Text by Tamar Torrance

From the outset, Gill Gatfield’s Habeas Corpus casts the body as arbiter and object: both the first point of contact and contested locus of control. Referencing the Latin legal writ – meaning literally “you have the body” – the project’s name is double-edged, invoking the structures that safeguard individual freedom from arbitrary detention, but also those that strip it away. It is a declaration, a provocation, and imminent caution.

In the heatwaves of New York, Gatfield shaped a speculative futurism through the expansion of Habeas Corpus while in residence at the NARS Foundation NYC. Respirating as it absorbs sweat, her project – like its legal namesake – requires that ‘the body’ be brought forth, suspending confinement and transforming the living flesh into a forum for resistance. Here, where materiality is enmeshed with minimalism and machine learning, the means of resistance swells, surpassing boundaries and revealing sites where resilience either falters or endures. Exposed, the loci of constraint disintegrate, unmoored amid a delirium of ones and zeros.

This evolving work interrogates interrelated structural elements, each signified through the artworks’ titles: The Room, The Wall, Freehold, CHIP (and its IRL counterparts), and Operating Systems. As access points, Gatfield’s clean aesthetics and distilled titles lure the viewer into entanglement with complexity. Adopting white space as its substance, The Room contains and cultivates the ecosystem of Habeas Corpus.

It is unseen yet ubiquitous – an atmosphere that cloaks its inhabitants, drawing each element into a shared rhythm and holding them in concert. A sense of meta-systems in play intensifies as swathes of stretched woven diapers form the living membrane of The Wall. Bleached and absorbent, its soft depths draw fingers in to caress, probe and parse, complicating the interiority of its receptacle.

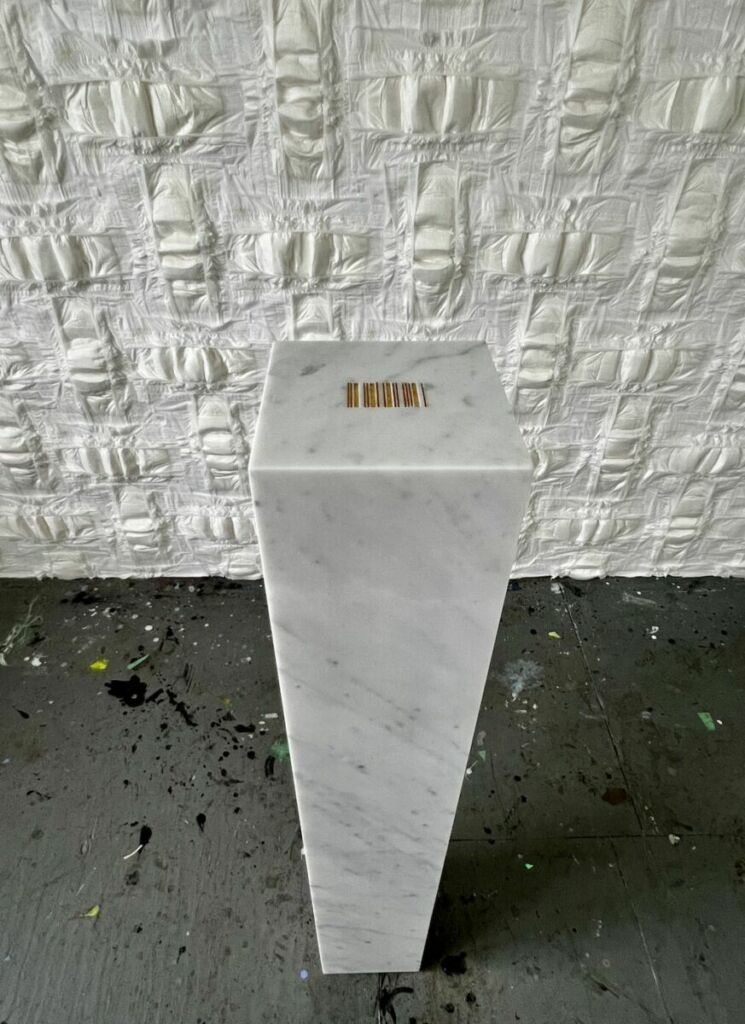

At the end of The Room stands a solitary stone pedestal, its adornment – an AI-infused CHIP – activated through the lens of a viewer’s mobile phone and the artist’s bespoke app. Brought to life by AI and augmented reality (AR), CHIP materialises as a virtual wood carving shaped as ‘I/One’ – a universal form that projects both primacy and infinity. Its anthropomorphic head coalesces with human presence, existing only in relation to the one who summons it, while its totemic shape and ephemeral presence conjure ancestors and perennial spirit figures.

The invisible infrastructure, Gatfield’s Operating Systems, orchestrates Habeas Corpus beyond the reach of ordinary sense perception. Through a dispersed network of multiple grids and codes, the OS silently tethers artworks and ideas to audience, environment, time, and place. Under its governance, static objects reconfigure as responsive systems activated by viewers and shaped by context. Beneath its restraint, minimalism seethes with generative potential – stripped of excess, yet fertile in possibility and permutation.

