly present in festivals and in art centres that dedicate part of their programming to experimental music. What do you think is the current state of health of this discipline?

I believe that the new generations have very easily understood this language, which is not new and originates in the first avant-garde of the 20th century. The new listeners and creators claim it as a necessary form of sound creation and an alternative to academicism. This has been partly thanks to the democratisation of creation tools.

Since the 1960s, there have been sound artists and experimental creators working outside of commercial settings and institutions; they have never been on the front page of a newspaper. In any case, it continues to be minority music, understood within more specialized circles or accustomed to ‘rare’ music, which is why it has sometimes been branded as ‘elitist’ as something pejorative.

In Spain, relevant projects have always been carried out -such as the Encuentros in Pamplona, a festival of avant-garde art, concrete and electroacoustic music, performance, experimental cinema and visual poetry, held in Navarra in 1972-, what happens is that in these moments of digital interconnection, it is easier to be in contact with the spheres to which we belong and everything is much more visible.

What’s your chief enemy of creativity?

An alienating job that prevents you from having free time to inspire yourself and develop your creativity. An artistic professionalisation is necessary that allows us to dedicate ourselves exclusively to creation.

You couldn’t live without…

Visual or sound creation evolves in parallel to my life, it is inseparable, I could not live without the moments of research, creation and internal journey in my studio, it is what gives meaning to my existence. Well, and some very important people in my family.