Interview by Daniela Silva

Operating in the liminal territory between art, technology, and architecture, Sasha Kojjio constructs sensorial environments where light, sound, and text converge into immersive emotional experiences. His works—part installation, part algorithmic meditation—act as portals into perception itself, asking how meaning, rhythm, and emotion can be translated across media and spatial forms. Moving fluidly between the physical and digital, his practice engages with both the poetics of code and the tactility of light, translating data, language, and movement into dynamic architectural experiences.

Kojjio’s journey began in the late 2000s near the Arctic Circle, where prolonged winter darkness turned light into both subject and medium. His early explorations in light painting—capturing traces of motion with handmade tools and long-exposure photography—laid the foundation for a visual language built on rhythm and temporality. Over time, his fascination with the movement of light evolved into a study of the movement of form and meaning. Calligraphy became a pivotal step, introducing him to the emotional resonance of gesture and the visual texture of language. Eventually, this sensitivity to rhythm and curvature found new expression through generative art and algorithmic design, leading to a hybrid practice that is as conceptual as it is sensorial.

Through his collective media.tribe, Kojjio began creating large-scale audiovisual installations that expand the notion of architecture into an emotional field. Each work is a dialogue between light and structure, an attempt to uncover the latent rhythms embedded in built space. This intersection between the technological and the spatial is where Kojjio’s sensibility as a media artist intersects most closely with architecture—not through construction, but through the orchestration of perception. Whether in gallery environments, projection spaces, or natural landscapes, his works reveal invisible harmonies that resonate at a subconscious level, inviting viewers into a state of heightened awareness.

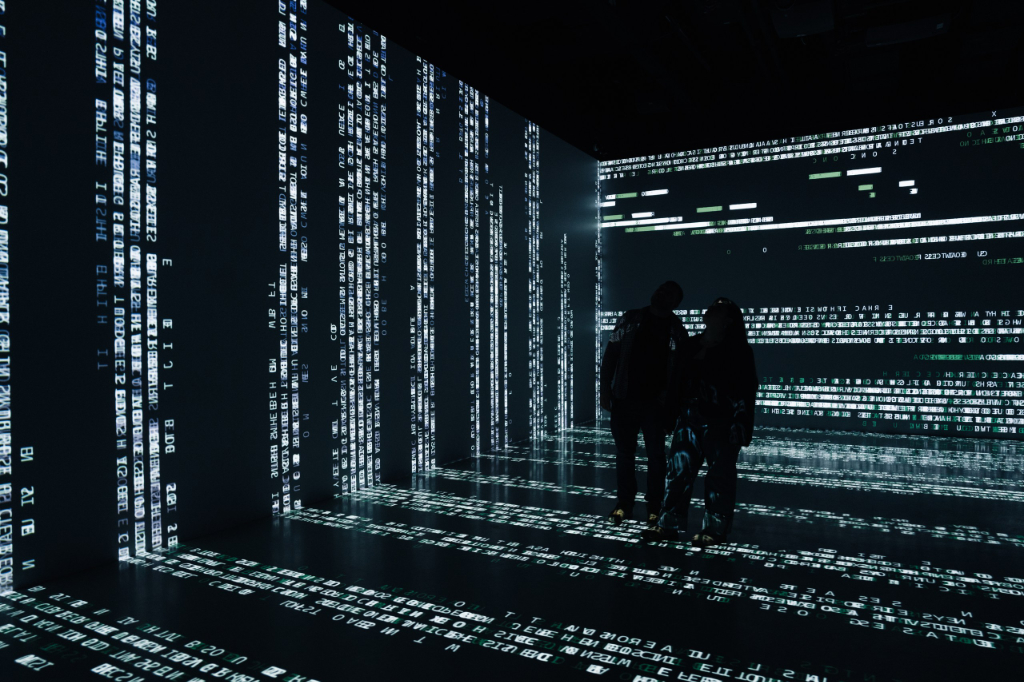

Central to Kojjio’s philosophy is the idea of “psychonavigation” – a form of inner mapping that unfolds through sensory engagement. In an era of digital noise and informational saturation, his installations serve as tools for orientation, guiding both the artist and the viewer through states of mental flux. Works like Semantic Failure 360 translate textual data into fluid architectures of motion, where words lose their linguistic content and instead communicate through rhythm, density, and flow. In this dissolution of language, Kojjio proposes a new mode of understanding—one that operates not through reading but through feeling. With light, sound, and motion, Sasha Kojjio crafts spaces that are not merely seen but experienced – meditative architectures where perception itself becomes a form of navigation.