Together, the artworks form a complex interplay, a site and system where the body’s control/captivity are continually negotiated and redefined. At once container and contained, real and virtual, the body interrogates the structures that govern and define it in the post-human era. Amidst the exchange of energy, atoms, and codes, edges become tenuous, echoing into awareness the fragility of agency co-authored by digital systems. As fixed notions of bodily sovereignty and identity dissolve, new forms of existence rooted in hybridity emerge in their place, underlain by unease.

Habeas Corpus manifests instinctual uncertainties surrounding technology’s hastily expanding influence as a forum to critique the technological innovation to which it remains inextricably linked. It is through this contradiction that Gatfield’s project enacts a speculative futurism; its promise of liberation interwoven with new means of control and existential precarity.

In lieu of catharsis, there is tension: a quiet disavowal of the c’est la guerre attitude that capitulates the imperative to resist. Rejecting surrender as a viable post-human condition, the project insists on resistance, calling forth immersive and participatory states – of suspension, absorption and multiplication – as a conduit to radical agency.

In place of languid compliance – or worse, sublime fatalism – participants are galvanised to interrogate visions of their own humanity both expanded and overshadowed by technology. Habeas Corpus digests this paradox by envisioning a future that denies epistemic rupture. Encoded from a rare ancient wood that predates the last Ice Age, CHIP summons the ancestral past not as a remote memory, but as part of the relational fabric that embeds being in time.

Unlike its counterpart, Avatar returns experience to embodiment; its burnished surface and kauri I-beam, sculpted from the tree’s darker heartwood, is laden with the memory of ages elapsed. In an instant, the idea of the virtual avatar is reversed, reasserting materiality as the true epicentre of becoming. The counterpoint between CHIP and Avatar asks: What now breathes: the human, the machine, or the matter itself?

Relative stages this dialogue across aeons and hemispheres. Its 47,000-year-old kauri figure and Italian marble footing balance Oceanic roots and Mediterranean stone, organic memory and classical reason. Within Habeas Corpus, Relative becomes a meditation on coexistence. Suspended between Minimalism and Futurism, it transforms stillness into an event and the singular “I” into a chorus of bodies, archaic and emergent, through which experience of time is continuously recalibrated.

From the foundations, The Wall calls on deep time, lineage and bloodlines exhumed through its reproductive ties and resistance to entropy – its diaper weave taking 500 years to break down in landfills, worldwide. On the opposing wall, Freehold binds the infinite to the imperial, the domestic to the constitutional. Mounted on Baltic birch plywood and grounded on Lincoln Memorial marble, the vertical plane of woven newborn diapers materialises as a living contract where liberty is codified in ownership, labour and control, where freedom is something held and constrained.

Within this evolving field of connection and correspondence, the multiplicity of bodies – diverse, lived embodiments – emerge as agents of mythmaking, de/re-constructing the allegories that determine existence, time and space. Shifting through tension and paradox, Habeas Corpus unfurls an avant-garde realm: an escape hatch into emergent domains where being is fluid, reality mutable, and becoming not only perpetual but imperative.

Far from the abstractions of art theory and philosophy, Habeas Corpus grounds itself in the lived, tangible conditions of how we engage with the world. Our sense of being, constructed by the ways in which the brain processes and integrates sensory information – whether real or digital – becomes a unified experience of body and environment.

We are wired, by nature, to both absorb our surroundings into our being and extend our consciousness outward into the world around us. Amid this interlocking exchange – chiasm to Maurice Merleau-Ponty – world and ‘self’ become inseparable in Gatfield’s project. In turn, a networked existence is realised where a sense of self is actively pressed upon and reshaped by one’s environment, virtual or otherwise.

While mind-body-world continuity offers existential expansion, it also grants external agents influence over perception and experience. Whether the abject tactility of The Wall and Freehold or the visual illusion of AI-AR enhanced interfaces, stimuli that comingle with the body schema can subtly alter or disrupt being, bodily coherence and control. Here, the radical possibility of networked existence mediated by machines is felt since it is imagined, though not without cost. Presenting transformative potential with one hand, Habeas Corpus casts off separation – and with it, autonomy – with the other.

In this interstitial space – between separation and surrender – Gatfield’s work invests the senses and instincts with agency. As cognitive processes extend beyond the brain and body into these technological artefacts and mixed-reality spaces, we are altered, and, if salient enough, the brain changes in response. Our neural circuits are highly adaptive to environmental context: a biological imperative that allows us to learn and evolve.

The more profound or singular an encounter, the more likely it is to alter connections that underlie our thoughts, memories, and behaviours. Habeas Corpus leverages this neuroplastic potential through the expansion of sensory experience and disruption of perceptual norms, laying bare a site of transformation: capable of rewiring neural pathways and reshaping what it means to be, both here and after.