Interview by Živa Brglez

When we are thinking about relationships between ourselves and technology, one thing tends to stand out: our dependence on technology. The reason is quite simple. It is felt on very basic, often psychological or cognitive, levels: from anxiety and depression, impatience and a related decrease in attention time-span to memory impairment and even addiction.

Sometimes the worries rise to not-so-rational extents, and people become preoccupied with apocalyptical notions of robots or AI taking over the world. One artist is very fascinated by this dependence and also, furthermore, by the conflicting and contradictory nature of human’s relation to technology: one knows she or he needs it or relies on it, but also one fears it at the same time.

Ziv Ze’ev Cohen is a Chicago-based Israeli artist who believes technology and tools are all part of natural evolution, and, as with any evolution, something is gained, and something else is lost. He is interested in both losing and gaining. He works in the field of multimedia art, and his works manifest through combinations of installation, sculpture, performance, painting, kinetics, light, and sound. Albeit rational, technology through human perceptions often generates senses of wonder and even transcendence and thus takes on a more metaphysical or even magical angle.

Cohen’s interest lies in technology’s influence on humans, on how we perceive ourselves and our surroundings, and the reality itself. His interactive sculpture Bridge (2017) is an attempt to establish a bridge between two worlds, between ours and the virtual world. The participant tries to navigate the sphere in the virtual world by the movement of his or her hands, thus translating and mediating between the two with own bodily movement.

Even the body is not a human prerogative anymore, as Remanence (2018) tries to show. The kinetic light sculpture is a futuristic take on the body. It is a sexless cyborg that has no clearly definable borders since it is depicted with light rather than some material element. On the other hand, a lot of his works use and regard material as material, often in terms of ready-made objects.

A good example would be the performance of The Authenticator (2016), in which the artist disassembled the LCD screen and put in the authenticator a machine that destroyed and manipulated the screen to produce an art object. Addressing Walter Benjamin’s theoretic line from his essay The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, Cohen is posing questions about the auratic value of art by using mass-produced objects and transforming them into “artistic” objects – using not his hands but rather a machine.

In general, humans do have a lot of cognitive advantages over animals. But, our form could slowly become outdated, if not completely obsolete. There is so much more out there than humans can sense, comprehend or imagine. For example, only by letting technology into our lives can we experience infrared light, as Cohen tried with Infrared (2013), or sounds of lower or higher frequencies than the human ear allows, which Cohen depicted in hacked object 20-20k Hz (2016).

But, as Cohen tried to show in his work, the exchange does not mean only cyborg implants or bodies, robots and so on. Another exchange is happening in a bit more hidden but nonetheless impactful way: technology influences the ways we think, perceive, organise, and make decisions.

You are an artist working at the intersection of technology with art. In your work, you reflect on how we perceive reality through technology. For our audience that is not familiar with your work and background, could you tell us a bit about your background, interests and inspirations?

As a kid, I always liked to disassemble electronic toys and reassemble them in a different form or function—like taking a motor from a broken toy car and adding it to a plastic toy boat to make a speed boat. Luckily, my older brother had a soldering iron, and he let me use it from time to time. At a certain point, I had a whole suitcase of salvaged parts.

One of my strongest memories as a kid was when my dad bought our first VCR. It was an AKAI 4 head Video Cassette Recorder. I loved that machine like it was my puppy. I was thrilled about the fact that I could rewatch things or even record things while I was sleeping and watch them later. Looking back, I guess that was my first advanced body extension. I used to physically open VHS and audio tape cassettes and manually edit them; old school cut and paste.

So, growing up with that mentality of using the machine’s interior as well as its exterior was part of my perspective. I always experimented with alternative ways of using a device. I think I had a special connection with machines pretty early, but to be honest, I think all of us do at this point.