As artificial intelligence and algorithmic systems increasingly mediate our perception, Kojjio’s work offers a counterpoint: a form of algorithmic intimacy grounded in emotion and imperfection. He humanises code, revealing its poetic potential and reminding us that within the logic of the machine lies a reflection of our own inner architectures.

Sasha Kojjio will present Semantic failure 360 during the Volumens festival in Valencia (Spain) from October 15 to 19, 2025.

Your work lies at the intersection of light, sound, text, and architectural space. How did you first develop an interest in these media hybrids, and how has your approach evolved?

My interest in these media emerged organically, one after another, each becoming a natural continuation of the previous one. Together they formed a kind of personal toolkit — a set of materials and instruments that I use in my practice.

I first started working with light in the late 2000s, in my hometown near the Arctic Circle. During winter, the days were almost entirely dark, and light became a vivid contrast to the surrounding space. I was doing light painting – photography of moving light sources with prolonged exposure- and built my own tools from whatever I could find, including flashlights, LED strips, and incandescent bulbs, to create abstract forms with them.

At some point, I became interested in writing words with light, which led me to calligraphy. I discovered that meaning could be conveyed not only through the content of words, but through their form – how the strokes, rhythm, and curvature influence perception. I practised calligraphy professionally for several years, until in 2017 I discovered media art and generative graphics, which felt like a perfect continuation – shifting focus from letters themselves to what fascinated me in them: rhythm, movement, and form.

Around the same period, we founded media.tribe, where we created audiovisual installations. This deepened my fascination with architecture – I wanted the installations to feel as if they had always belonged to the space, seamlessly integrated into its geometry. I searched for rhythms in structural and decorative elements, for invisible harmonies that could resonate with the viewer.

Working with media.tribe, where I focus on concept, form and light programming, I also saw how sound shapes the viewer’s emotional state – how it can guide perception and reveal new facets of the work. That’s when I began to integrate sound into my solo practice as well, using it to shape atmosphere and tone. Compared to the intense, powerful dynamics of media.tribe, my solo work tends towards the meditative. So, each time I entered a new medium, I had a clear intention. I knew exactly what I wanted to explore, which helped me stay focused and avoid getting lost in technical details that weren’t essential to my artistic process.

Many of your installations explore perception, ambiguity, and what you call “inner psychonavigation” in an era of information overload. How do you define or experience “psychonavigation,” and how does it inform your spatial strategies?

In my personal work, I explore various phenomena – cultural, natural, and digital – and try to reveal them from an unfamiliar angle, uncovering a new layer that viewers may not have seen before. Often, the core of a work emerges from personal experiences I’m going through. I give them a simple visual form and design algorithms that enable the form to evolve in a way that embodies the concept itself. In a sense, my installations become a way to process those experiences – to observe them from another perspective and find balance through them. Viewers often sense that and recognise echoes of their own emotions in the work.

I’ve noticed that people frequently share clips of semantic failure, where fragments of text flow past a standing figure like a waterfall. They caption it with lines like “This is me at 3 a.m. doomscrolling” or “My ADHD brain when I’m trying to argue with a stranger in the comments.” Or with adrift – a piece I created together with my wife and producer, Alisa Davydova, where an algorithm simulates the real-time melting of a glacier. Viewers see not only the changing climate, but also a metaphor for the vanishing present, for the acceleration of time and life itself.

So when I use the term “psychonavigation”, I mean a process of awareness – of sensing and moving through personal or collective states, and working with them through interaction with the installation. It’s both my own navigation while creating the work and the viewer’s navigation while experiencing it.

You have worked in various contexts, including galleries, immersive projection spaces, and even land art. How do the constraints (or possibilities) of each site shape your conceptual decisions? Can a work retain its identity even as you “rework” it for a new space?

I enjoy experimenting with how a work is presented – shifting something that began as video art into projection environments or architectural mapping. For me, the soul of a work lies in its concept – the idea, the essence, the algorithm behind it. Its form can change, its atmosphere can shift, yet the core remains intact. Each new iteration creates a different experience, and as the work evolves, I evolve with it. In a way, my installations trace the path of my own development.

In projection spaces, I can build an entirely controlled environment – a kind of sterile ecosystem where nothing distracts the viewer. I can sculpt the atmosphere, direct the rhythm of perception, and guide the audience through an almost cinematic emotional journey. It’s a rare opportunity to place someone inside the work, to let them feel its pulse from within.

Gallery spaces, on the other hand, introduce a dialogue between the work and the architecture. The physical context and the cultural expectations of the gallery become part of the piece, revealing new layers of meaning. In these cases, I adapt the work to highlight its relationship with the space itself – so that the viewer’s experience is unique to that specific place and moment, something that cannot be repeated elsewhere.

