Text by Juliette Wallace

Voice in the Mirror was an exhibition and a unique experiment never before performed, and never repeated since. Now, 5 at years since its staging at LemoArt Gallery (Berlin), as curator of VIM, I recall the distinctive process and findings that resulted from the show.

VIM was an exhibition in two parts: Part I – Albums and Artworks, and Part II – the Synaesthetic Code. Part I involved a blind listening test, whilst Part II depended upon a call and recall scientific investigation, the first of its kind. VIM, put on by my curating organisation, TundoCurating, aimed to find a relationship between visual and sonic art through considering the principles of synaesthesia: a neurological phenomenon in which stimulation of one sensory pathway leads to experiences in a second cognitive pathway (specifically chromesthesia: sound to colour synaesthesia).

Everyone has an element of synesthetic cognition but in 4% of the population, the condition is so acute as to affect their everyday lives (some of these people can’t drive for fear of being distracted by a horrible taste in their mouth at a red traffic light or an irrepressible buzz in their ear at the sight of a road sign).

In VIM: Part I, artists with tendencies to translate sound visually were commissioned to create artworks which responded directly to the music. Five albums from the last five years were assigned to as many artists. The album covers were selected based on their being both painterly and integral to the complete message. Each artist was assigned an album from the selection based on questionnaires.

They were then encouraged to respond visually to the records through a blind listening test in preordained stages. No prior knowledge of the music or album cover was allowed them, ensuring a purely perceptive and personal response to the music.

The resulting pieces, the exact dimensions of a 12’’ LP, were then hung directly across from their corresponding albums in a narrow exhibition space. Mp3 players hung below each commissioned work. In this way, the curious space between image and music was reduced to the size of a room. Both the artists and audience were surprised and delighted to see what paintings had emerged and how they compared to their album counterparts. For the most part, the colour spectrum and the shapes engaged corresponded closely to the LP covers, suggesting that there is a common ground between our sensory perceptions.

Part I was a fascinating insight into the question: ‘what came first, music or image?’ and into the visual power of the sonic. It was a unique moment in the overlap between, not only art, science and music, but also music and marketing, which shed light on the importance of semiotics in our overall perception as determined by neurological pathways. It functioned in the context of the whole, like a dish that had been carefully constructed and served warm, its combined flavours felt and deliberated as a complete dining experience.

Part II, The Synaesthetic Code, worked with the same concept but broke the dish down to its individual ingredients, focusing on elements that then led to the big picture: the deconstruction and subsequent reconstruction of a track. Part II was performed in accordance to strict guidelines laid out beforehand.

The guidelines were as follows:

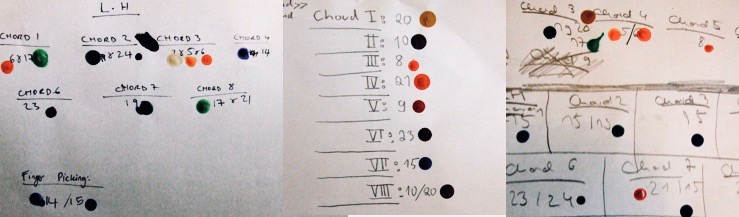

The artists involved are to perform the synaesthetic code act together. They must begin by hearing a recording of the song in its complete form where no immediate response is required of them. They will then be played the pre-recorded deconstruction of the track (out of order) to which they are asked to provide their response on the paper provided. The response is to be according to “chromesthesia” (sound to colour translation). 23 coloured paint tubes will be laid out, numbered from 1-23. The involved parties are to pick between one and three of these colours per chord/note of the deconstructed track, according to what the sound recalls for them. This will then be translated into a painting where long notes are represented in long or thick lines and short notes as dots or dashes.

There were three subjects of the experiment: myself, a curator, writer and musician, Steffi Tränkner, a doctor in psychology, and Chris Snury, a major in environmental engineering and a musician. A song was selected and then listened to in its entirety. When listening to the song in full, although formally we weren’t required to give an opinion, I asked what colours the people around the table saw.

The responses were mostly on the darker end of the spectrum, consisting of main blacks, dark blues and dark grey/slate colours. We then listened to the deconstructed version of the song (one note or chord at a time).

In accordance with the guidelines, we picked colours for each note and jotted them down. Strangely for me, this produced a rather different result than when I was dealing with the complete track. Rather than dark blues and purples, I picked more light greens and browns, even with the occasional bright orange. A similar thing was happening with Steffi, who seemed also to be allowing her emotional, primal reaction to override her previous reception of the song in its totality. Chris Snury on the other hand, was choosing colours that formed a coherent colour palette and related closely to those we had spoken of before. I was curious as to what this meant in relation to neurological compartmentalisation and male/female preceptive powers.

Upon reflection and after having performed a series of synaesthesia related listening tests, I would venture a suggestion that this has to do with male vs. female tendencies and brain-makeup (two things that are related but not the same). I put this into the broader context of ‘neuroscience of sex differences’ i.e. the study of characteristics that separate the male and female brain, as well as society standards.

This difference in application of a brain’s properties (i.e. the function of common elements) along with hormones and a wider societal context results in a divergence of female/male behaviour and information recall.

Neuroscientists are – perhaps rightly – hesitant to confirm absolute distinctions between male and female brains, also for fear of neurosexism, but non-neurological experts in male and female actions (i.e. behavioural experts such as, famously, author, Mark Gungor) have proposed that men and women approach the storing of information differently. The suggestion is that men put information into metaphorical boxes, whilst women treat information as inherently linked.

I also experienced this pattern in the tests I performed for VIM. It appeared that men who partook in the experiments tended to be more literal in their way of thinking, creating a form of grid in their mind and picking real-life situations that sounds to relate to, whereas women seemed to access a more broad-spanning, primal space in their brains and nerves.

As a result, most of the men who I asked to participate gave me responses along the lines of, at the least interpretative end of the spectrum:

I could see the guitar that was being played, I could also see a drum kit” and at the more creative end: “a group of people are walking through a desert, the sun is starting to set. They keep walking along”. Women on the other hand, for the most part, have tended to answer in terms of colours and shapes or even personal sensations such as “ts a dark spiral and there’s a lot of energy and fear” or perhaps “a cotton candy dream where the man dreaming sees only pink and he doesn’t want to wake up.

Whilst it would be unfair, and inaccurate, to take my research as fact as my sample pool is far too small, I nonetheless think that it has brought up fascinating differences between male and female brain usage. Interestingly synaesthesia has also been associated with sexuality, specifically OS (objectum sexuality) i.e. romantic and/or sexual feelings towards inanimate objects. In a recent paper published in December of 2019, psychologists Julia Simner and James E. A. Hughs and neuroscientist, Noam Sagiv, ran experiments that suggested that those who identified as OS also had high rates of synaesthesia [1]. Perhaps a VIM II could be in the making…