Words by Meritxell Rosell

Thinking about who is at the forefront of exploring the nature and potentiality of sound and sensory spaces and Robert Henke is one of the names to pop up first. The German artist and software engineer has been digging deep into what are the limits of sound and space using high-power laser beams in startling audiovisual installations and performances.

Henke’s name is immediately associated with Monolake and Ableton Live too. Two of his creative endeavours have turned out to be fundamental in recent developments in electronic music. With Monolake, his long-term musical project founded along with Gerhard Behles in 1995, he’s been promoting a forward-thinking sound that became central in the club culture that was emerging in Berlin after the fall of the Wall.

Henke is also one of the principal creators of the music software Ableton Live, which has become a standard instrument for electronic music production and a tool that profoundly changed the way producers record and perform.

With a strong engineering background, he’s been fascinated since a young age with science and technology and its intersection with art: There’s so much beauty in engineering and so much craftsmanship in art– in his own words.

This has brought him to develop personal creative tools (algorithms, instruments…) which have become central to his creative process. Already in 2003, Monolake published a track called CERN in their Momentum album, named after the Conseil Européenne pour la Recherche Nucleaire. It’s a high-powered clanging tune that emanates the energetic nature of the collider.

Also a lecturer and researcher in sound and creative computing (he’s held positions at Berlin University of Arts and Stanford), his shows and installations, presented in such renowned institutions like Tate Modern in London and Centre Pompidou in Paris, are a thrilling experience.

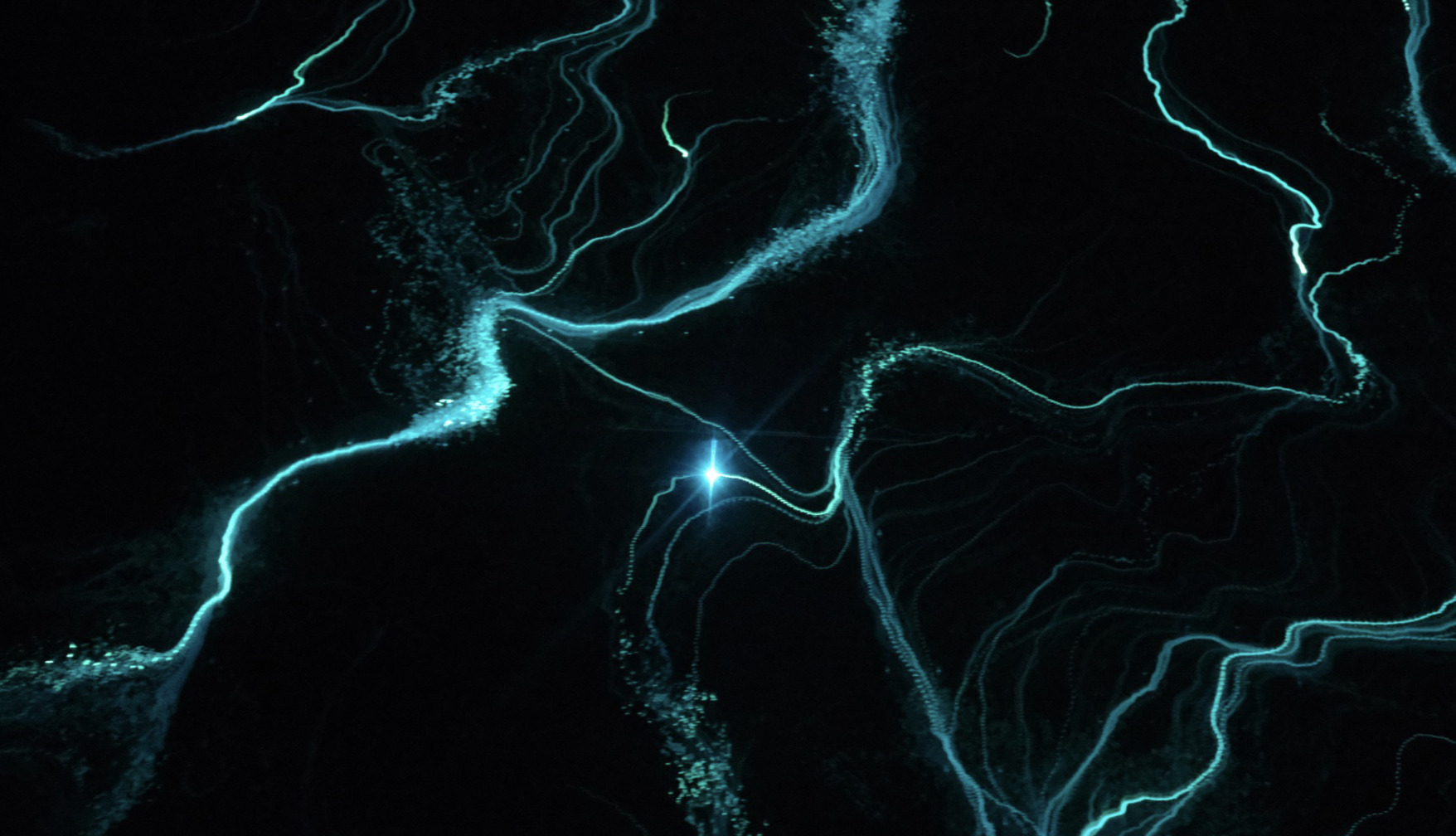

These projects, such as Destruction Observation Field, Lumière II, Werk III, and Deep Web, are some examples of where all his intellectual and empirical universes collide into the most elegant and harmonic materializations.