Formally, I studied Photography at the Minshar School of Art in Tel Aviv, my school believed in an interdisciplinary exchange between departments, and I found myself building objects, sculptures and installations, moving towards new media works. Today, I realize that my interest in the camera was primarily tied to the nature of the device, which has the potential to enhance individuals and human society at large.

Two years after graduating, I left Tel Aviv to pursue a Master of Arts in technology studies at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. The department became like a second home to me, and it is also where I teach today.

My work is often inspired by scientific phenomena that challenge our natural senses, like the mirage effect, philosophical ideas about human behaviour as culture, and how technology changes us as a society. To be honest, more than anything, I am drawn to machines. I love to watch them move. After visiting robot and automation conventions, I come back to my studio with a notebook full of notes.

In your own words, your artworks “function as experiential platforms through which technology mediates an experience for the viewer in relationship to their body” (in your own words). Could you tell us a bit about all these ideas that came together and what sparked your interest in merging them?

I find beauty in Movement, Light, and Sound in our world and am very curious about why one can feel so attracted to these three capacities(?). I am very intrigued by how our senses transform those behaviours into feelings. I like to physically and conceptually deconstruct the tools we created as mankind and to investigate how those tools function as an extension of our body and mind.

I truly believe that one of the best things I can offer a viewer as an artist is recreating that old feeling of a new technological encounter as a magical event, just like the first Lumière brothers’ film projection: ‘Train Pulling into a Station’ at a French cafe (although I wouldn’t want my audience to run away from the gallery as it happened in that French cafe).

Remanence is one of your latest works. It’s a kinetic light sculpture recently presented at 062 Gallery in Chicago (EEUU); what is the intellectual process behind this work?

Remanence is a mechanical hermaphroditic body that represents a speculative futuristic body. While it challenges the body’s borders, it highlights our relation to machines and the machine as an extension of the body and its borders.

I like to think of it as a futuristic relic that examines the present through a futuristic observation and uses Western cultural and historical aesthetics to challenge the linearity of our experience of time. The idea started while thinking about body borders. The light represents a nonphysical element of a body. The shape of the body sculpture is the combined 3D scanned bodies of my partner, the artist Xinyi Li and myself.

We scanned ourselves with the Eva 3D scanner, then combined our figures in 3D software, then each created different artworks from the result. Remanence is what I formed from this database. Because we are coming from different cultures, different art influences, and backgrounds, its pretty incredible to see Xinyi’s outcome in relation to mine. This feedback between our works helps this project evolve into new forms.

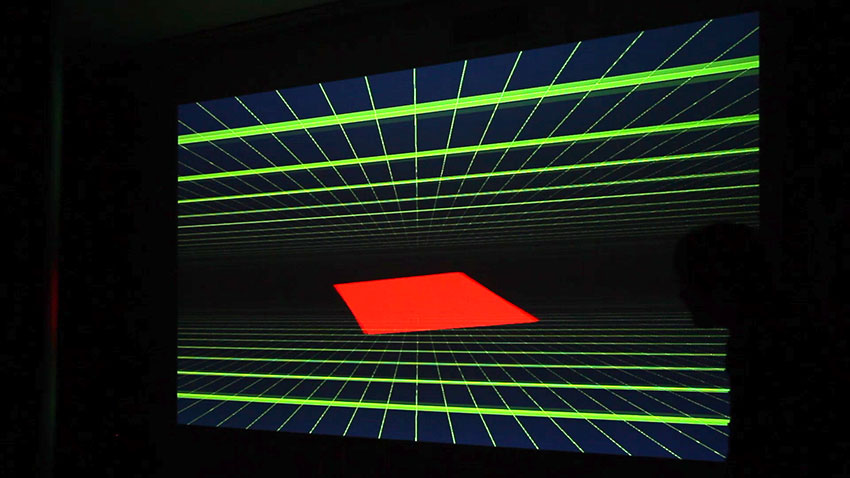

In Cyber Soldier, you perform live, creating sounds and visual effects that blur the fourth wall between the audience and the screen. What reaction did you expect from the people who experienced the performance, and which feedback did you get from them?