Land art is different – it’s stepping outside the safety of walls, into a territory that doesn’t belong to you. Nature has existed long before you and will continue to exist long after. Therefore, there must be a compelling reason to intervene. For me, land art is about balance — creating something substantial enough to coexist with the landscape without overpowering it, something that integrates and respects the environment while leaving a subtle trace of human intention.

You mention that you operate in the “age of information oversaturation.” As AI, data flows, and machine translation increasingly mediate our experience of texts and imagery, how do you see your practice responding to or intervening in that condition?

Everything in existence strives for balance. When a mass movement starts to lean too far in one direction, I instinctively look toward the opposite – because there’s always a counterforce waiting to pull the pendulum back.

Currently, we are losing the ability to truly understand or comprehend the mechanisms behind algorithms truly. They have turned into a kind of magic – something abstract, distant, almost mystical. In my work, I strive to humanise algorithms, making their inner logic and evolution more visible. I want the viewer to sense what’s happening – whether through intuition or reason— and to recognise the humanity behind the process.

There’s also a lot of meticulous, almost handcrafted detail in my pieces – in the animation, in the micro-movements of light – elements that give the work a soul and emotional depth. I look for those subtle, seemingly illogical moments that nonetheless feel right, because they remind us that imperfection is the most human quality of all.

Talking about Semantic Failure 360, which you are now adapting for Volumens festival. Could you walk us through your process for this work, from the conceptual spark to algorithmic development and site adaptation?

The core idea behind “semantic failure” is that text can carry emotion and meaning not only through the words themselves, but through typography, visual rhythm, and the movement of its structure. I work with large bodies of text, applying sorting algorithms, pattern recognition, and generative systems that shift the focus from linguistic meaning to pure visual and emotional form – to the rhythm, density, and flow of symbols as they dissolve into abstraction.

For its presentation at Volumens Festival, “semantic failure” is reimagined for a projection space, where the walls and floor become active participants in the narrative. I treat these surfaces not as screens but as a living light sculpture that surrounds the audience. Streams of text, typographic connections, and shifting lines create a fluid architecture. This space evolves and unfolds until it reaches a state of emotional release, almost like a digital catharsis.

In Semantic Failure 360, you shift the focus “from semantic meaning to visual forms and emotions.” How do you treat text as a visual element? Do you think of it more as form, as noise, or as something else in this work?

In this work, I approach text from many different angles, applying a series of algorithms one after another – almost like studying it under shifting lenses. Each stage reveals a new aesthetic aspect of language, words, and letters.

At first, the piece begins with texture – the viewer doesn’t immediately realise that what they see is text. Then the algorithm starts searching for patterns, such as repeated letters within words or words within sentences. These repetitions are visualised as lines, forming a constantly evolving architecture – a kind of logical structure in motion. Later, the focus shifts to the visual shape of the letters themselves, as well as the rhythm within words and how it affects perception. I stretch letters, turning sentences into barcodes – another form of reading and decoding meaning.

In the final part, I treat the entire body of text as a single structure and apply generative algorithms inspired by natural phenomena. Through changes in speed and motion, new layers of rhythm and visual patterns emerge – revealing the hidden architecture within language itself.

You mention being inspired by travelling through Asian countries and witnessing how unfamiliar scripts evoke a sensory reading by consciousness. Could you elaborate on that experience and how it shaped your thinking for Semantic Failure 360?

I spent about two and a half years living across different Asian countries, each with its own language and alphabet. When I first encountered unfamiliar scripts, I didn’t perceive them through the lens of typography but rather as pure visual forms. I would imagine how these symbols came into being – what inspired their shapes, how they might connect to local nature, rhythm, or culture.

At some point, I noticed that I could begin to feel the meaning of certain symbols without actually knowing the alphabet – at least on a fundamental, intuitive level. It reminded me of my time practising calligraphy, when writing the same word in different styles could completely change its emotional resonance.

That realisation fascinated me – that emotion and meaning could be transmitted through text even when its semantic layer is removed. This became the seed for what would later evolve into “semantic failure” – an exploration of how text can communicate feeling, rhythm, and energy beyond literal understanding.

When audiences visit the installation at Volumens festival, what do you hope they carry with them after they leave? What kinds of questions or sensations do you hope to trigger, and do you see this work as opening a space for reflection or even disorientation?

In my pieces, I lay out all my ideas, observations, and messages for the audience, creating a situation where they can take them and form something uniquely their own. Each viewer comes to their own conclusions, shaped by their personal perspective and experience. The work has a theme and a conceptual direction, but its interpretation ultimately depends on the audience. I like to think of my installations as immersive spaces for reflection on a particular topic, and I try not to impose a specific point of view.

What’s your chief enemy of creativity?

Overthinking.

You couldn’t live without…

Syrniki.