With them, he creates large immersive experiences taking up dazzling spaces, exploring concepts like coding syntax, meaning and the connections between sound and vision. In his new 8032 Series (still in development), he’s researching abstracting to simpler forms using obsolete technology from the early 80s.

Always pushing research on his work a step further, Robert Henke is setting the grounds for new disciplines that aim to blur boundaries of perception, orchestrating complex algorithmic compositions that trick our senses with a feast of sound and light.

Your work involves sound, kinetic lights, lasers, computing, and programming…. When and how did the fascination with them come about?

That’s an old one. I come from an engineering background family-wise, and I also, from a very early age became interested in the arts, especially more abstract sculptural works of the 20th century and media art, early computer graphics, and so on. I also discovered electronic music.

Thus, my influences did range from Jean Michel Jarre, Manfred Mohr, John Chowning, James Turrell, György Ligeti, Peter Vogel, Nam June Paik, to Mies van der Rohe and Buckminster Fuller.

When I grew older, I began to understand that my fascination for technology and for art can form a fruitful connection. That I was focused on computer-generated music as my main occupation for a long time, mainly due to the unique situation in Berlin that allowed me to become part of the emerging club music culture. Working more in the field of light and installation is actually, for me personally, more of a return to things I did as a teenager…

What are your aims as a sound artist working between technology and art?

I want to touch people with what I am doing. I want that the result transcends beyond a technical achievement. In fact, I consider it most successful when the result is so strong that questions about the technical side become secondary, but people discuss what kind of impact the work had on them mentally.

If that happens, I know that I did a few things right. If other technically more informed spectators start wondering about the underlying infrastructure and the technical concepts, that’s fine, and I am happy to explain them, but I don’t want to rely on technical innovation in my work that much. Since the innovation of today is the standard of tomorrow, work which do not point beyond that does not age very well.

You are also a lecturer and often engage in workshops and talks; what are your conceptual/intellectual research interests at the moment?

Language and form. I spend a lot of time coding, and I spend an equal amount of time trying to make sense of my audiovisual vocabulary. Both are in many ways connected; there are topics of elegance, simplicity, and structure.

Especially when working with lasers, which have many limitations due to the nature of the medium, I am forced to clearly form an abstract idea and execute it in an elegant way. That demands thinking in larger contexts. Drawing a nice shape and creating a sound is easy.

Making sense of that all for a show of one-hour duration is a very different task, and that’s where I actually still want to push myself much further in the future.

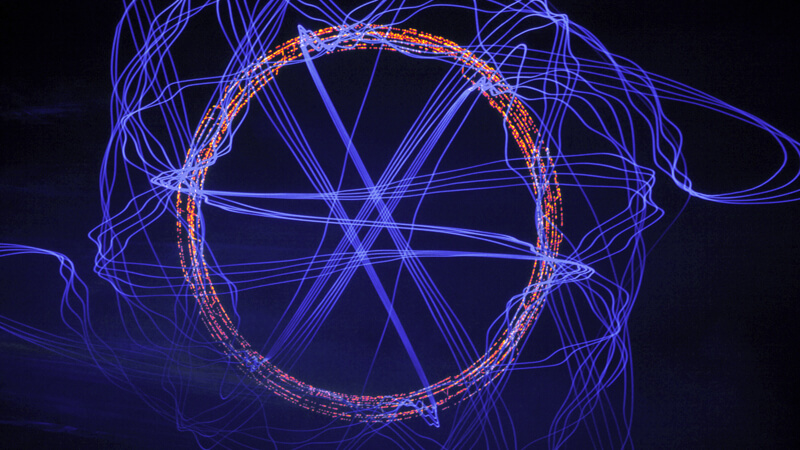

Your latest project, Deep Web, which you premiered at CTM Berlin 2016, is a jaw-dropping installation that uses 12 high-precision lasers and a matrix of 200 moving balloons. What were the biggest challenges you faced in its development?

I am in a happy position that this project is a collaboration with Christopher Bauder, who initiated it, and who’s contributing the technology used to drive the moving balls, and Michael Sollinger, whose amazing laser systems he pushed to the absolute limit to make it all happen.

The biggest challenge for all of us was to get it to run in a very short period of time. I’d say I never created a more convincing musical score with surround sound and the technical back end to sync the control of the moving balls and the lasers to it in a shorter period of time.

Everyone was working like mad on this project during the last four weeks, and I am still amazed that it all worked out in the end.

There were challenges in every detail, and for some magic reason, it all came together quite smoothly. But there were moments when I really felt I was beyond my limits.

Moments where I simply had to end a working session and go to bed because I did not get anything meaningful done anymore. Moments when I was almost not capable of verbalizing my thoughts anymore because I had difficulties actually talking due to exhaustion.

What directions do you imagine taking your work into?

I am pretty much very happy with the things I do now, and I am interested in improving them. There is still a lot to do for Lumière, my laser-based concert piece. I want to present a new version of it, Lumière III, next year, and I want to find time to work more on new music.

What is your chief enemy of creativity?

Time. The things I do become quite complex. Thus they need time to be done, I need to write a lot of software, and I need to coordinate people. That’s all a bit more effort than sitting in the studio and making songs. I have many ideas which I will most likely never be able to do. But that’s a very, very luxurious problem to have, isn’t it?

You couldn’t live without…

…my partners and friends and without a laptop with Ableton Live and a power plug. Living without some of my vintage hardware synthesizers would also suck, and having access to high-power, high-precision lasers is nice too. I need my plants around me because it is nice to look at something green and alive when writing code, and I guess that’s about it, in all modesty.