To be honest, prior to the show, I just hoped that no one would have an epileptic seizure. I did some testing prior to the show and also projected a trigger warning before my collaborator, Voidpulse, and I played Cyber Soldier. We did try to create a kind of hypnotic feeling through the work. I remember that when we stopped playing, there was an unusual silence before people started chatting.

After the show, we got some very interesting feedback. It sounded like many people experienced a journey through sound and light. In that sense, I feel that for those 16 minutes, we managed to take the viewers into a wormhole experience, diving into different individual dimensions.

Your practice addresses the power struggle between humans and machines, as well as our mistrust and misunderstanding of technology. In your opinion, are we collaborating with machines or are machines collaborating with us?

I think about this collaboration in terms of symbiotic relations: both sides need each other and grow from each other’s successes from an evolutionary perspective. I feel that this is true not only through physical connections like having a smartphone that extends your cognitive and communication abilities but can also take more abstract shapes.

In his mini-series, ‘all watched over by machines of loving grace,’ Adam Curtis shares a theory on how huge human global systems like the financial market were so adjusted to work with computers that countries’ financial actions in the global market were very similar to how computer logic works, in a way, people started making a decision like a calculation machine. So, in a way, I don’t need a bionic transplant to be less human and more machine. The way we think has also changed in direct correlation to how we use technology as a tool of our evolution.

What directions do you see taking your work into?

Recently I feel my works are naturally drawn towards fields of history, representation, and the tools (technology) we use to support them. Religion is something that comes back more and more in that sense. Although I am not religious at all, I was raised Jewish, and the world was explained to me through that lens from a young age; it is definitely something from my personal past.

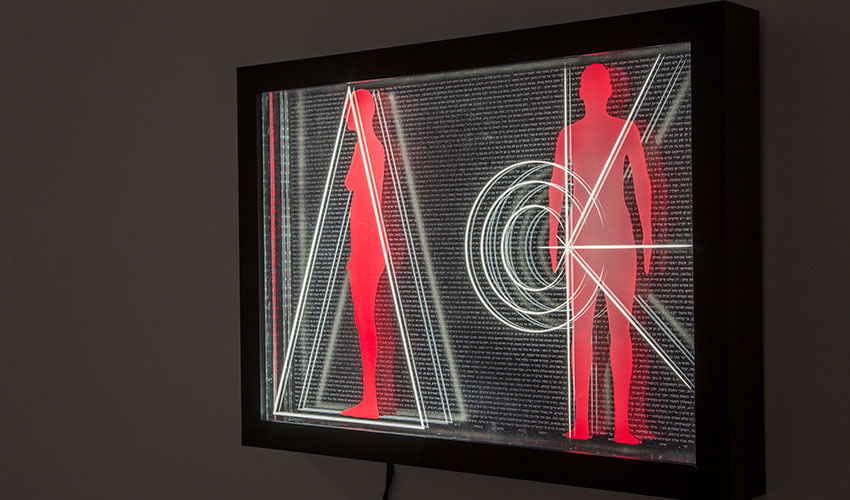

More than that, I am very interested in the relationship between religion and technology. It feels that there is a love-hate necessity there. For example, at 062, at the advice of the curator Duncan Bass, I added a new piece called ‘Manual.’ It is a lightbox collage made with engraved acrylic panels, LED strips and a microcontroller.

This work contains a book from the Kabbalah, (which originated in the 2nd century, ‘The Book of Formation’ (Sefer Yetzirah || ספר יצירה)). Combined with abstract forms, the work represents a keyless manual.

What is your enemy of creativity?

Being still, I need to move; I have to do things. The most intense periods of time in my life were also the ones in which I had lots of new ideas, or I created most of my works.

You couldn’t live without…

Water, food, sleep, and the Web hive brain.